| | Organist | Accordionist | Composer | Conductor | Author | Educator |

|

Henry Doktorski

|

|

October 2001: Henry Doktorski performed with the Duquesne University Contemporary Ensemble on Thursday October 11, 2001 in a performance of Kammermusik No. 1 by the German Neoclassical composer Paul Hindemith (1895-1963). The concert, at the Duquesne University Recital Hall in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was conducted by Jonathan Niederhiser.

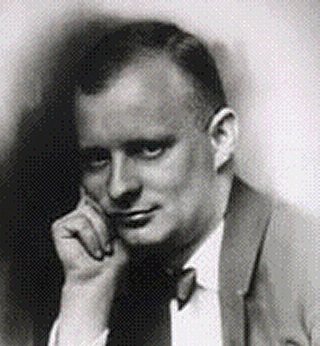

Paul Hindemith The fifteen-minute work -- in four movements -- was scored for a string quintet with flute, clarinet, bassoon, trumpet, accordion, piano and a battery of percussion, including xylophone, a siren and a tin can filled with sand. It was written in 1921 and was the first of seven Kammermusik pieces -- literally "Chamber Music" -- which have been called "A twentieth-century equivalent of J. S. Bach's Brandenburg Concertos."

One of the main innovators of musical modernism, Hindemith was a composer, conductor, violist, educator, and theoretician. Of the four founders of modernism -- Arnold Schoenberg, Igor Stravinsky, Bela Bartok, and Hindemith -- one can argue that Hindemith was by far the most scholarly and intellectual in temperament. His theoretic interests were both deep and wide-ranging and included medieval philosophy and the writings of the early church, as well as musical topics. He could play all the standard musical instruments at least passably and was a recognized virtuoso on the viola and viola d'amore. A sought-after educator, he taught such composers as Lukas Foss, Arnold Cooke, Franz Reizenstein, and Norman Dello Joio and wielded great influence in Europe and the United States between the two World Wars.

Kammermusik No. 1 is a cheerful, irreverent suite which manifests clear reference to Hindemith's early experience performing in dance bands and musical comedy orchestras in and around Frankfurt. Strong rhythms, sparkling instrumentation, and incorrigible impudence are the work's distinguishing features. Its first three movements are a boisterously dissonant prelude, a frivolous march, and a pastoral 'quartet' for the three woodwind instruments and a single note on a glockenspiel. The finale unleashes the whole ensemble in an obstreperous display of anarchic humor. The climax comes with the quotation, by the trumpet, of a contemporary fox trot in G major, accompanied by scales in all the other eleven major keys, and the end is a manic stretto worthy of any great comedy of the silent screen.

A concertgoer who attended a performance of Hindemith's Kammermusik No. 1 in Munich in 1923 wrote: "A few weeks earlier I had been involved in a concert by the American George Antheil . . . and witnessed a bombardment of tomatoes, eggs, and even stink bombs. I prepared myself for something similar on Hindemith's first appearance in Bavaria's conservative capitol. And I was right. Scarcely had the last measures of the fox-trot imbedded in the piece subsided than the hall turned into chaos. Whistles blew, boos resounded, chairs flew through the air -- a hellish noise filled the large room. Hindemith, in the meantime, had disappeared backstage with the other musicians. As the spectacle reached its height, he reappeared -- thoroughly calm -- seated himself at the percussion . . . beat with all his might on the drums, and let the slide whistle howl. The honest M nchener were so taken aback by this unexpected behaviour that Hindemith was the victor in an unequal battle."

Doktorski said,

"Hindemith's Kammermusik No. 1 was one of the very first orchestral pieces written by a classical composer to include accordion. Only Tchaikovsky's Orchestral Suite No. 2 (1883), Umberto Giordano's opera Fedora (1898) and Charles Ives Orchestral Set No. 2 (1915) predate it."Nonetheless, it is significant to note that Hindemith's Kammermusik No. 1 was indeed the first piece written by a classical composer for the "chromatic accordion" -- an instrument which can play chromatic tones, i.e., tones in all twelve keys. (The piano accordion is also technically categorized as a "chromatic" instrument.) Tchaikovsky, Giordano and Ives wrote for "diatonic" button instruments which could only play in one key.

"In addition, Hindemith wrote for an advanced instrument which had only recently been manufactured by the Hohner company: an accordion which included both standard stradella left-hand buttons and free-bass left-hand buttons. The primitive diatonic accordion simply would not do for Hindemith's music, which featured modern polytonal harmonies. The evolution of the accordion and the training of its performers had advanced sufficiently in Germany by the early 1920s that Hindemith felt confident that he could find competent classically-trained accordionists to perform his music. The classical accordion had come of age."

Conductor Jonathan Neiderhiser said, "It's really amazing how much the accordion adds to the ensemble in this piece. It's coloring is quite distinctive and memorable. Without the accordion, Kammermusik No. 1 is simply not the same."

Some passages above were quoted from texts by Steve Schwartz, Calum MacDonald and David Neumeyer.

|