Cast:

theater: City Thetre, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

total time: 1 hour 10 minutes

run: November 23 through December 30, 2001

review date: December 12, 2001

Review by Henry Doktorski:

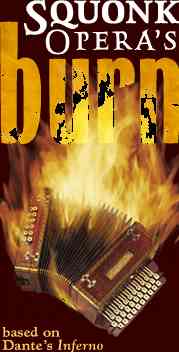

Squonk Opera has done it again. Last year I had the pleasure of seeing their performance at Pittsburgh's O'Reilly Theater and listening to and reviewing their CD Bigsm rg sb rdw nderwerk. Their latest endeavor, an opera titled Burn is no less engaging.Burn caught my attention immediately. It is based on the true story of the town of Centralia in Pennsylvania coal country. The following is the synopsis as printed in the program:

Welcome to Centralia, population 20 and falling. Gone are most of the 1,200 former residents. Gone too, are all but a dozen of the 600+ homes and businesses that made up this former mining town in the anthracite region of northeastern Pennsylvania. Centralia pre-1962 was typical of small-town America, a close-knit community where everyone knew and helped each other. In May 1962, a landfill fire on the outskirts of Centralia ignited an open coal seam, triggering a mine fire that has destroyed the town and the community, and wasted millions of dollars in failed attempts to extinguish the blaze.I loved the performance. The concept is ingenious: a modern-day takeoff on Dante's Inferno. Just as Dante had to pass through nine circles before he reached the center of hell, Squonk Opera's Burn is set in nine scenes, each one titled Circle 1, Circle 2, Circle 3, etc. and each circle gets hotter and hotter until at last the troupe reaches circle 9 where the temperature is "hot as hell." A map of Centralia showing the nine circles surrounding the town is conveniently provided in the program notes.The first bid to put out the fire, which most likely would have succeeded, was $175, but was squelched by bureaucratic red tape. After that, one scheme after another was a day late and a dollar short. Residents fought with each other and the state over what should be done. Officials claimed the fire posed no danger, despite ground temperatures of 750° F, garden vegetables burned to a crisp in the soil, basements so warm that hot water heaters were reportedly unnecessary, dangerously high temperatures of underground gasoline tanks, and homeowners passed out from carbon monoxide. In 1981, the fire became international news, when the earth collapsed beneath a boy playing in his grandmother's yard. The hole, caused by mine subsidence, was reportedly 4 feet wide and 150 feet deep. As he fell, the boy grabbed and clung to the exposed roots of a tree. His cousin pulled him to safety. The heat and noxious gases under the earth's surface were said to have been enough to kill him within minutes.

By 1983, the fire was burning under the center of Centralia proper. Route 61 cracked wide open from the 850° temperatures just a few feet below the road surface. A study concluded that the fire could last for 100 years and total excavation of the burn zone would cost over $660 million, making all earlier options look cheap by comparison. Instead, Centralians voted to accept a $42 million government buy-out of their homes, and the town of Centralia was slated for demolition and taken off the map. Today, a few stubborn hold-outs, mainly elderly, refuse to leave despite the dangers. They theorize that the mine fire has been a vast conspiracy perpetuated by the government to obliterate the borough of Centralia and get its hands on the town's anthracite coal. For all intents and purposes, attempts to extinguish the fire stopped with the federal buy-out.

Legend has it that over 100 years ago, the town priest criticized Centralians who sympathized with the Molly Maguires, Irish coal miners who fought a violent campaign against the mine owners. Afterwards, while praying in the cemetery, he was attacked and beaten. The story goes that in revenge, he uttered a curse from his pulpit upon the town; that day should come when Centralia, founded on a bed of coal, should burn -- in hell -- forever. Today, nearly 40 years after it was ignited, Centralia's inferno burns on.

In this performance, Squonk is headed in a more theatrical direction, as the musicians are now more acting less as musicians and more like actors. The music, in fact, seemed to take a back seat to the acting. I'm not quite sure this is a good direction to take, as I think their acting skills are not quite on the same level as their musical skills. Fortunately, audience interest was stimulated by the prerecorded video recordings which were shown on various screens throughout the theater.

Free-Reed fans will be pleased that Jackie played accordion more throughout this show. It seemed that her accordion (a 72 bass 2-octave piano-accordion designed by Walter Kuhr of New York City's Main Squeeze) shared equal billing with the piano. Jackie's playing was excellent and helped create an atmosphere of despair, as the entire "opera" was focused on a very sad plight: the destruction of the town of Centralia. The play makes you think. And thinking, I believe, is a good thing.

Due to its success, the opera has been extended one week. (It was originally scheduled to close on December 23.) If you are going to be anywhere near Pittsburgh for the rest of this month, I strongly suggest you take the time to see Squonk Opera's Burn.

P. S. Oh, by the way, Jackie doesn't really burn her accordion during the show; in the last scene she simply pulls out a previously-burned dummy button accordion just for kicks.

| About The Free-Reed Review |

| Invitation to Contributors / Submission Guidelines |

| Back to The Free-Reed Review Contents

Page |

| Back

to The Classical Free-Reed, Inc. Home Page |