The Classical Free-Reed, Inc.

History of the Free-Reed Instruments in Classical

Music |

|

Part Two: The Japanese shō |

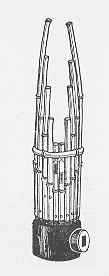

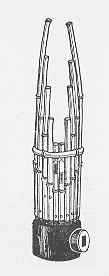

| Illustration 10: Sho.

Image from William P. Malm, Japanese Music and Musical

Instruments,

(Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1959),

99. |

The sho (or shou) is the Japanese equivalent of the Chinese shêng. Although the

standard sho has seventeen pipes and fifteen reeds, there have been

several varieties of the sho at different periods, varying chiefly in the

number of reeds. One is mentioned as having had thirty-six, and others

with twenty-six, nineteen, and thirteen respectively. The sho is perhaps

best known for its use in the Gagaku orchestra, where its principal

function is harmonic.

Gagaku — meaning literally noble or elegant music —

(End note 11)

was founded in 703

A.D. and, as such, is the world's oldest extant music and dance performing

institution. It flowered during the four centuries of the Heian Period (the time between the succession of Emperor

Kanmu in 781, to the beginning of the Kamakura bakufu — samurai government — in 1192), and since that time its

tradition, imperial support,

hereditary personnel and artistic repertory have continued without

interruption. Gagaku is not theatrical dance and music for a popular

audience; it is designed to be performed at a court or shrine, for a

philosophic, moral or religious purpose; for the inthronization of

emperors, for the marriage of crown princes, for the completion of

temples, for the gathering of the first rice.

Gagaku was introduced into Japan by Chinese and Korean musicians in the seventh century. Since its appearance in Japan,

it has been associated with the ceremonies and entertainment of the Imperial Court and its playing tradition has remain

relatively unchanged since 1150 A.D. There is no conductor; the concert master — Gakucho — plays a small

drum (Kakko or Sannnotuzumi) and leads the performance. The Choushi or Awase introduction — musical

passages to confirm the scale for the musical selections which follow — is played first. Each instrument enters in a

particular order: Choushi begins with the sho and Awase begins with a fue.

|

Illustration 11: Sho player performing court banquet music in the T'ang style. (From the Shinzei Kogakuzu).

Image from Robert Garfias, Music of a Thousand Autumns: The Togaku

Style of Japanese Court Music, (Berkeley: University of California

Press, 1975)

To see a

close up view of this image Click Here (117 KB)

|

Robert Garfias wrote about the image at left: "The present Gagaku tradition demands that sho

players hold their instruments with the pipes straight up. The Shinzei

Kogaku Zu illustration depicts either an older Asia mainland style of

playing or simply the artist's fancy."

The present-day Gagaku musicians and dancers are the direct descendants of

the court musicians of the Heian period and many trace their lineage back

for more than one thousand years. These musicians have undergone rigid

training since childhood to master their art; they can perform from modern

Western notation

(End note 12)

as well as from traditional Gagaku notation. The young

court musician completing his ten-year training period is required to have

memorized the entire Togaku repertoire, which numbers ninety-four

compositions. This does not include the netori, choshi, ranjo and special

Bugaku versions of compositions, as well as the entire Komagaku and Shinto

ceremonial repertoire.

| Illustration 12: Gagaku orchestra.

The musicians of the Japanese Imperial Household Music Department performing Kangen, music with winds and strings,

on the dance stage of the Music Department in the palace.

Photo by Robert Garfias, ibid. |

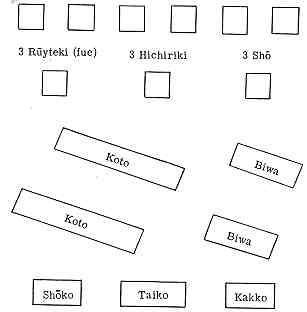

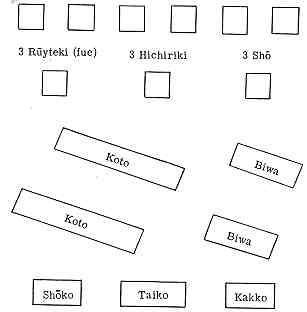

Illustration 13: Seating chart for Gagaku orchestra.

Image from Robert Garfias, ibid. 75.

3 Ruyteki (fue) [flutes], 3 Hichiriki [oboes], 3 Sho [mouth organs]

2

Koto [zithers], 2 Biwa [lutes]

1 Shoko [drum], 1 Taiko [gong], 1 Kakko

[barrel drum]

To see a

close up view of this image Click Here (8 KB)

|

Despite its relatively frozen playing style, Gagaku is not a dead art. New

dances are created today for contemporary occasions, such as the marriage

of Prince Akahito, the Imperial heir. Several Western composers, including

Igor Stravinsky, have shown an interest in Gagaku.

(End note 13)

The current leader of the Reigakusha Gagaku Ensemble, Sukeyasu Shiba, has composed

fifteen works for Gagaku Ensemble — ranging from three to fifty-five

minutes in length — which were recorded on the Columbia record label.

Three of his compositions are titled Hyobyo-no-hibiki I (1986),

Koku (1987) and Shotorashion (1990). He studied Gagaku

in the Gagaku Institute of the Imperial Household Agency. After working as

a court musician for over twenty years (playing the Yokobue), he

became an independent musician and began to disseminate Gagaku both inside

and outside Japan. Sukeyasu reconstructed ancient musical works and

received the Medal with a purple ribbon from the Japanese Government, the

Education Minister's Prize, as well as the Mobile Music Award.

He presently works as a guest professor at Kunitachi College of Music.

The traditional Japanese systems of music notation were types of

tablatures, as were early European systems. They either indicated a

string, a fingering position, or, in the case of the woodwinds, a hole or

fingering. Notation in Japan has always been primarily a supplement to

rote teaching methods and as such is often vague. Indeed, the tradition of

secret pieces and clan-owned music made such a system necessary, however

regrettable it may seem to the contemporary music researcher.

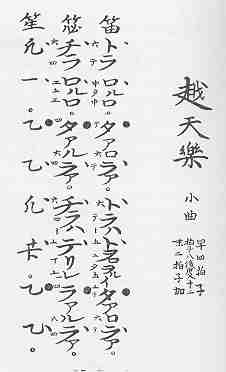

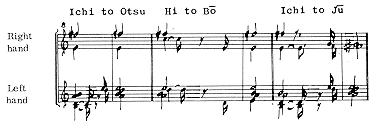

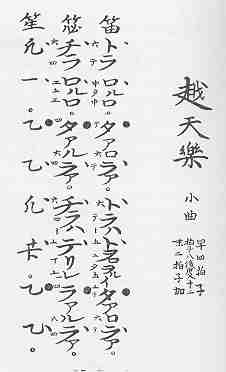

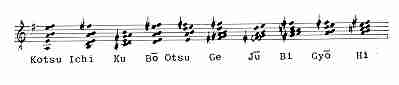

Example 7: Traditional Gagaku Notation.

Image from William P. Malm, op.cit. 264.

|

Example 7 shows the notation of the sho, the hichiriki and the ryuteki for

the beginning of the piece Etenraku. The column at the right is

the flute notation. The second column is the music for hichiriki. The

left-hand column is the notation for the sho. Each symbol represents the

bottom note of one of the eleven chords of the sho, or, in some cases, the

note itself. Rhythm is indicated by dots along the right-hand side of the

column plus white dots among the solfeggio for rests. The large dot

represents beat four or eight, depending on the meter of the composition.

As a rule, Gagaku music is not written in score as shown in example 7.

Instead, each musician has a separate part book. In fact, individual

musicians are sometimes unaware of what is going on in the other

instruments. This is an unfortunate consequence of rote teaching methods.

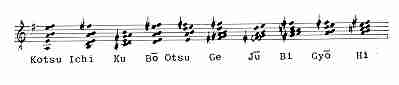

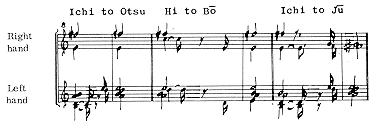

Example 8: The ten aitake.

Transcribed by Robert Garfias. op. cit. 48.

|

The sho players in the Gagaku orchestra most frequently play clusters of

tones, called aitake. Example 8 shows the ten aitake.

The instrument can be sounded either by inhalation or exhalation and the

player is expected to maintain a continuous stream of sound. The

distinctive mark of the professional sho player as opposed to the amateur

is the careful execution of the te-utsuri, the special

changing-patterns for moving from one aitake to another. Since

any one of the aitake may move to any one of nine others, there

are in all ninety possible combinations. The sho player must be familiar

with all the changes. Example 9 shows three examples of te-utsuri.

The effect of the patterns is to give a distinct character to the

connection of any two aitake.

(End note 14)

Example 9: Three examples of te-utsuri.

Transcribed by Robert Garfias. op. cit. 48.

|

The aitake harmonic structures are constructed on the basis of

consecutive fifths. In Gagaku (as in most Asian music) there is no concept

of harmonic progression as there is in Western music. Instead there is one

harmonic structure for each of the tones of the Togaku system.

Example 10, Bato (Yatara-Byoshi), is a transcription of a Togaku

composition. The placing of the various instrumental parts on the score

follows neither the standard Western system, which would place the strings

below the percussion parts, nor the usual Japanese order, which always

begins with the sho, after which come the hichiriki (oboe) and the fue.

The order used here, devised by Robert Garfias (University of California,

Irvine), divides the ensemble into three main instrumental functions: the

primary melody-playing instruments, the fue and hichiriki; the secondary

or supporting instruments: the sho, koto, and biwa (lute); and the

underlying rhythmic foundation supplied by the shoko, kakko, and taiko. In

the sho part, only the aitake have been given; the te-utsuri

patterns, produced by the various combinations of finger movements

when moving from one aitake to another, have been avoided because

they would add great confusion to the score and would overemphasize

subtleties of sho technique at the cost of melodic clarity.

| Illustration 14: Mayumi Miyata

|

One of the foremost sho players today, Mayumi Miyata has premiered works

by John Cage, Toru Takemitsu, Klaus Huber, Maki Ishii and Gerhard Stäbler,

including the world premieres of Cage's work for sho and percussion,

Perugia (1992), Takemitsu's Ceremonial (1992) with the Saito

Kinen Orchestra under the direction of Seiji Ozawa, and Toshio Hosokawa's

Usurohi Nagi (1996) with the Cologne Radio Orchestra. She also

performed at the world premiere of Helmut Lachenmann's opera Das

Mädchen mit den Zündhölzern (1997) at the Hamburg State Opera. Mayumi

(as well as another virtuoso sho player, Ko Ishikawa) has performed with

the Reigakusha Gagaku Ensemble under the direction of Sukeyasu Shiba.

Mark Izu is another performer who specializes in Asian instruments,

including the shêng and the sho. He has studied and performed on the sho

with Japanese Imperial Court master musician, Suenobu Togi, since 1976, and

was the featured soloist for the West coast premiere of Somei Sato's

composition for sho, strings and percussion, Journey Through Sacred

Time, at the 1986 Cabrillo Music Festival. Izu is also a composer of

music for sho, including the live score to Sesue Hayakawaís 1919 film,

Dragon Painter. More recently Mr. Izu was commissioned by Asian

Improv aRts to write and perform a composition for a joint ensemble

featuring Western and Eastern instrumentation called Hibakusha,

Survivors!

Illustration 15: Tamami Tono

Photo by Miro Ito

|

Tamami Tono is another Japanese sho player who is also a distinguished

composer. Her piece for sho and soprano won second prize in the

Sougakudoh Japanese Song Concours, and her works for sho and live

computer were accepted in ICMC98 (Intermational Computer Music Conference)

in the US — ISCM (International Society of Contemporary Music). As a sho

player, she has been playing at the National Theatre of Japan since 1990.

The German composer Gerhard Stä'bler has written for solo sho: Gagaku

— Zwei Stücke der japanischen Hofmusik für Sho (1998) and Palast

des Schweigens — Kassandra-Studie für Sho (1992-3), as well as

Karas. Krähen (1994-5) for sho, contrabass, percussion and tape.

The American composer, John Cage (1912-1992), wrote several pieces for

sho, including One9 (1991) for solo sho, Two3 (1991)

for sho and conch shell/percussion, Two4 (1991) for violin and

piano or sho, and Perugia (1992), for sho and percussion. These

pieces were composed during Cage's most abstract period; he titled

works simply with numbers which represented the number of players in

various ensemble configurations. Most of the works use his "time-bracket

notation" which permitted him to generate pieces rapidly and mechanically.

End Notes

11. Robert Garfias wrote, "Gagaku was introduced to Japan from China and Korea. The Word Gagaku is written

with two Chinese characters that mean "elegant music".

The term is in fact a misnomer, not to imply that this music is not elegant, but only that the term, in Chinese, Ya-Yueh,

refers to the ancient music for the propitiation of the ancestral spirits and the ensuring of the continued balance of

the elements of nature. This was not the music introduced into Japan. The music that the Japanese imported into the

court during the 6th and 7th centuries, was of the type known as yen yueh, or engaku,

The term is in fact a misnomer, not to imply that this music is not elegant, but only that the term, in Chinese, Ya-Yueh,

refers to the ancient music for the propitiation of the ancestral spirits and the ensuring of the continued balance of

the elements of nature. This was not the music introduced into Japan. The music that the Japanese imported into the

court during the 6th and 7th centuries, was of the type known as yen yueh, or engaku,

in Japanese, meaning court banquet music. Ya-yueh, proper, sometimes called Confucian Ceremonial music, was never

introduced into Japan, perhaps because the Japanese already had their own sacred ritual music, kagura, which was

associated with the way of the gods, or Shintoism. Nevertheless, the term, Gagaku, or ya-yueh in Chinese, was retained

by the Japanese perhaps because of the loftier associations carried by that word."

in Japanese, meaning court banquet music. Ya-yueh, proper, sometimes called Confucian Ceremonial music, was never

introduced into Japan, perhaps because the Japanese already had their own sacred ritual music, kagura, which was

associated with the way of the gods, or Shintoism. Nevertheless, the term, Gagaku, or ya-yueh in Chinese, was retained

by the Japanese perhaps because of the loftier associations carried by that word."

Robert Garfias.

12. For over one thousand years, the Gagaku musicians performed only Japanese music learned by rote.

In 1872 a crisis occurred: the Imperial Family decided that Japan needed a European classical orchestra to welcome

foreign guests. The Imperial Household Agency ordered the Gagaku musicians to organize a classical orchestra, but

they refused and went on strike. This was the first strike in Japan. In time, however, the musicians accepted the

proposal at last and began performing European classical music.

Takeshi Mogi, from http://www.asahi-net.or.jp/~PY6T-MG/jmusic.html.

13. For more information about Gagaku, see:

14. Robert Garfias, Music of a Thousand Autumns: The Togaku

Style of Japanese Court Music (Berkeley: University of California

Press, 1975), 48.

The term is in fact a misnomer, not to imply that this music is not elegant, but only that the term, in Chinese, Ya-Yueh,

refers to the ancient music for the propitiation of the ancestral spirits and the ensuring of the continued balance of

the elements of nature. This was not the music introduced into Japan. The music that the Japanese imported into the

court during the 6th and 7th centuries, was of the type known as yen yueh, or engaku,

The term is in fact a misnomer, not to imply that this music is not elegant, but only that the term, in Chinese, Ya-Yueh,

refers to the ancient music for the propitiation of the ancestral spirits and the ensuring of the continued balance of

the elements of nature. This was not the music introduced into Japan. The music that the Japanese imported into the

court during the 6th and 7th centuries, was of the type known as yen yueh, or engaku,

in Japanese, meaning court banquet music. Ya-yueh, proper, sometimes called Confucian Ceremonial music, was never

introduced into Japan, perhaps because the Japanese already had their own sacred ritual music, kagura, which was

associated with the way of the gods, or Shintoism. Nevertheless, the term, Gagaku, or ya-yueh in Chinese, was retained

by the Japanese perhaps because of the loftier associations carried by that word."

in Japanese, meaning court banquet music. Ya-yueh, proper, sometimes called Confucian Ceremonial music, was never

introduced into Japan, perhaps because the Japanese already had their own sacred ritual music, kagura, which was

associated with the way of the gods, or Shintoism. Nevertheless, the term, Gagaku, or ya-yueh in Chinese, was retained

by the Japanese perhaps because of the loftier associations carried by that word."