| | Organist | Accordionist | Composer | Conductor | Author | Educator |

|

Henry Doktorski

|

|

February 2008: Henry Doktorski performed with the Pittsburgh Opera Theater Orchestra in four performances of Kurt Weill's Lost in the Stars at the Byham Theater in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Program Cover This dramatic and thought-provoking musical theater tragedy in two acts was written in 1949 with music by Kurt Weill, and book and lyrics by Maxwell Anderson based on the novel Cry, the Beloved Country by Alan Paton. Set in apartheid-era South Africa, it tells the story of Absalom, the son of a Negro village preacher, who accidentally murders a white man in a desperate bid to provide for his wife and child. Arrested and condemned to hang he is visited by his father, who departs in despair. Before his son is executed, the murdered man's father comes to the preacher to offer compassion and understanding instead of hatred and retaliation.

Kurt Weill (1900-1950) was a leading German-American composer of music theater and concert pieces. His best-known work is The Threepenny Opera, which contains his most famous song: "Mack the Knife." He used the accordion (and sometimes the bandone n) in five works: Mahagonny, The Threepenny Opera, Happy End, Marie Galante, and Lost in the Stars.

Lost in the Stars opened on Broadway at the Music Box Theatre on October 20, 1949 and closed on July 1, 1950 after 273 performances. Weill used African American musical idioms including negro spiritual melodies, blues and jazz to help create a suitable atmosphere. The chorus numbers are especially spectacular. The orchestration is scored for: 2 violas, 2 celli, double bass, flute, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 alto saxophones, tenor saxophone, oboe, English horn, trumpet, harp, percussion, piano and accordion.

Lost in the Stars was Weill's last Broadway musical play: he died in New York City less than a year after its premi re, on April 3, 1950. With Lost in the Stars Weill's career in the theatre had come full circle. He had begun his career in Germany by making opera into popular music; and he had ended his career in America by succeeding in making popular music into opera.

This production of Lost in the Stars by the Pittsburgh Opera Theater was directed by Jonathan Eaton and conducted by the legendary opera conductor Julius Rudel. Maestro Rudel, born in 1921 in Vienna, Austria, emigrated to the United States in 1938 at the age of 17 just as the Nazi army invaded his homeland and, after studying at the Mannes College of Music in New York City, established himself in America as a conductor of note. Among his more prestigious positions were his appointments as music director for the New York City Opera (from 1944 to 1979), and the Buffalo Philharmonic.

Assistant conductor and pianist Robert Frankenberry, conductor emeritus Julius Rudel, and accordionist Henry Doktorski

pose backstage between acts for the photographer.Maestro Rudel has won a Grammy Award and seven Grammy Nominations. His many opera recordings include Massenet's Manon and Cendrillon, Boito's Mefistofele, Verdi's Rigoletto, Bellini's I puritani, Weill's Silverlake, Ginastera's Bomarzo, and Handel's Giulio Cesare which won the Schwann Award for Best Opera Recording. Maestro Rudel was made a Chevalier des Arts et Lettres by France and has been decorated by the governments of Austria, Germany, and Israel. Moreover, he has received a variety of honorary doctorates from universities and colleges in the United States.

Maestro Rudel first conducted Lost in the Stars fifty years ago (in 1958) with the New York City Opera. He later recorded the work in 1993 with the Orchestra of St. Lukes and the Concert Chorale of New York. He explained, "Lost in the Stars is a powerful piece. In fact, I must confess that I can never look on stage during the last scene of the opera because I break up if I do."

Maestro Rudel also explained one reason why Kurt Weill might have chosen to use the accordion in the orchestra: "The accordion is one of the instruments in Kurt Weill's palette, in his repertoire, as a composer. He sometimes uses it to evoke the sound of a German jazz band of the 1920s; the type of music the young Kurt Weill often heard in his native country, where the instrument was undoubtedly very popular."

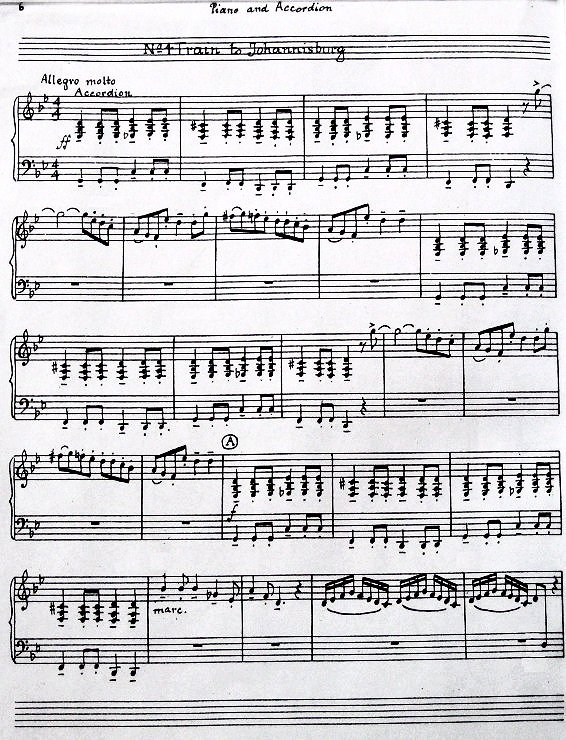

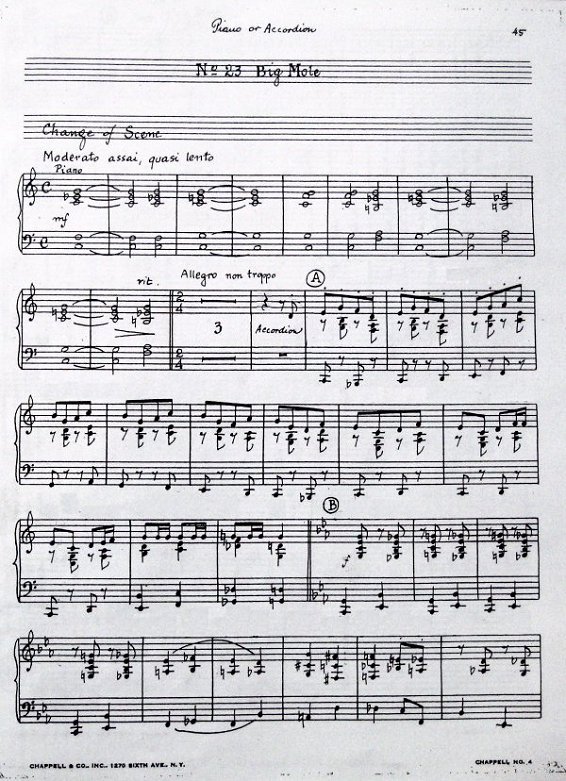

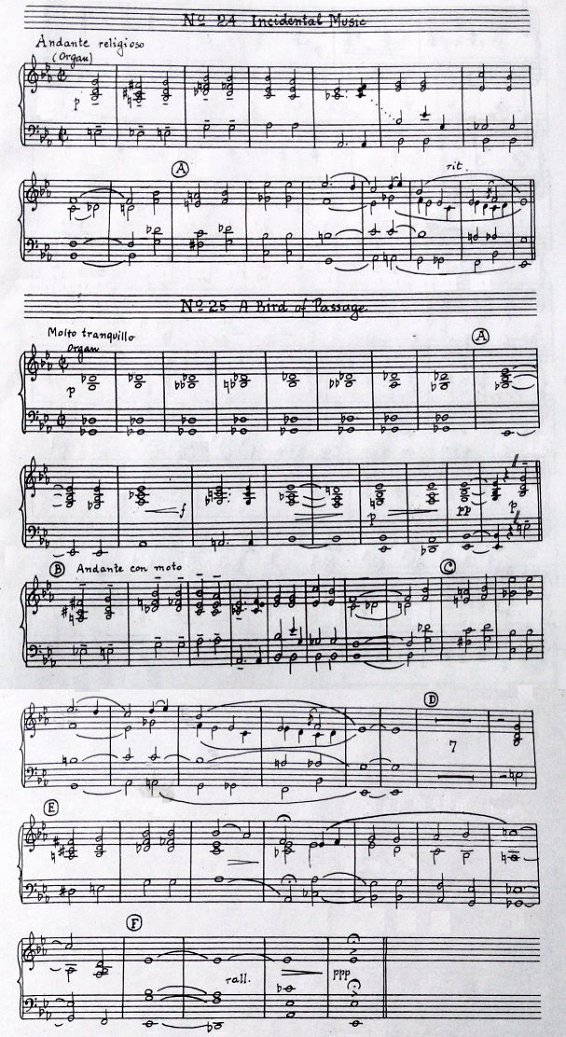

Henry Doktorski also spoke about Kurt Weill's use of the accordion in Lost in the Stars: "Originally the pianist in the orchestra was expected to double on accordion; something which was undoubtedly quite common during the 1930s and 40s. Consequently, there is only one part for piano and accordion, and which instrument is to be played is clearly marked in the part. Composer Kurt Weill uses the accordion (1) sometimes like a reed section as played by jazz accordionists with full right-hand chords, (2) sometimes as a solo instrument (accordion) where it appears as itself, and (3) sometimes to imitate the organ or harmonium. The accordion appears in Lost in the Stars during a dozen different musical numbers, but it is especially prominent in three pieces in particular: "Train to Johannesburg," "Big Mole," and "A Bird of Passage."

During "Train to Johannesburg" Weill uses the accordion like a quartet of saxophones with a much lighter and brighter tone, naturally and sometimes to convey a solo melodic line. In "Big Mole," a humorous song written somewhat in the style of a polka and sung by the lead character's grandson, the accordion is used to double the melody carried by the boy alto, and also provides rhythmic accents. In "A Bird of Passage" the accordion is used to accompany the singing of a hymn (superb four-voice contrapuntal writing, I might add), and is even marked 'organ' in the accordion part, although no organ is specified in the score."

Doktorski continued, "No registrations are marked in the accordion part, but after consulting with maestro Rudel, we decided that the Master stop (one low, two middle, and one high reed) would be appropriate for most of the pieces, except for "Big Mole" where I used the Violin stop (two middle reeds) to make the accordion lighter and less likely to cover the sound of the boy alto, and "A Bird of Passage" where I used the so-called Organ stop (one low and one high reed) to suggest the sound of a harmonium; probably the instrument of choice in African village churches at the time. Maestro many times indicated to me during rehearsals that he wanted MORE SOUND from the accordion. He even asked me to add accordion to the first nine measures of the opening number, because the accordion is an unusual and distinctive instrument in an opera orchestra, and he wanted the audience to be able to hear it clearly."

Train to Johannisburg

Big Mole

Bird of Passage

|