| | Organist | Accordionist | Composer | Conductor | Author | Educator |

|

Henry Doktorski

|

|

May 2007: Henry Doktorski performed on accordion with the Carnegie Mellon Philharmonic under the direction of Juan Pablo Izquierdo in performances of Kammermusik No. 1 by Paul Hindemith on Tuesday May 1, 2007 at Carnegie Music Hall in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and again on Thursday May 3 at Severance Hall in Cleveland Ohio.

Carnegie Mellon Philharmonic Program Cover The Philharmonic's program consisted of Hindemith's Symphonic Metamorphosis on Themes of Carl Maria von Weber, Kammermusik Number 1, Five Dances From der Daemon and Symphony Mathis der Maler. Paul Johnston, a faculty member in Carnegie Mellon's School of Music, hosted a pre-concert talk at 7 p.m.

"The orchestral music of Paul Hindemith is a rich legacy of early 20th century creativity and innovation," said Marilyn Taft Thomas, interim head of the School of Music. "Yet his symphonic works are seldom included in mainstream concert programming. This unique all-Hindemith concert, along with a pre-concert talk by Paul Johnston, provides a backdrop for the considerable performance abilities of the Carnegie Mellon Philharmonic and its renowned music director and conductor, Juan Pablo Izquierdo," Thomas said.

Maestro Izquierdo has conducted Chile's National and Philharmonic Orchestra and won first prize in the Dimitri Mitropoulos International Competition for Conductors in 1966. That same year, he was named assistant conductor to Leonard Bernstein of the New York Philharmonic. His international appearances include conducting the Bavarian Radio and BBC orchestras, as well as other radio orchestras in Hamburg, Berlin, Frankfurt, Leipzig, Madrid, Glasgow, Paris and Brussels. He has conducted ensembles around the world, including the Vienna Symphony, the Holland Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, the Dresden Philharmonic, the Jerusalem Symphony and the Israel Chamber Orchestra. "Featuring an all-Hindemith program, the philharmonic will cover a retrospective of different periods of the work of this great master," Izquierdo said.

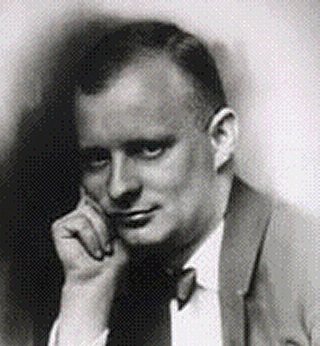

One of the main innovators of musical modernism, the German Neoclassical composer Paul Hindemith (1895-1963) was a composer, conductor, violist, educator, and theoretician. Of the four founders of modernism -- Arnold Sch nberg, Igor Stravinsky, B la Bart k, and Hindemith -- one can argue that Hindemith was by far the most scholarly and intellectual in temperament. His theoretic interests were both deep and wide-ranging and included medieval philosophy and the writings of the early church, as well as musical topics. He could play all the standard musical instruments at least passably and was a recognized virtuoso on the viola and viola d'amore. A sought-after educator, he taught such composers as Lukas Foss, Arnold Cooke, Franz Reizenstein, and Norman Dello Joio and wielded great influence in Europe and the United States between the two World Wars.

Paul Hindemith Regarding Hindemith's Kammermusik No. 1: The fifteen-minute work -- in four movements -- is scored for a string quintet with flute, clarinet, bassoon, trumpet, accordion, piano and a battery of percussion, including xylophone, a siren and a tin can filled with sand. It was written in 1921 and was the first of seven Kammermusik pieces -- literally "Chamber Music" -- which have been called "A twentieth-century equivalent of J. S. Bach's Brandenburg Concertos."

Kammermusik No. 1 is a cheerful, irreverent suite which manifests clear reference to Hindemith's early experience performing in dance bands and musical comedy orchestras in and around Frankfurt. Strong rhythms, sparkling instrumentation, and incorrigible impudence are the work's distinguishing features. Its first three movements are a boisterously dissonant prelude, a frivolous march, and a pastoral 'quartet' for the three woodwind instruments and a single note on a glockenspiel. The finale unleashes the whole ensemble in an obstreperous display of anarchic humor. The climax comes with the quotation, by the trumpet, of a contemporary fox trot in G major, accompanied by scales in all the other eleven major keys, and the end is a manic stretto worthy of any great comedy of the silent screen.

A concertgoer who attended a performance of Hindemith's Kammermusik No. 1 in Munich in 1923 wrote: "A few weeks earlier I had been involved in a concert by the American George Antheil . . . and witnessed a bombardment of tomatoes, eggs, and even stink bombs. I prepared myself for something similar on Hindemith's first appearance in Bavaria's conservative capitol. And I was right. Scarcely had the last measures of the fox-trot imbedded in the piece subsided than the hall turned into chaos. Whistles blew, boos resounded, chairs flew through the air -- a hellish noise filled the large room. Hindemith, in the meantime, had disappeared backstage with the other musicians. As the spectacle reached its height, he reappeared -- thoroughly calm -- seated himself at the percussion . . . beat with all his might on the drums, and let the slide whistle howl. The honest M nchener were so taken aback by this unexpected behaviour that Hindemith was the victor in an unequal battle."

Hindemith was surprised about the vehement reception which Kammermusik No. 1 received, and sixteen years later commented about it (and the overwhelming preponderance of old women in the audience during a recent American performance) in a letter to his wife dated March 3, 1938:

"Rehearsals occupied the whole morning. I began with the 'Dances,' which went very nicely from the start. Then we rehearsed 'Der Schwanendreher' thoroughly; the orchestra still remembered it quite well from last year, and Lange did his stuff respectably too. To end with, after Mozart's E-flat Major Symphony, they rehearsed that ancient old Kammermusik of mine with the siren. One wonders why people made such a fuss about his piece at the time. It is not at all badly written, and there is nothing, apart from a few harmonic and melodic teething troubles, to upset innocent souls. It is not exactly refined, and the extravagant use of percussion, etc., was certainly a concession to the prevailing (lack of) taste at that time. But, good Lord, one only needs to look at all the crap that is being produced today in this chemically pure cultural atmosphere of ours, to realize how thousand times worse in regard to technique, invention, musicality, and even character it all is, compared with this not very important piece. And someone who is bothered by a siren would find much wider scope for his indignation in wind machines and bleating sheep. People here [in America] are not so malicious. In the evening the piece was a great success (rightly so, for the performance was very good)--in spite of, or because of, the elderly female population from which concert audiences are recruited here as in all other American cities (in which connection it is open to doubt whether it is permissable to bring together two such differing conceptions as recruits and dolled-up crones). They probably felt themselves transported back to youthful times of unfulfilled desires: when the siren shrieked one could literally hear the rusted bones rattling. I played like an old violist who had gone through many fires unscathed, and the dances also went very well. Huge applause."Doktorski explained that the accordion was not included in the orchestration until 1952, thirty years after the premier:"In 1922 when Kammermusik No. 1 was first performed, the accordion did not appear in the orchestration; the work was originally scored with harmonium. The harmonium was a popular instrument in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Many classical composers wrote music for the harmonium, including: Hector Berlioz, Carl Maria von Weber, Franz Liszt, Camille Saint-Sa ns, Charles Gounod, C sar Franck, Gioacchino Rossini, Bedrich Smetana, Leos Jan cek, Anton Dvor k, Max Reger, Sigfrid Karg-Elert, Richard Strauss, and several of Hindemith's contemporaries, such as Arnold Sch nberg, Kurt Weill, Arthur Honegger and Dmitri Shostakovich.This is the fourth and fifth times Doktorski has performed Hindemith's Kammermusik No. 1: first in 1995 with the Pittsburgh New Music Ensemble, second in 2001 with the Duquesne University Contemporary Ensemble, and third in 2003 with the Carnegie Mellon University Contemporary Ensemble."However, by the mid-twentieth century the harmonium had lost so much popularity and become so scarce that Hindemith had to rewrite the part for accordion, an instrument at the peak of its popularity. The composer explained: 'Kammermusik has a part for a harmonium of a kind that no longer exists. I have rewritten it for an accordion. . . With it the piece will be easier to perform.' (from a letter to Hindemith's publisher Willy Strecker-- one of the directors of Schott s S hne in Mainz--dated November 28, 1952.)"

Some passages above were quoted from texts by Steve Schwartz, Calum MacDonald and David Neumeyer.

|