Very few people can read Gongche notation anymore, even professional

shêng players. Today, shêng players are trained to read modern staff

notation, as well as tablature, which uses numbers and other symbols to

indicate the pitches and rhythms. The following example is a type of

tablature which originally came to China from the West via Japan.

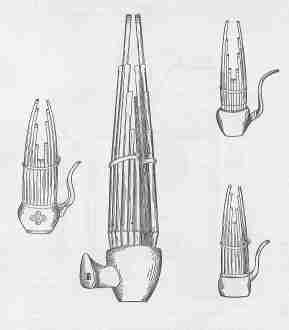

During the second half of the twentieth century, improvements were made to

the shêng. There are now shêngs with 36 and 51 pipes (with keys to extend

the range of the fingers), as well as amplified shêng, alto shêng, bass

shêng and keyboard shêng. There are also chromatic shêngs which allow the

performer to modulate to different keys as well as play complicated chords

and polyphonic passages. The bass shêng, also known as BaoShêng,

is large and heavy and has to be placed on the lap or on the floor. Its

sound is low and mellow and it can produced a great variety of chords.

Steel tubes are used instead of bamboo tubes, for large bamboo tubes that

resonate low pitch notes are difficult to find.

Example 5: Happy Woman Soldiers from the ballet The Women

Soldiers of the Red Army as arranged by Shi Po and Tang Fu for shêng

(early 1975). This ballet was created during the Cultural Revolution and

is very well known in China. This example appeared in the anthology

Best Selection of Shêng: Compositions from 1949 to 1979. It was

compiled by Chinese Musical Associations and published by

People's Music Publishing House in Beijing.

As in the past, the shêng today is still an integral part of the cultural

life of the Chinese people. The modern Chinese orchestra consists of four

sections: woodwind, string, plucked string and percussion. The string

section consists of instruments like the GaoHu, ErHu, ZhongHu and

occasionally, a BanHu. The plucked string section consists of

instruments like the LiuQin, Pipa, Zhong Ruan, Da Ruan and

occasionally, San Xian. In the woodwind section are instruments

like Dizi (Bangdi, Qudi and Xindi), Suona and

Shêng. The percussion section consists of instruments like the

Chinese drums, gongs and timpani. The modern Chinese orchestra uses the

cello and double bass to strengthen the bass composition of the orchestra.

Before the introduction of these Western musical instruments the main bass

string instrument was the GeHu. Other instruments include the

Konghou (harp), Zheng (zither) and Yangqin

(hammered dulcimer).

(End note 8)

Very few shêng players have concertized in the West. Wang Zheng Ting (b.

1955) is a graduate of the Shanghai Conservatory and holds an M.A. degree

in Ethnomusicology from Monash University in Australia. He is the founder

and director of the Australian Chinese Music Ensemble and has actively

promoted Chinese music throughout that country. His 1997 US tour

included both lectures at various universities and the premiere in

Minnesota of his Concerto for Sheng, commissioned by the American

Composers Forum. Wang is presently pursuing the Ph.D. in Ethnomusicology

at the University of Melbourne. I had the pleasure of meeting him and

hearing him perform in 1999 at a

concert

in New York City sponsored by The Center for the Study of Free-Reed

Instruments (Graduate School and University Center of the City

University of New York).

is the same as the pronunciation of another Chinese character "shêng"

(rising). Therefore the instrument implies luck and auspiciousness.

is the same as the pronunciation of another Chinese character "shêng"

(rising). Therefore the instrument implies luck and auspiciousness.