Festival at Prabhupada’s Palace of Gold (c. 1982).

Festival at Prabhupada’s Palace of Gold (c. 1982).

|

Update June 2023: Twelve books of Hare Krishna history by Henry Doktorski are published. This is the complete dodecalogy. Henry says, “It took more than twenty years to finish, but I have completed what I regard as my life’s most important opus. Now I can die in peace, feeling fulfilled! I plan to produce no more books on Hare Krishna history, except perhaps for an index, a seperate volume, so that readers can easily find particular passages in the books. Some have asked me to write a memoir, focusing on my personal life and experiences, but we shall see if that ever manifests.” For more information, see Books by Hare Krishna historian Henry Doktorski.

Update July 2022: Henry Doktorski’s ninth book about ISKCON is available. For more information, see Gold, Guns and God, Vol. 4: “Trials and Tribulations.”

Update June 2022: Henry Doktorski’s eighth book about ISKCON is available. For more information, see Gold, Guns and God, Vol. 6: “The Guru Business.”

Update November 2021: Henry Doktorski’s seventh book about ISKCON is available. For more information, see Gold, Guns and God, Vol. 4: “Deviations in the Dhama.”

Update May 2021: Henry Doktorski’s sixth book about ISKCON is available. For more information, see Gold, Guns and God, Vol. 2: “A Pioneer Community.”

Update March 2021: Henry Doktorski’s book, Killing For Krishna, is available in an Italian edition. For more information, see Uccidere per Krishna

Il Pericolo di una Devozione Squilibrata.

Update November 2020: Henry Doktorski’s fifth book about ISKCON is available. For more information, see Gold, Guns and God, Vol. 1: “A Crazy Man.”

Update November 2020: Henry Doktorski’s fourth book about ISKCON is available. For more information, see Gold, Guns and God, Vol. 5: “The Murder and the Mandir.”

Update October 2020: Henry Doktorski’s third book about ISKCON is available. For more information, see Gold, Guns and God, Vol. 3: “Prabhupada’s Palace of Gold.”

Update January 2020: Henry Doktorski’s second book about ISKCON is available. For more information, see Eleven Naked Emperors: The Crisis of Charismatic Succession in the Hare Krishna Movement.

Update August 2019: Henry Doktorski’s first book, Killing For Krishna, is available in a Spanish edition. For more information, see Sicarios Por Krishna: El Peligro de la Devoción Desquiciada.

Update April 2019: Henry serves as consultant for podcast series: The Hare Krishna Murders.

Update January 2018: Henry Doktorski’s first book about New Vrindaban and ISKCON is available. For more information, see Killing For Krishna: The Danger of Deranged Devotion.

The following pages contain a brief outline of the history (from 1968 to 1996) of the New Vrindaban Hare Krishna Community in Marshall County, West Virginia (established by Kirtanananda Swami and Hayagriva dasa in 1968), compiled by the former New Vrindaban resident, Henry Doktorski, who, during his 15-year tenure at the community (1978-1994), was known to devotees by his Sanskrit initiated name of Hrishikesh dasa.

The idea for the title of this page—“New Vrindaban: The Black Sheep of ISKCON”—was given to me by the General Manager of the community, Kuladri dasa (Arthur Villa), who told me during a 2003 conversation, “New Vrindaban has always been the black sheep of ISKCON.”

In 2002, nearly a decade after leaving the Hare Krishnas and moving to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, he visited the community, met an old friend who used to play in the temple orchestra, and got the idea to write about the history of the music he helped create there between 1986 and 1994—the years of Swami Bhaktipada’s “Great Experiment,” when the Swami instituted a reformation of the temple music, chanting, and garb of the residents which he called “the de-Indianization of Krishna consciousness,” in an attempt to make his brand of religion appear more palatable and less foreign to Westerners. Henry became the community’s first (and only) Minister of Music, and served as: principal organist, choir director, orchestra director, and composer-in-residence.

After a time, Henry decided to expand his article about the music at the community into a book about the history of New Vrindaban, and later decided to make the focus of his book, not on the music reformation or the history of the community, but on Swami Bhaktipada himself: a biography. Although the author has been distracted from the completion of this project, he believes when the time is right, his book will be completed and published.

For more information, please contact the author at

.

.

Part I. The humble origins of ISKCON’s first farm community and its dramatic expansion into the largest ISKCON temple in North America (1968-1985).

2. Gaudiya-Vaishnava Theology

3. Kirtanananda Swami Bhaktipada (b. 1937)

4. “Kirtanananda Is A Crazy Man”

5. New Vrindaban

6. Prabhupada’s Palace of Gold

7. ISKCON’s North American Place of Pilgrimage

|

|

Part II: The Christianization of the style of worship, New Vrindaban as an interfaith “City of God.” (1986-1994)

8. Grand Plans

9. The Krishna Chorale

10. City of God Children’s Choir

11. City of God Accordion Ensemble

12. Music At The Palace

13. The Organs

14. The Temple Orchestra

15. Music Theater

16. The Liturgies

17. Ideational Music

18. Rock and Rap

19. Gospel, Country and New Age Music

20. The Bell Tower

21. Culmination of an Era |

Part III: The fall of the “City of God,” the dissolution of the Christian-style worship, and return to the traditional ISKCON-style worship (ca. 1985-1996)

23. Trials and Tribulations

24. The Exodus

26. Picking Up the Pieces |

I joined ISKCON a scant nine months after Srila Prabhupada’s disappearance. I helped build Prabhupada’s Palace of Gold and accepted first and second initiations from Kirtanananda Swami Bhaktipada. I briefly taught at the gurukula. I served for several months as the president of the Pittsburgh ISKCON temple, and I raised funds for the community on full-time traveling sankirtan as a party leader for nearly six consecutive years. I was instrumental in revolutionizing the “pick” by introducing and developing the “citation line” and became New Vrindaban’s top men’s collector. In 1985 I helped establish the first office for the publication and distribution for Bhaktipada’s books. I traveled to India four times to represent New Vrindaban, including the 1986 Chaitanya Mahaprabhu quincentennial festival in Mayapur.

Later I served as the Minister of Music (principal organist, choirmaster, orchestra director and composer-in-residence) during the “City of God” era from 1986 until September 1993, after which I resigned after concluding that my spiritual master’s authority and character had become seriously deficient. I also participated in the grassroots movement which questioned Bhaktipada’s qualifications for leadership, and eventually recommended returning New Vrindaban to the temple worship style as advocated by the ISKCON founder and acharya, Srila Prabhupada.

I believe the tale of the New Vrindaban Community must be told. Despite New Vrindaban’s return to ISKCON in 2000, some ISKCON devotees, even some in high positions of leadership, may still have mistaken beliefs about Kirtanananda Swami and the community. I hope that this authoritative history can dispel some of the myths which have evolved through the years and shed light on the factual and unembellished story of ISKCON’s first farm community and holy tirtha in the West.

I cannot present a complete and comprehensive history of the New Vrindaban community; such an endeavor could remain incomplete after many dozens of volumes. Yet a journey of a million miles must necessarily begin with a single step, and I consider this treatise to be such a first step: the first history of New Vrindaban. I cordially invite and even challenge other former and current New Vrindaban residents to write about their experiences at the community and share with the world their memories of the fascinating, exciting and sometimes painful story of New Vrindaban. I believe such literature, however imperfectly composed, which describes the glorious successes (and humiliating failures) of the Vaishnava servants of the Lord will benefit devotees throughout the world for many generations to come.

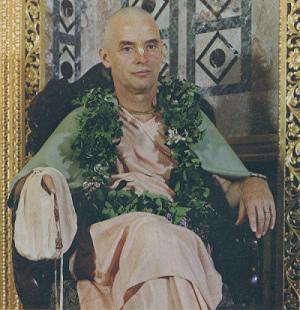

Kirtanananda Swami Bhaktipada at Prabhupada’s Palace (1981)

Kirtanananda Swami Bhaktipada at Prabhupada’s Palace (1981)

|

Precious little can be found in print about Kirtanananda Swami’s life, especially during the early days of ISKCON in the mid- to late-1960s. Satsvarupa dasa Goswami wrote quite a bit about him in his comprehensive six-volume biography of A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, titled Srila Prabhupada-lilamrita, especially in volume 2, “Planting the Seed,” but Satsvarupa conveniently neglected to mention one important period of Kirtanananda Swami’s life: the time he left Prabhupada’s movement for almost a year. This was not an insignificant episode to gloss over, because during this period Kirtanananda Swami first heard about and went to live at to the rundown farm in West Virginia which Prabhupada later dubbed “New Vrindaban.”

Hayagriva dasa also included a great deal about Kirtanananda Swami’s life in his fascinating account of the early days of Prabhupada’s movement, Hare Krishna Explosion: The Birth of Krishna Consciousness in America (1966-1969). Although Hayagriva described in detail the early days of the New Vrindaban community, he also omitted writing about Kirtanananda Swami’s defection from ISKCON in September 1967 and his subsequent joyful and emotional reunion with Prabhupada in July 1968. Neither Satsvarupa, nor Hayagriva, although they were both aware of the 1967-1968 fall down of Kirtanananda Swami, wrote about this embarrassing period of his life, because, I believe, they did not want to tarnish his image as a self-realized soul, transcendental to material nature, befitting his exalted position as an ISKCON guru, a saintly representative of God transmitting purely the teachings of the previous acharyas.

This unknown chapter in Kirtanananda Swami’s life was described in some detail by John Hubner and Lindsey Gruson in Monkey on a Stick: Murder, Madness, and the Hare Krishnas, but their account cannot be trusted one hundred percent as the authors did not present an accurate and scholarly historical document, but a sensationalized and partly-fictionalized version in order to support their hypothesis that Bhaktipada, among all the ISKCON gurus, was “the most ambitious and cruelest of them all,” who “erected America’s Taj Mahal, the lavish Palace of Gold in West Virginia, which became headquarters for a drug ring and ‘enforcers’ who punished and, in some cases, even murdered disloyal devotees.”

About Monkey on a Stick, Professor Larry Shinn wrote, “The book is, at best, a docu-drama which creates dialogue that was never recorded nor ever overheard but, rather, projected back into the mouths of the murder victims by the book’s authors. While it has some factual material at its basis, the book is essentially a sensationalised exaggeration that, if taken seriously, would lead any reader to believe that the Krishnas throughout America condone murder and are violent to their very core.” (Endnote 1)

Unlike the above-mentioned authors, Satsvarupa, Hayagriva, Hubner and Gruson, I have attempted to present a factual historical portrayal of Kirtanananda Swami Bhaktipada, a man whom many devotees, including myself, proclaimed as the “King of New Vrindaban.” Prabhupada affirmed this in a letter to Kirtanananda dated July 27, 1973, “You are Maharaj — Great King. Like Yudhisthir Maharaj and Pariksit Maharaj — Emperor. Actually you are doing something very, very big — so you are Maharaj.” In this book, I have tried to present both the divine and human qualities of a man who was (and still is by many) worshipped as good as God.

Kirtanananda Swami, along with his godbrother, friend and lover, Hayagriva dasa, started the fledgling New Vrindaban Hare Krishna community in 1968 on a ramshackle farm house on 130 acres of hills and valleys in the Northern panhandle of West Virginia. From its beginning the community motto was “Plain Living, High Thinking.” During most of my sixteen years there, Bhaktipada projected the persona of a powerful, charismatic, articulate, wise, magnanimous and renounced leader, who inspired hundreds (if not thousands through the years) of materially frustrated souls (drop outs from mainstream society) to live, work and pray together harmoniously for the express purposes of 1. establishing a self-sufficient Krishna conscious farm community based on agriculture and cow protection, and 2. building New Vrindaban into a holy tirtha: a “transcendental place of pilgrimage where Krishna’s pastimes are displayed in the West.” (Endnote 2)

During its peak in the early-to-mid-1980s, New Vrindaban was undoubtedly the most successful ISKCON community in America. At a time when ISKCON membership recruitment in United States city temples had been declining for years (according to one source, as early as 1975), (Endnote 3) the New Vrindaban community continued to grow in membership and expand to nearly 5000 acres. New Vrindaban publications claimed that 700 full time residents lived at or near the community (this number included children and employees). (Endnote 4)

The mangal-aroti pre-sunrise worship service was normally attended daily by over one hundred devotees, hundreds — and sometimes thousands — of ISKCON devotees regularly visited during major festivals, (Endnote 5) and up to 500,000 tourists visited the Palace annually. (Endnote 6)

|

As I briefly explained above, I lived at the New Vrindaban Hare Krishna community from August 1978 until April 1994. When I joined the community I had just received three months earlier a Bachelor of Arts degree in music. I had studied music for most of my life. In 1963, as a seven-year-old child, I showed some musical talent so my parents enrolled me in the studio of one local New Jersey accordion teacher.

In high school I discovered classical music after joining the school choir. Shortly after, I began serious piano studies and later was awarded a scholarship as a piano major at a small Midwestern liberal arts college. There, along with music, I developed a keen interest in Indian spirituality and the counterculture. I grew my hair long; I heard the former Harvard University Professor-turned-yogi, Baba Ram Dass, lecture at the University of Kansas; I was initiated into Transcendental Meditation for a $35 fee and silently chanted my secret mantra twice a day; I decided to become a vegetarian and even told my piano Professor, much to his chagrin, that after finishing graduate school I would join a spiritual commune somewhere and devote my life to the search for the Absolute Truth. I acquired a packet of LSD from a friend and kept it in the kitchen freezer, intending to expand my consciousness, but never used it because I feared, as a pianist, that it might ruin my music career if I lost my motor control and coordination during a concert performance if I had a “flashback.”

After graduating from college in May 1978, I briefly visited the Maharishi University in Fairfield, Iowa, to check out the scene, but was sorely disappointed; the students there dressed in conservative shirts and ties and wore short hair cuts. I thought they looked a little like fundamentalist Christians. I was looking for something more radical; something less mainstream; something more austere. By chance or by the design of a higher power, on the way home from Kansas City to New Jersey, I visited a former high school buddy who that year happened to have a summer job in Wheeling, West Virginia. While sitting in his barren, hot and stuffy apartment with nothing to do, he suggested, “Why don’t we visit the nearby Hare Krishna community; they’re building a palace for their founder. I’ve been there before; it’s really cool!”

We spent the afternoon touring New Vrindaban and I was impressed. I found a community of spiritual seekers who seemed to practice what they preached: renunciation. They slept for only six hours each night in sleeping bags on the floor of an ashram with twenty or thirty others; they took ice cold baths (there was no hot water) — without even using soap (as far as I could see) — in the communal bath house. The toilets were only holes in the concrete floor (Indian style) without even doors on the front of the stalls! (Endnote 7)

They chanted Sanskrit mantras for two hours daily, usually attended two temple services daily (and sometimes three on Sundays), worked at least eight hours daily for Krishna without remuneration, ate only vegetarian food offered to Krishna, and spoke nothing except topics about Krishna or Krishna’s service.

One of the devotees (Endnote 8) remained perpetually silent except for the words “Hare Krishna” which he would sometimes unexpectedly and loudly shout. Another devotee (Endnote 9) stubbornly refused to wear socks or shoes, even in winter. His feet were heavily calloused and pitted with deep cracks which reminded me of the canals on the surface of Mars. These people obviously were serious about minimizing bodily needs. They were tough; like the Marines. Hare Krishna seemed to me to be the elite “Green Berets” of all the Indian spiritual movements. And the philosophy appeared undefeatable. This is what I wanted: a challenge.

About a month later, I visited the community again during a drive out West and met Kirtanananda Swami for the first time. I was immediately drawn to the warmth and kindness which seemed to radiate from him. He appeared to express genuine concern for me and I listened to him speak as a respectful son listens to a wise and compassionate father. During our first conversation he convinced me (not an easy task) to set aside my music studies and join the commune as a full time devotee to develop my spiritual life. As I had sacrificed a great deal (a potentially promising career in music) to live at New Vrindaban, I decided to give the process a fair chance: I faithfully chanted sixteen rounds daily, strictly followed the four regulative principles, scrupulously attended all the required spiritual programs, resided with similarly-minded godbrothers at the remote Old Vrindaban brahmachari (celibate male student) ashram, and worked to the best of my abilities to help build a ornate memorial shrine for the late founder and acharya of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness: A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (1896-1977) who had passed away only nine months earlier.

My first months at New Vrindaban were incredibly difficult, due in large part to withdrawal from the object of my affections: classical music. During college I had performed with symphony orchestras, sang Handel’s Messiah with a huge 280-voice choir, and even performed a leading role in a concert performance of Puccini’s opera Madame Butterfly. I had composed original music for musical theater productions and directed pit orchestras. But that was all over now. Finis.

From hearing Bhagavad-gita and Srimad-bhagavatam classes I technically understood that most music was simply sense gratification: a highly pleasurable activity which distracted the soul from God and entrapped the living entity in maya’s illusory energy. But God! how difficult it was for me to shed my addiction to classical music! My intellect insisted that I should stay at New Vrindaban, shed my material desires and develop my dormant love for God, but my heart sorely missed the thrill of composing, performing and listening to classical music; the excitement, the glamour, the acclaim, the intellectual satisfaction and the rapturous beauty of the passionate melodies, harmonies and rhythms which had captivated my consciousness for so many years.

I clearly remember working at Prabhupada’s Palace-under-construction, probably in October 1978, doing some solitary gold leafing in the central kirtan hall, crying out in despair from the pain of my mental and emotional anguish and mournfully singing in a loud voice the mahamantra (great chant for deliverance): “Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare; Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare” to the tune of the plaintive Jaya Radha Madhava melody which was sung every morning before the daily Bhagavatam class. I put my entire heart and soul into that chanting; I was suffering so much. I begged Krishna, “Please help me! Please save me! Tear out my material desires from my tortured heart and heal it with unconditional ecstatic love for you!”

Sometime shortly after, apparently by the grace of guru and Krishna, I acquired a taste for devotional service — seemingly overnight — and my mental tempest dissipated like the thick New Vrindaban early-morning fog which is burned off by the rising sun. I requested initiation from Kirtanananda Maharaj: “I would like to become your disciple and spend the rest of my life serving Krishna here at New Vrindaban.” Maharaj beamed joyfully and exclaimed, “Jaya! That’s what I like: someone who comes and does not run away.” (“Jaya” or “Jai” is a Sanskrit exclamation designating approval, often translated as “victory.”) I was initiated on March 13 (Gaura Purnima), 1979, and received the name Hrishikesh dasa (servant of Krishna, who is the master of the senses).

The author working on the Palace dome (summer 1979)

The author working on the Palace dome (summer 1979)

After an intensive six-month construction marathon, the Palace was formally dedicated in September 1979, and soon after I was ordered to go out on the “pick,” (Endnote 10) disguised in a wig and conventional clothes, to solicit funds for the community in parking lots and malls across the country. My temperament was not at all conducive to this life of fraudulent panhandling: passing out a stick of incense, a button, a record, a candle, a flower or a bumper sticker to a passerby, sweet talking him or her into giving a donation (usually under the pretense of a charity for needy kids or Vietnam veterans), sneaking around and running from security guards and police, occasionally spending a few hours (one time three days) in a small-town jail, before being released usually uncharged with any crime but admonished to get out and stay out of town. (Endnote 11)

I suffered so much out on the road. Hardly anybody gave me any money. I was a big failure. The rejection I received from dozens and dozens of potential donors one after another in the parking lots was a greater austerity than taking ice cold showers. (I still had to take a cold shower every morning: after spending the night in a sleeping bag on the floor of a cargo van, I bathed, as did my companions, by stepping outside nearly naked — in summer or winter — and pouring the contents of a one-gallon jug of water over my head.)

One time, after six months of quietly suffering on the “pick,” I returned to New Vrindaban, along with my traveling sankirtan buddies, for one of our monthly three-day visits. We used to hang out at Bhaktipada’s house and sleep at night on the floor in his basement. Once he asked me, “How’s life on the road?” I glumly replied, “Horrible. I can’t make any money. I feel useless. This service is very difficult for me.” He smiled and said, “That’s all right. I never was much good at it either!” I thought this was very funny, as I had read that a pure devotee was expert in everything. Then he quietly suggested, “Perhaps you should return to the farm.”

I remained silent for a moment, turning it over in my mind. His proposal was tempting, but I clearly understood from hearing his classes and darshans (conversations, usually in question and answer format) that he considered traveling sankirtan to be the highest service: “The money is the honey.” I wanted to become a dear confidential disciple. Finally, hoping to please him, I said, “No. I’ll stick it out. Maybe I’ll get the hang of it someday.” Bhaktipada was indeed pleased and affectionately rubbed my shaved head. I was in total bliss.

Somehow, after returning to the “pick,” I acquired rather suddenly the ability to get people to stop and listen to me, reach in their wallet and hand me some money. At the time I attributed this breakthrough to be the mercy of guru and Krishna: a result of my dogged determination to please my spiritual master.

Today however, I wonder if this breakthrough occurred because my natural sense of honesty had finally been sufficiently numbed by untold repetitions of hearing how, if a karmi (fruitive worker, essentially a non-devotee) is tricked into rendering some small service for Krishna, he will make spiritual advancement. We believed we weren’t really lying and stealing from them; we were saving them from hell and blessing them with the priceless treasure of devotional service. We were liberating Laksmi (Lord Vishnu’s consort, the goddess of fortune, a.k.a. money) from people who had stolen her from Krishna. We were taking their money, not to use on our own sense gratification, but to return to Krishna, to glorify God, to help build New Vrindaban. Only when I believed this transcendental trickery from the core of my heart could I look a suspicious potential donor in the eyes and say with complete conviction, “No, I’m NOT with the Hare Krishnas! This money is going to help needy children.” (Endnote 12)

Quickly I learned how to do big on the “pick” and eventually became a maharati, a big gun, a respected party leader for the New Vrindaban men’s traveling sankirtan soldiers. I began collecting $2000 per week, then $3000. Devamrita Swami dubbed me the “Prince of the Pick.” One of my sankirtan buddies (Endnote 13) christened me “The Professor,” perhaps for my skill in training up new pickers.

I was invited to Los Angeles and San Diego expressly for this reason. My visit was a landmark event for New Vrindaban sankirtan; in the past California devotees had slashed our tires when they caught us working their zone. But now things were different; we had something they desperately wanted: a quick and easy way for uneducated and unskilled laborers to make hundreds of thousands of dollars each year.

At the Los Angeles ISKCON temple, Ramesvara Maharaj, the guru for Southern California, even sought me out to converse with me. He was especially enamored of the term I used when referring to the low-class human beings sunk in the modes of passion and ignorance, addicted to sex and intoxication, who frequented heavy metal rock concerts: “the dregs of human society.” He chuckled and repeated that term several times “the dregs of human society,” and even used it once during one of his lectures. (Endnote 14)

After I had learned the tricks of the trade, the necessary detachment from results (it is amazing how much money a person can make if they act as if they can walk away from it all) and oral skills (flattery was a great tool, especially with women), I really started to enjoy life on the road. One year I collected $150,000. I didn’t keep a penny for myself; the money belonged to Krishna.

One pleasant byproduct of my sankirtan success was the attention I received from my spiritual master. Of course, I felt he had always given me whatever attention I needed, but now the relationship became even sweeter. I was the top collector for the New Vrindaban men’s parties during the 1981 Christmas marathon and was honored with the “Golden Van Award.” Consequently I was invited to travel with Bhaktipada in March 1982 to India for the Mayapur festival. I enjoyed serving him, massaging his feet and running menial errands for him. I had developed, by gradual increments, a very deep and sincere love for my spiritual master. I loved him so much that I think I would have done almost anything for him. And Bhaktipada reciprocated by his sweet words and affectionate smiles. He rarely chastised me, but more often he simply encouraged me to do my best, to be all that I could be, to grow and mature in Krishna consciousness.

Bhaktipada and devotees alongside Palace wall, c. 1981. 1st row: unidentified devotee, the author, Dasarath; 2nd row: Krishna Chandra, Jaya Nitai; 3rd row: Jagannath Mishra, Nityodita.

Bhaktipada and devotees alongside Palace wall, c. 1981. 1st row: unidentified devotee, the author, Dasarath; 2nd row: Krishna Chandra, Jaya Nitai; 3rd row: Jagannath Mishra, Nityodita.

One thing I admired about Bhaktipada was his determination to follow Srila Prabhupada’s orders strictly. In 1983 the Bhaktivedanta Book Trust (BBT) published a new revision of Prabhupada’s Bhagavad-gita As It Is, supposedly to correct errors of grammar and style and make the book more acceptable to the academic community. Bhaktipada adamantly opposed changing the books of the previous acharyas without their permission. It might be acceptable if Prabhupada’s original text was included in the new edition as footnotes, perhaps, but this was not done. The words and sometimes meanings of his translations and purports were changed.

Bhaktipada expressed concern that tampering with Prabhupada’s words would set a precedent for changing everything. He believed that, after Prabhupada’s disappearance, no changes at all should ever be made to his books, in order to preserve the purity and potency of his message and to safeguard the permanence of his legacy. Totally reediting the Bhagavad-gita without Prabhupada’s permission was irresponsible and offensive since it violated Srila Prabhupada’s oral instruction to his disciples to follow the age-old tradition of Vaishnava etiquette that prohibits whimsically changing what he had given them. Prabhupada explained the rule of “arsa prayoga,” that whatever the acharya had given should be accepted. The tendency to think oneself sufficiently qualified to correct one’s spiritual authority is not only a breach of Vaishnava etiquette, but is an offense in the service of the spiritual master.

Bhaktipada exclaimed, “In a few years then, they’ll want to change even more, and soon it could become like the Bible — devoid of any clear understanding of the message of God.” (Endnote 15)

Bhaktipada was extremely critical of the BBT decision to allow this sacrilege of changing the acharya’s sacred words. We thought that ISKCON was heading down the road to hell; we felt fortunate to have a spiritual master who held tightly to the previous acharya’s teachings. Once during a darshan I heard Bhaktipada raise his voice and thunder, “I want to become known as the acharya who didn’t change anything!”

I excelled at this service of “picking” for perhaps five years, but, beginning in 1983 or ’84, I began to develop some physical weaknesses which greatly reduced my stamina and collections. I was unable to regularly do big on the “pick” anymore because my body had lost much strength, I believe, partly from the stress of the service itself as well as our customary abuse of and disregard for the body’s needs. We never took a day off and hardly rested. Seven days a week, from 11 a.m. or noon until 9 or 10 p.m. we were out collecting money to help build a new temple for Radha-Vrindaban Chandra (the presiding deities of the New Vrindaban community), which, coincidentally, was never built. On big days when there was a football game or car race we would often start picking at 8 or 9 a.m. and finish late at night, sometimes after midnight. I permanently damaged my voice by working deafening car races which were so loud from the earsplitting roars of the racing engines that I had to shout into a potential donor’s ear before they could hear me. I think my diet was also inadequate; I lost ten or fifteen pounds since moving to New Vrindaban and fell ill more frequently.

Finally in September of 1985 Bhaktipada, perhaps realizing that my days as a big collector were over, asked me to move back to New Vrindaban and help set up an office for the publication and distribution of his books: Bhaktipada Books, later known as Palace Publishing. In late February 1986, I traveled to India for the 500th anniversary of Lord Chaitanya Mahaprabhu’s appearance (March 26) and actually shipped twenty-two cases of books (probably weighing a half-ton) from New York to Calcutta for free on an Air-India jetliner by asking Indian passengers in the ticket line if they would kindly check a case of Hare Krishna books for me on their ticket. (This was 25 years before the security measures were tightened after 9/11.) When the jet arrived in Calcutta I had to rent a pickup truck to get the books to Mayapur, where nearly all of them were sold.

When I returned to New Vrindaban in April, Bhaktipada had a surprise for me: a wife! He didn’t ask me to marry the particular girl he had in mind; he ordered me. (Endnote 16)

When I refused, saying “She’s not my type,” (Endnote 17) he gleefully sent me back on the road on traveling sankirtan. After a month or two, the daily grind of the “pick” got to me again and I begrudgingly surrendered, “Okay, Bhaktipada. I give up. I’ll marry her.” I was actually inspired to do this by my grand-guru Srila Prabhupada, whose father had arranged for him to marry a girl who did not appeal to him. “But father,” Abhay protested, “I am more attracted by the beauty of another girl. Why must I marry this one?” His father philosophically replied, “If you marry a girl who is too beautiful, you will not be able to leave her later in life to take up spiritual practices.” (Endnote 18)

However, after getting married on June 4, 1986, I still had to go back out on the “pick” full time! Bhaktipada got me married and had my sankirtan collections also. Yet by this time there was already a hint of change in the air at New Vrindaban, radical changes which would eventually result in a complete restructuring of the fundamental temple worship services and the predominant dress and appearance of the community. Bhaktipada had begun his most controversial mission: the de-Indianization of Krishna consciousness.

Chant and be happy! New Vrindaban outdoor kirtan, ca. 1989.

Left to right: Truthful, Mahati Mataji, Peaceful Swami (with guitar), Dhananjaya, Vishvamurti, Dhruva (with recorder), Murti Swami, the author (with accordion), Bhaktirasa Swami, Bhakta Steve, Bhaktisiddhanta Swami, Sarvabhauma dasa from Pakistan, Dhirodatta (with guitar), True Peace, Madhava Ghosh

In October of 1986, Bhaktipada once again called me back to the farm; this time to start a choir which would sing great classics by Bach, Handel, Mozart, etc. with Krishna-ized texts: lyrics which had been rewritten to express the philosophy and emotional sentiments of the Vaishnava’s unique perspective on God.

Soon other projects followed and I was asked to lead, at various times, the children’s choir, the accordion ensemble, the gospel choir and band, the temple orchestra, the Music at the Palace recital series, and to compose music for the three daily temple worship services. Music was a very important part of Bhaktipada’s vision for preaching Krishna consciousness and I became an important part of his mission. He even wrote in one of his books, “Krishna clearly says in the Gita that one with a vision for preaching is most dear to Him, and I think that the vision He has given me in regard to preaching with music is best understood by Hrishikesh. So please, just follow his direction and be united in love for one another, because that is what pleases Krishna and Guru.” (Endnote 19)

New Vrindaban “City of God” Temple Orchestra (January 1991).

Accordions: Bhakti-Joy, Dutiful Rama, Chakravarti Swami, Dhruva; Organ: Radha-Vrindaban Chandra Swami; Violins: Yamuna, Good Hope; Double bass: Herapanchami; Harps: Bhavisya, Brihan Naradiya Purana; Trumpets: Vishvatamukha, Sudanu; Percussion: Harikirtan, Wonderful Love.

Bhaktipada and I enjoyed dozens of pleasant and stimulating hours together in his house or on the road in his Cadillac limousine listening to and discussing music, writing and rewriting texts for hymns, and traveling to various cities to listen to pipe organs and purchase instruments for the temple orchestra. However, all things must pass, and so did the glorious era of Western classical music at New Vrindaban. But I am getting ahead of myself.

I never intended to write anything about New Vrindaban until August 2002, when I visited the community and happened to meet an old acquaintance and orchestra member who had served as principle violist in our temple orchestra for several weeks in 1990 and again in 1991: Satyavrata dasa from Toronto. During our brief conversation, he reminisced about many shared old times of creating glorious music for the presiding deities of New Vrindaban, Radha-Vrindaban Chandra, which I had completely forgotten during the passing of the previous twelve years. At that moment, I decided that I must write a short article about music at New Vrindaban, so that the memory of these events would not be lost forever. I did not expect that my article would be published; I began writing simply for my own pleasure.

However, as I pored through my extensive archive of New Vrindaban publications and corresponded with devotees I had not seen for a decade or more, my paper became longer and longer and longer and longer. After a while, I had to divide it into individual chapters, and after three months, I had a 150-page book. After one year it had grown to over 400 pages. After two years I had written over 1000 pages, not simply about the music at the community, but a fairly extensive general history of New Vrindaban which had to be divided into three parts.

What began as a short article had developed a life of its own and had grown into a massive undertaking. Despite the volume of work, I could not give it up; I had already spent so much time on it that I was forced to see it to its ultimate publication. I wanted to provide an accurate historical record and documentation of these glorious and notorious musical activities at a radical Krishna community for posterity, while the memory of those events was still fresh in my mind.

I believe this book is an honest and factual historical account of what happened at the New Vrindaban community. I have taken great pains to insure that the information within this book is accurate. It was not always easy finding reliable sources of information, as the New Vrindaban Temple Library was “purged” soon after Bhaktipada’s rule was terminated. Devotees who wished to “cleanse the temple of heretical writings” and to forget the suffering of the past, emptied the library of “deviant” books and magazines and angrily threw them into the trash dumpster behind the temple, which later ended up being buried at the town dump.

In addition, another extensive collection, the New Vrindaban Archives, consisting of New Vrindaban publications as well as Bhaktipada’s personal correspondence, meticulously organized and maintained by librarian Radha-Vrindaban Chandra Swami and locked and protected by steel bars in the basement of Bhaktipada’s house, was broken into and ransacked by some disgruntled former gurukula students during one reunion at New Vrindaban around 1996 or 1997. Parts of this archive were recovered, but I think some of it was lost.

I also contacted many former New Vrindaban devotees to get their own eyewitness accounts. This was not easy, as some refused to be interviewed, and others, who graciously granted me interviews, didn’t (I suspect) tell me absolutely everything they knew. Some testimonies and sources I did not cite at all in this book, because I believed they exaggerated or distorted the truth. I have attempted to present the opinions of both sides of controversial topics as to present a broader picture. I have tried not to pronounce judgment, but only to tell what happened. If the reader wishes to judge, that is their business.

I believe Srila Prabhupada would agree that truth should be spoken (or written) even when it might be unpalatable to some. One should call a spade a spade. Truthfulness is the last religious quality left in Kali-yuga. If we cannot be truthful, what can we be?

In Bhagavad-gita As It Is (10.4-5, purport), Prabhupada explained, “Satyam, truthfulness, means that facts should be presented as they are for the benefit of others. Facts should not be misrepresented. According to social conventions, it is said that one can speak the truth only when it is palatable to others. But that is not truthfulness. The truth should be spoken in a straight and forward way, so that others will understand actually what the facts are. If a man is a thief and if people are warned that he is a thief, that is truth. Although sometimes the truth is unpalatable, one should not refrain from speaking it. Truthfulness demands that the facts be presented as they are for the benefit of others. That is the definition of truth.”

Hare Krishna!

Henry Doktorski (Hrishikesh dasa)

P.S. Your letters of comment, criticism and correction are welcome and may be sent to

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (February 2003)

The introduction above was written in 2003, when I was still enthusiastic about researching and writing and publishing a history of the New Vrindaban Community. Today I am not so enthusiastic. Certainly I was discouraged during the last few years by my inability to find a publisher for such a specialized book. I have also realized some of my own limitations as an author. However, recently I have become especially discouraged because of all the dirt I have uncovered. Once upon a time I thought that the New Vrindaban Community was basically a good place; a spiritual community where wonderful things were accomplished despite the mistakes of some leaders. The leaders reformed and there would be a happy ending.

However, the more research I undertake, the more horror stories I discover, until now I am not sure whether the New Vrindaban Community was more a spiritual community or more a criminal enterprise operating under the guise of a religious community. Truly I have become disheartened.

And I cannot in most cases ascertain whether my interviewees are (1) speaking honestly, truthfully and factually, or (2) making up sensational horror stories and fabricated fantasies for their own perverted pleasure, or (3) attempting to cover up their own sins and crimes with sanitized versions of actual events. I am not a detective; I really don’t have the time or inclination to spend the rest of my life trying to find out what really happened at New Vrindaban. How many murders were authorized by community leaders and who authorized them (this might come as a surprise to some); how much money to build Prabhupada’s Palace was generated from selling illegal recreational drugs; how much homosexual and pedophilia activity by some of the top men occurred behind the scenes for decades beginning in the late 1960s; including even recreational drug and alchohol use.

I am tired of this never-ending process. Each new lead unearths a plethora of unbelievable atrocities, which in most cases I cannot positively confirm, as when I attempt to interview persons who were implicated in alleged activities they either refuse to speak about it to me, or deny such events ever occurred. And then some others become angry at me for repeating what I have heard which defames the “great souls” who built the community, and then they utter threats to me. Do I really need this?

Perhaps some day this story may be written and published, but I do not see it at this moment. If Krishna sends a qualified and unbiased editor free from attachment to the ISKCON political powers that be, and then provides generous donors to provide funding for continued research and eventual book production, it might be accomplished.

Some devotee friends have recently inquired from me about the progress of my forthcoming book about the history of New Vrindaban. I am pleased to report that, after a period of inactivity and reflection, I have begun working on it again in earnest. For the pleasure of the Vaishnavas, and especially the Brijabasis (former and current), I have uploaded one chapter to the Internet. You can read it here if you like.

The work is still in progress and unfinished, so I welcome your thoughts and impressions about how I can improve it. I apppreciate your input.

Well, once again, I am receiving inquiries about the progress of my book and letters of encouragement from well wishers, including the popular & scholarly Vaishnava author Steven Rosen. I haven’t worked on the book since last September. During the entire summer I worked diligently on the four chapters regarding the murder of devotee Steve Bryant (Sulochan). I was able to fit together many pieces of the puzzle, which has remained hidden for 20 years. However, it was discouraging to me, and even painful, and I lost my momentum. However, now I believe I have recovered from that shock, and have decided to continue researching & writing. I believe it is nearing completion. Thank you for your patience.

I have been working slowly but steadily, more or less, on this monumental work since my last entry five years ago and am encouraged that (1) the manuscript is nearing completion and (2) by the many inquiries I have received from interested persons regarding the status of my work-in-progress. I am nearly finished with the research-gathering stage and am now re-reading my extensive New Vrindaban archives and discovering important bits of information which I omitted when I first read through the archive many years ago.

In the course of the last 30 years I have collected an enormous archive of New Vrindaban-related material: tens-of-thousands of pages, including magazines, newsletters, books, trial transcripts, hundreds of letters from Bhaktipada’s personal correspondence, photographs and sound recordings, and I have interviewed I guess close to 100 people who knew Swami Bhaktipada.

I have two goals in mind: to publish (1) a multi-volume reference work for scholars and students of religion (maybe something like Satsvarupa’s 6-volume Srila Prabhupada-lilamrta, or Hari Sauri’s 5-volume A Transcendental Diary, and (2) a commercial trade non-fiction book for a general reading audience. The former is nearing completion, but the latter is the book that I want to publish first.

Doing so would take condensing all of my research material (currently 1,300 pages and 750,000 words) down to about 300 to 350 pages and 80,000 to 100,000 words. For this project, I might consider collaborating with another writer.

I have not worked on this book for two years. Shortly after writing my previous update of November 2014, I discovered incredibly fascinating information about the early years of the Zonal-Acharya era of ISKCON (1977-1987), which Bhaktipada was, of course, a big part of. I had the good fortune to meet and interview several members of the early Guru-Reform Movement which tried to restrict or overthrow the eleven self-proclaimed “pure devotee” initiating gurus. So much information, as it turned out, that I decided to write a separate book about the Zonal-Acharya era of ISKCON. I felt it was important to document these priceless interviews and get them published before my Bhaktipada biography.

After two years, I completed the Zonal Acharya book in May 2016, and sent out book proposal letters to several dozen publishers. Although most were not interested in my work, one academic publisher showed great interest and sent my manuscript to a “peer reviewer,” a scholar expert in the history of ISKCON. In his review he said that my book was very important and should be published, but that it needed more work to frame it in context with the findings of the works of the great academic authors in this field. So now I have to do more research and writing, but I am nonetheless very encouraged. The last few months, I have spent a lot of time updating my personal website—Henry Doktorski—(updates which were long overdue), and when I am satisfied with my website, I will return to revising my Zonal-Acharya book. When that is finished, I will resume work on my Bhaktipada biography and history of New Vrindaban.

A lot has happened during the last four years since my last upadate. Killing For Krishna was published in January 2018 and Eleven Naked Emperors was published in January 2020. Volume 3 of Gold, Guns and God, is almost ready for publication. It will be followed by Volumes 5, 1, 2 and 4. Everything is happening in its own time. It was 18 years ago when I began my research and writing. Perhaps in a few years all ten volumes of Gold, Guns and God will be published. It has been an enlightening experience.

It's been 22 months since the final volume of Gold, Guns and God was published. I have no more book plans, except perhaps to create an eleventh volume, an index, so readers can easily find particular passages. Once a day, I post excerpts from my books on Facebook. You are invited to the party! Some find my posts valuable, others find my posts offensive. I'll let you decide! See Henry Doktorski III on Facebook.

2. lila ksetram param-dhamam sthapitam yena pascime, from the Bhaktipada pranams. The former goal of creating a self sufficient community based on cow protection and agriculture was supplanted in the mid-1970s by the latter: erecting a transcendental place of pilgrimage where Krishna’s pastimes are displayed in the West. In 1987 the goal was further revised: to create a “City of God” where all God’s devotees, of any faith, could live in harmony.

3. E. Burke Rochford, Jr., claimed in Hare Krishna in America (Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey: 1985), (175-76, 295) that: “Literature distribution doubled each year between 1974 and 1976, then declined modestly until 1979, when it began to fall off significantly. Economically, the growth in book distribution resulted in a financial boom for the movement. . . . As a result of the financial prosperity brought about by this growth in book distribution, ISKCON purchased half a dozen new and larger temples in 1975 and 1976. The decision to acquire larger temples was based on the assumption that the movement’s ranks would continue to grow and that book distribution would continue to expand as it had in these years. By 1975, however, ISKCON’s recruitment numbers had already begun to decline, and in 1977 book distribution began to level off as well. . . . One source suggests that recruitment in America peaked in 1973 and 1974. By 1976, ISKCON’s yearly number of recruits had declined by approximately one-third from its 1973 high. Thereafter, the number of new recruits joining the movement each year leveled off.”

However this decline of enrollment during the mid-1970s is contested by figures published in the Bhakta Program Newsletter which claimed that worldwide recruitment increased until 1979, which was recorded as the highest year (1922 new devotees, and 1335 graduates of the Bhakta Program; an increase of 50% from 1978). Although a large percentage of this recruitment undoubtedly occurred overseases, Danavir Swami nonetheless claimed, “Recruitment, both worldwide and in America, rose steadily from 1970 thorugh

1979.” (e-mail to the author, September 4, 2005)

4. The author examined fifteen census reports in the New Vrindaban archives dating from September 1976 to July 1991 and found that the October 1986 report listed the high point of the community’s population at 377 adults (213 men and 164 women). If we add 136 children and 187 employees to this number we arrive at 700.

5. The October 1982 Brijabasi Spirit proclaimed on its cover, “30,000 Receive the Mercy at Prabhupada’s Festival.” The author believes this was a great exaggeration.

6. “Prabhupada’s Palace of Gold,” Brijabasi Spirit, vol. 10, no. 1 (March 1983), 18. Mahabudhi dasa, the former manager of the Palace, believes that possibly 500,000 visitors came to the Palace in 1985.

7. At the Vrindaban brahmachari farmhouse, like most nineteenth-century farmhouses, there were NO toilets; there was not even an outhouse. We did our morning duties in the rural Indian style by squatting in a field outside. Before passing stool, we stripped to our kaupins (brahmin underwear) in the bathhouse in the basement, donned a special set of rubber boots and coat (designated the “stool coat”), walked outside to a nearby hill sloping down away from the building (and the hand-pumped well), dug a little hole with a shovel, did our duty, rinsed our backside with water from a plastic bottle (designated “the stool jug”), covered the hole with earth, and returned to the bathhouse where we bathed using one of four large plastic 55-gallon drums which were filled with water from the well. We reached into the barrels with an empty plastic milk jug with the top cut off and poured the contents over our heads. In the winter, we did not dig through the snow-covered frozen earth, but just left our “remnants,” which quickly froze solid, on top of the snow. During the spring thaw, we had to be very careful where we stepped, since an entire winter’s worth of stool from 20-30 brahmacharis lay scattered on the muddy ground.

This arrangement was approved by Prabhupada, who wrote, “Concerning the outhouses, if they are not approved, then you can have a septic tank, or pass stool in the open field. I was doing that. I never liked to go to the nonsense toilet so I was going in the field.”

Prabhupada, from a letter to Kirtanananda dated March 23, 1976 from Letters from Srila Prabhupada, vol. 5, (Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, Los Angeles: 1987), 3101.

8. Rantidev dasa. Today I think he probably had serious mental or social problems.

9. Chaidyashatru dasa. Actually, now that I think about it, he did wear rubber boots when he went outside, but no socks. He was once charged—and found guilty—with passing stool in public by the New Vrindaban Judicial Board. See Brijabasi Spirit, vol. 1, no. 17 (August 18, 1974).

10. The “pick:” devotee jargon for going out in conventional clothes to public places like supermarket, shopping mall, concert and sporting event parking lots and “hitting people up” (approaching individuals or groups for a donation). Normally a piece of merchandise like a bumper sticker or baseball cap was offered in exchange.

11. Such deceptive fundraising practices were not limited to the New Vrindaban community but were common throughout ISKCON, in flagrant violation to the Vaishnava principle of satya, truthfulness. Bhakti Ananda Goswami, who became a disciple of Srila Prabhupada at Dallas (1973) and received sannyasa initiation from Radhanath Swami at New Vrindaban (1992), wrote, “These sinful activities rationalized by some ISKCON leaders are not traditionally approved behaviors for Vaishnavas, nor were all ISKCON devotees involved in dishonest or deceptive donation collections. I myself spent many hours on the streets and in mall parking lots distributing Back to Godhead magazines and Srila Prabhupada’s books and never used any deceptions. I also never collected hardly any donations either! When I found out that the brahmacharis [celibate male students] were taking my son out on the “pick” when he was supposed to be in school and were teaching him to lie, I was shocked and removed him from that ‘gurukula.’ I knew many other devotees who did not cheat people. And of course, the deviations of Bhaktipada in these picking schemes were common in ISKCON, but certainly not representative of Vaishnavism, which promotes sattvic behavior, including truthfulness. It is important to make this distinction: the duplicitous, sinful and criminal behaviors sanctioned or indulged in by members of ISKCON and the Hare Krishna movement do not in any way represent the venerable tradition of Vaishnavism.”

Bhakti Ananda Goswami, from an e-mail letter to the author dated February 21, 2003.

12. Bhaktipada disliked the term “deception,” and preferred, like Prabhupada, to compare the rationale of “transcendental trickery” to that of a parent who persuades a child to take a foul-tasting medicine by lacing it with sugar. He said, “Even if it is a little tricky, that isn’t bad.”

Bhaktipada, quoted by Russell Chandler and Evan Maxwell in “Krishna: Earthly Kingdom of Movement Evidences Disarray,” Los Angeles Times (February 15, 1981), 15.

Later Bhaktipada explained, “Even if a devotee, due to over-enthusiasm or lack of discretion, does something that is questionable to get someone to make a donation, that actually is not harmful to the person [giving the donation]; it is to their good that they are engaged in God’s service. In Sanskrit it’s called ajnata sukrti, to unknowingly perform pious activity. This is what’s behind our sankirtan activities: going out and begging from the public to engage them in God’s service, in God’s work. This is actually the highest form of welfare work, because it’s doing what is ultimately good for everyone. If a man gives just a penny, he benefits eternally; his path back to Godhead has begun.”

Bhaktipada, quoted from Gordon Jacob’s video, Holy Cow! Swami (West Virginia Educational Broadcasting Authority: 1996).

13. My dear friend Dasarath dasa and I spent nearly one year together on the road. We were a great team. He was a natural salesman and I was a natural party leader. In the beginning when I was still learning the tricks of the trade, whenever I was having trouble getting donations, I would walk over to Das and listen to what he was telling people. Then I would use his line and people would start giving money. Each town sometimes needed a slightly different mantra. What would work in one town would not necessarily work in another. Even at different times of the day, certain mantras wouldn’t work unless they were subtly changed. Das was a genius at reading the people and finding the exact mantra to use. In fact, Das and I discovered/invented the “citation line,” an innovative fundraising technique which allowed many devotees to triple or even quadruple their collections. Today (February 2003), Das and his good wife (also a former sankirtan maharani) live only a few miles from me. Although he no longer lives at a temple, he still goes out on the “pick” to provide for his wife and family.

14. dregs: 1. the particles of solid matter that settle at the bottom in a liquid, such as beer, 2. the most worthless part.

15. Kirtanananda Swami, cited by Nityodita dasa, “On Tour with Srila Bhaktipada,” Brijabasi Spirit (c. May 1983), 27.

16. Bhaktipada explained how the disciple should obey the spiritual master: “The spiritual master is the representative of Krishna. If the spiritual master tells me to stand on my head, I stand on my head. If he tells me to marry this girl, I marry this girl. If he tells me to do this work, I do this work.”

“Srila Bhaktipada Darshan: Noon, September 26, 1990,” The City of God Examiner, no. 37 (October 3, 1990), 2.

In the early days of his American mission, Prabhupada sometimes also arranged marriages for his disciples. Like Bhaktipada after him, he simply was concerned that his disciples care only to please himself as a representative of Krishna. He said, “And you know our Jagattarini, wife of Bhurijana. She was a theatrical girl and earning millions of dollars. But she has given up everything. She is a nice girl, educated and qualified. But she is satisfied. I asked her to go and marry Bhurijana. She never saw him and did not know what kind of husband she would be accepting. But simply on my word, she came from Los Angeles [to Hong Kong] and got married. The only consideration is how to please Krishna and His representative.”

Prabhupada, cited by Bhurijana dasa, My Glorious Master (Vaishnava Institute for Higher Education, New Delhi: 1996), 89.

17. The spouses of New Vrindaban arranged marriages were often mismatched. Vrajeshvari dasi wrote, “Marriages are arranged by a genius at arranging materially hellish situations (I won’t say who). I mean obviously (it has been said) if it wasn’t for the mahamantra, we wouldn’t, or better couldn’t, be within 50 miles of each other."

Vrajeshvari dasi, “Spiritual Awakening,” Brijabasi Spirit, vol. 3, no. 2 (April 1976), 23.

Mahamaya Devi dasi described her New Vrindaban marriage, “I felt upset when I learned that Kirtanananda Swami wanted me to marry Tribanga dasa, a Spiritual Sky salesman working Indiana, lured to New Vrindaban by promises of a wife, house, maha-prasadam [special foodstuffs offer directly to the deity] and whatever he wanted. . . . Although especially not wanting to marry him, I could see no way out. The next Sunday we were married at a New Vrindaban ‘flower ceremony,’ in which we exchanged flowers on the temple porch at Bahulaban [the devotee farm community on Limestone Road closest to route 250]. Everyone cheered and considered us married. We were given the Deities’ maha-prasadam afterward. The marriage went downhill from that point. . . . It was embarrassing to be married to this man. My unforgiving feelings are most accurately described by a crude expression I learned while growing up: I hated his guts. . . . After eight months of hell, married to Tribanga, I decided to leave him.”

Mahamaya Devi dasi, Srila Prabhupada Is Coming! (Holy Cow Books, Alachua, Florida: 2000), 97, 103.

18. Conversation between Abhay and his father, Gour Mohan De, quoted by Satsvarupa dasa Goswami in The Life Story of His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (Bala Books, Brooklyn: 1983), 4.

19. Kirtanananda Swami Bhaktipada, How to Love God, (Palace Publishing, New Vrindaban WV: 1992), 115.

The following letters and articles by the author, or recommended by the author, have been published online. You may note that about 23 links do not work. They were articles or letters published by Sampradaya Sun. However, the editor/publisher, Rocana dasa, deleted them after we had a philosophical disagreement with the author.

2005/11/15: Vrindaban s Woods and Groves

2006/12/17: A Reply to Umapati Swami, Asked & Answered

2006/12/21: Reply to Bhaktipada or Bhaktifraud?

2007/01/03: Sulocana’s Murder - For the Record, Part 1

2007/01/09: Hrishikesh Replies to Chaitanya Mangala

2007/03/20: Faith Is Blind And Ignorance Is Bliss

2007/03/22: In Memory of Hayagriva

2007/04/01: Prayers For Muktakesh

2007/04/11: The Passing Away Of Muktakesh

2007/04/12: Reply to "Checks and Balances"

2007/04/17: New Vrindaban’s Giant Prabhupada Statue

2008/02/12: Child Abuse in India

2008/03/07: Kirtanananda Swami leaves U.S., Moves to India Permanently

2008/03/29: When Is The Actual Birthday of New Vrindaban?

2008/06/28: A Reply to "New Vrindaban Body Count"

2008/07/24: Confronting the Demons-in-disguise

2008/07/31: Response to "A letter to the Sampradaya Sun"

2008/09/13: http://henrydoktorski.com/nv/Saga_of_Sulochan_1.doc: The Saga of Sulochan, Part 1 (This file has been replaced by Henry’'s book Killing For Krishna)

2008/10/20: http://henrydoktorski.com/nv/Saga_of_Sulochan_2.doc: The Saga of Sulochan, Part 2 (This file has been replaced by Henry’'s book Killing For Krishna)

2009/07/24: Kirtanananda’s Return

2009/09/04: Srila Prabhupada on Eugenics

2009/09/08: Prayers to Lord Damodar

2009/09/12: Noble Qualities

2009/12/16: Krishna Christmas Carols

2009/12/18: We Wish you a Hare Krishna, and a Jai Prabhupada!

2010/01/12: Bhaktipada’s Palace of Love

2010/01/21: A Grand Aparadha?

2010/02/22: Thoughts about Bhaktipada in Karachi and Those who “prop up” Pretenders

2010/08/16: Radhanath Swami’s Alleged Involvement in Sulochan’s Murder

2011/08/10: Saint or Psychopath?

2011/08/22: Interfaith Preaching Is Not Garbage

2011/10/24: Sampradaya Sun Obituary: Kirtanananda Swami Bhaktipada: September 6, 1937 October 24, 2011

2011/10/24: The Wall Street Journal Obituary: Former W.Va. Krishna leader dies in India at 74

2011/10/25: Pittsburgh Post-Gazette Obituary: Swami Bhaktipada / Disgraced leader of Hare Krishnas in W.Va. Died Oct. 24, 2011

2011/10/25: New York Times Obituary: Swami Bhaktipada, Ex-Hare Krishna Leader, Dies at 74 (Part 1)

2011/10/25: New York Times Obituary: Swami Bhaktipada, Ex-Hare Krishna Leader, Dies at 74 (Part 2)

2011/11/14: A History of Neglect: The Cows of New Vrindaban under the Leadership of Kirtanananda Swami

2011/12/02: New Vrindaban Cows Are Doing Fine, Thank You

2011/12/12: A Chronology of Swami Bhaktipada’s Life

2011/12/14: The Jaladhir, Not the Jaladhuta

2011/12/18: Why I Use the Name "Bhaktipada"

2013/01/24: Kirtanananda Swami Biographer requests Devotee Interviews

2013/01/24: Chapter One: This child will become a great preacher

2015/02/08: Salagram-Sila appears at New Vrindaban

2016/10/04: Forever By His Side

2016/11/22: http://henrydoktorski.com/Gold_Guns_God/Murder_of_Sulocana.pdf: Chapter 63: The Murder of Sulocana (This file has been replaced by Henry’'s book Killing For Krishna)