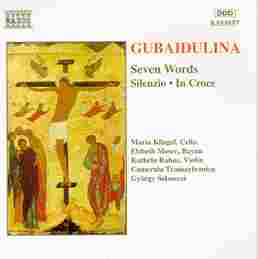

Program:

In Croce, for bayan and cello

Silenzio, for bayan, violin and cello

(All works by Sofia Gubaidulina)

total time: 67'26"

released: 1995

label: NAXOS (8.553557

distributed by MVD Music and Video Distribution GmbH

Oberweg 21-C-Halle V

82008 Unterhaching, Munich

Germany

Review by Steve Mobia

NAXOS is a well produced budget classical CD line. Though the performers might not be well known, their performances are generally fine and well recorded. The pieces selected for recording generally stick to the traditional great masters of the past. What little 20th century music that is offered is not very recent. Things may be changing however with the release of recordings by two contemporary composers - Sofia Gubaidulina and Henryk Gorecki. A recording of Gorecki should come as no surprise since he uses traditional tonality coupled with minimalism to present a sweet melancholy. Gubaidulina however is a brazen avant garde-ist. The choice to include Gubaidulina in the NAXOS catalogue attests to her standing as a major contemporary composer. The disc is also very affordable and should be purchased by any adventurous listener.

Though Gubaidulina has written for full symphony orchestra and many kinds of chamber groups, it is her bayan (Russian button accordion) and string music which NAXOS has chosen to record. Each of the these pieces is an outstanding example of how the bayan can seemlessly blend with strings. The Transsylvanian string players do an outstanding job here. Elsbeth Moser, the Swiss Bayan player is excellent. She handles the extreme demands of these pieces with clarity, assurance and dynamism - holding her own in the company of other recorded Gubaidulina interpreters Draugsvoll, Lips and Hussong. In fact, two of the pieces (In Croce and Silenzio) were originally dedicated to Moser by Gubaidulina herself.

The bayan's role in these pieces might be said to symbolize the earthly body or the soul in physical form - it's breathing abilities predominate. The pieces are acknowledged to have religious, particularly Christian content. This is especially apparent in Seven Words where biblical text of Christ's last words on the cross is evoked emotionally in sound. This being said, the music succeeds with or without the programmatic content.

Though certainly not tonal in a traditional sense, Gubaidulina's music creates a sense of tonal center by reiteration of a pitch or a limited range of pitches. The music is generally not contrapuntal and is based on cell-like figures which expand over an extended period, often building in intensity. At the beginning of In Croce or Cross for Bayan and Cello, the bayan repeats what later is heard to be the natural overtone series of a cello string. The motif rises in pitch and loudness to a climax as the cello introduces a powerful ascending theme. Then a symbolic void ensues as silence and delicate exchanges occur between the cello and bayan. The cello has a slow searching pizzicato solo followed by a downward flowing of notes by the bayan as the cello resumes it's ascension theme. The work concludes as the two instruments change places - the cello playing the bayan's opening motif and vice versa.

Silenzio and Seven Words are a series of miniature episodes - some as short as 2 minutes - that evoke distinct otherworldly atmospheres. Silenzio adds a violin to the duo of cello and bayan while Seven Words adds a full string orchestra. The emotional tone of this music is haunting, introspective and somber.

Silenzio begins with a tentative germination of a theme based around D with brief excursions to chromatic neighbor tones. The 5th piece completes and extends this theme. Though there are 5 stated movements, within each movement are many shifting sections - one dovetailing into the other beautifully. Though played softly, the "silence" here is more metaphorical than actual. One might sense the mysterious hidden workings of existence - hidden being equated with silent.

Seven Words is a major work and one which disproves what some feel that contemporary music cannot have direct emotional impact. There is a strong almost primitive power here with it's heavy percussive tone clusters and ethereal string writing. Perhaps it's the metaphysical subtext that gives Gubaidulina's work a needed dimension beyond purely abstract musical construction.

The string section, possibly evoking angelic forces, appears on occasion to hover above the turmoil of Christ's body and spirit which is represented by the pairing of cello and bayan which often play in unison. A gorgeous melodic passage runs throughout the piece, punctuating the various dramatic episodes. Christ's lament "why hast thou forsaken me?" is musically expressed in the disjunction of cello and bayan while the angelic strings are seemingly indifferent. A desperate striving upward is finally met by powerful unison bursts from the strings then a withdrawal into silence. As Christ's body dies (It is accomplished) the bayan gasps in pain with loud tone clusters, it's physical breathing presence accentuated. At the wor's conclusion, a soft shimmering pattern of fast notes is played on the bayan suggesting the transformation of physical death into spiritual rebirth.

If you've yet to acquire aGubaidulina recording, this is a good one to start with. With the exception of the landmark 1978 piece De Profundis, her best bayan writing is included here.

Date: Fri, 25 Sep 1998 17:47:26 EDT

From: Guysqueeze@aol.com

Subject: gubaidulina recording

"A recording of Gorecki should come as no surprise since he uses traditional tonality coupled with minimalism to present a sweet melancholy. Gubaidulina however is a brazen avant garde-ist."

Dear Editor,

I have one very slight quibble with the deeply felt and beautifully written review of Sofia Gubaidulina's recording by Steve Mobia: that is the implication in the above paragraph that music, in order to radical or brazenly "avant garde," must be atonal or at least dissonant.

If we've learned anything from the music of the American experimentalist tradition of Steve Reich, Terry Riley, Phillip Glass, LaMonte Young, Pauline Oliveros et.al., it's that music can be both tonal AND radical.

The radical nature of minimalism is in it's use of time and repetition: at the time of it's first appearance in the mid-60's, it was as radical a break with the music of the past, as the music of Schoenberg, Berg and Webern was when it first appeared. People may forget, or can't imagine, the impact and outrage that were caused by early performances of now-classic pieces such as Terry Riley's "In C" and Steve Reich's "Four Organs," which were compared to "record needles stuck in the groove" or "musical torture."

I would argue that the one true "brazen radical" of the pre-soviet-break-up era was Alfred Schnittke: his use of polystylistic clashes are unlike anything that was going on in that time-and-place, whereas I see Gubaidulina's music as coming directly out of the European avant-garde of the 50's and 60's. Nothing wrong with being out of a tradition, as there are precious few true innovators, and I agree that Gubaidulina is a great talent; I just happen to disagree with Mobia's description of her as being a "brazen radical."

Thanks for the informative review.

Best,

Guy Klucevsek

Author's Reply:

Dear Reader,

Though I listened to much minimalist music from 1975 through l988 or so, I think it has run it's course. Glass, in particular, is vastly vastly overrated (and is not radical in any way). I agree with Frank Zappa when he said minimalism was mainly popular because it was cost effective. That is: orchestras did not need much rehearsal time (they just needed to know how to count repetitions) and larger audiences were pulled in because it so much resembled pop music. What with government grants for the arts drying up, composers are trying to cater to a public raised on pop.

Minimalism generally is not very challenging though it can have an interesting trance-like effect. I find it refreshing that John Adams, before an obvious minimalist is now writing much more interesting complex and dissonant music. The same goes for San Francisco local Paul Dresher.

Though I've been listening to as much contempoarary accordion music as I can find, I've yet to hear anything for accordion as original as Gubaidulina. The closest composer I can think of is also a favorite of mine: George Crumb (though having written for banjo and slide whistle has yet to include accordion in his work). Both evoke strong metaphysical soundscapes quite unlike the saccharin new age music which proports to be "cosmic". I also find both composers to be readily accessible to an intent unbiased listener.

The problem with serial music is that you have to know the technique in order to apprehend what the composer is doing. When minimalist music was radical, it was an extremist reaction to serial music where the system behind it couldn't be heard (particularly the total serial constructions of Boulez and others). In early Glass and Reich compositions, you can hear everything that happens - nothing is hidden.

Now I prefer something a little more subtle than that. I enjoy ambiguity of key and rhythm and like the contrasts of consonance and dissonance. I don't think you can say Gubaidulina and Crumb are completely atonal or completely dissonant for that matter. Both composers are motivated by symbolic ideas that go beyond purely abstract musical form and it seems to be these motivations that aid them in the powerful effect their music has (at least on this listener).

I actually think originality is still very possible. One problem with the post modern strategy is that it thrives on irony and lacks commitment. The styles of others are mixed and matched in sometimes clever ways but there is often a shallowness to it all. Fun is fun, but there still is a place for an art of commitment.

Sincerely,

Steve Mobia

| About The Free-Reed Review |

| Invitation to Contributors / Submission Guidelines |

| Back to The Free-Reed Review Contents

Page |

| Back

to The Classical Free-Reed, Inc. Home Page |