Prelude To Perfection

A frustrated tuxedo-clad long-haired Henry Doktorski is tangled up in material music, while a blissful dhoti-clad shaven-headed Hrishikesh dasa plays the Indian harmonium and sings bhajans in praise of Lord Krishna. Drawing by Carl Carlson (Krishna Katha dasa, ACBSP). This article was first published in Brijabasi Spirit: Plain Living and High Thinking, Vol. II, No. II (February 1982), pp. 24-26.

When I stopped at New Vrindaban [in August 1978], I was merely passing through West Virginia, en route [from my home in New Jersey] to North Texas State Graduate School of Music, where I hoped to earn degrees in opera and piano. Just passing through....Ha! Fortunately I hadn’t reckoned on the power of the pure devotee of God! [1] He alone can rescue the poor fallen soul from Maya’s deadly grip, setting him back on the right path, the road back home, back to Godhead. And I was just passing through! I never did make it to Texas. [2]

In college [Park College, now Park University, in Parkville, Missouri], I discovered [classical] music; the answer to my search for happiness, the ultimate in sense gratification...so I thought. [3] I would practice the piano up to ten hours a day, five days a week, studying Bach, Beethoven and Bartók.

But I was miserable. No matter how long and hard I practiced the piano, I could never perform a piece as well as I wanted to—it would always fall below my standard of perfection. [4]

Eastern mysticism and yoga seemed to be more promising, so I tried many different meditational practices; T. M., hatha-yoga, E. S. T., etc. [5] After a while I concluded that they were all useless. You can only meditate so long and then either you fall asleep, or else you get up and begin performing material activities again. [6]

Time passed by and my melancholy subsided. My philosophical inquiries were pushed into my subconscious mind. At least, that’s what I thought, until I visited New Vrindaban and met Srila Bhaktipada.

My good fortune began one day in [July 1978] [7] when I [on a drive from Kansas City to New Jersey] stopped [in West Virginia] to visit a friend who had a summer job in Wheeling. [8] “Let’s visit the Hare Krishna Temple,” he suggested. “What’s that?” I asked. “It’s an Indian-style palace built on an Appalachian mountain ridge,” he replied. [9]

When we arrived [at New Vrindaban], a devotee showed us around. [10] He explained the sublime philosophy of Krishna consciousness: originally we are all Krishna conscious spirit souls, and the goal of life is to realize that fact by the process of Bhakti Yoga. Upon attaining this platform of self realization, we can go back to Godhead and live eternally in the spiritual world.

I was amazed! Here was a philosophy that satisfied the intellect, and a devotion that satisfied the emotions of the soul. Krishna consciousness was the perfect religion, and it was practical; simply singing, dancing and feasting. [11]

We took a tour of New Vrindaban, stopping at the cow barn, the gardens, the craft shops, the temple, and finally the prasadam room, where I tasted some of the most wonderful food stuffs I have ever had. [12] I was impressed. Here was a community of serious people who practiced what they preached—simple living and high thinking. “Engage in devotional service, go back to Godhead.” They seemed to be successfully renouncing materialistic pampering and self-indulgence in favor of returning to a simpler, more natural lifestyle, in harmony with nature, in harmony with man, in harmony with God. [13]

Before I left New Vrindaban that afternoon, I bought a Bhagavad-gita [14] and thought to myself, “If I ever decide to take up spiritual life, this is where I’ll do it. First I should finish school, get my degree, and set up a nice material situation for myself. I’ll have plenty of time for self realization later.” So, I went back to [my home in] New Jersey, and [after a month or so visiting parents, family and friends, I] began my marathon drive to Texas [in August, to continue my music studies].

By Krishna’s arrangement, it just so happened that I was passing through West Virginia on my way to Texas. [15] Suddenly I saw the Wheeling City exit, which also leads one to New Vrindaban. I hesitated as the ramp appeared alongside me. Then at the last moment I imagined how wonderful it would be to have another plate of halva. [16] Immediately I spun the steering wheel and skidded off the highway. [17]

It was twilight when I reached New Vrindaban. The air was clear and quiet, and the atmosphere seemed to be charged with a spiritual energy of a mystical quality. It felt as if I were leaving the material world behind and entering a new realm of consciousness. [As I knew where the single men’s ashram was located, I quietly climbed the steps to the fourth floor, found a space on the floor, lay down in my sleeping bag, and fell asleep.]

In the morning I awoke when the lights first came on. When I got to the temple room, someone gave me some beads and showed me how to chant.

Suddenly, drums started booming, cymbals and bells began clanging, and everyone hit the floor as if there were an air raid. Not wanting to be the only one standing, I quickly followed suit. When I finally looked up to see what had happened, there was a sharp aroma of incense in the air, the devotees were singing an exotic sounding song [in Sanskrit], and the deities of Radha Vrindaban Chandra were standing before me.

Later on that morning, I met Srila Bhaktipada for the first time. I told him that I was on my way to graduate school where I wanted to study piano and opera. Srila Bhaktipada said he wanted to have operas produced here at New Vrindaban, setting the Vedic epics, like Ramayana and Srimad-bhagavatam to music, and performing them on a grand scale. He told me the story of Lord Ramachandra, and described what a magnificent opera it would be. I could see that he had big ideas, and I envisioned something monumental, a work comparable to Wagner’s Ring Cycle. I picked up on his enthusiasm and exclaimed, “Boy, would I like to have a part in that!” [18] Srila Bhaktipada smiled, and invited me for a ride in his Jeep.

I told him that I was attracted to Krishna consciousness and wanted to give it a try, perhaps even living in the Dallas [ISKCON] Temple and commuting to school every day. Srila Bhaktipada was not so enthusiastic about my ideas. “Spiritual life,” he said, “is right here waiting for you.” [19]

But I was stubborn. “Let me finish school first, then I’ll come back here to help with the opera program.” I could see that New Vrindaban was still a pioneer community, and it would be many years before they got a professional calibre theatre company going, what to speak of an opera troupe.

Srila Bhaktipada continued to stress the importance of becoming serious right now. “Our futures are so uncertain,” he said. “We must be prepared. For one who takes to Krishna consciousness, there is no loss or diminution. When we satisfy Krishna all our material obligations are automatically fulfilled.”

The Jeep rounded the last bend in the rutted road and came in full view of the Palace. The vehicle abruptly came to a halt, there was a moment of silence, and then Srila Bhaktipada spoke. He words penetrated like arrows through my dense cloud of illusion, awakening me from Maya’s dream, opening my eyes to reality! “What use is it to become the greatest pianist in the world if you lose your immortal soul?” [20]

I thought about my parents and college professors, and how disappointed they would be if I didn’t continue my musical studies. “After all,” they would say, “God gave you such a nice talent. Why are you wasting it, instead of using it in His service?” I pondered on that quite a bit and came to this conclusion: There have been thousands of musicians much more expert than myself, who used their talents to glorify God (most notable was Johann Sebastian Bach), but what effect did they have? Were they actually glorifying God or just His creation, His heavens? Did they know God? How many people did they save from the cycle of repeated birth and death? How many people did they convince to give up material life and take up spiritual life? How did they change the consciousness of the world?

All these musicians had great talent and religious fervor, but none of them were pure devotees of the Lord. Therefore, their spiritual potency was nil. Materially they were great, but they had lost their immortal souls. If I wanted to compose, conduct, and perform music which would awaken suffering humanity to the platform of love of God, first I would have to become a pure devotee. Only then would my talent have any value. [21]

Besides, here at New Vrindaban was someone already doing magnificent things to attract millions of people to Krishna. Srila Bhaktipada wanted sincere souls to help him in his monumental mission—to erect for humanity at large a transcendental place of pilgrimage where Krishna’s pastimes are displayed in the West. In fact, who could be a greater composer than he? He’s directing everyone to listen to the sound of Krishna’s words. He’s arranging for the entire world to come and perform their original roles as Krishna’s servant. And when all the lost souls agree to act in such a way, they again become part of the real symphony: the one of transcendental love—the symphony of eternal happiness. [22]

Hrishikesh dasa

New Vrindaban, West Virginia

February 1982

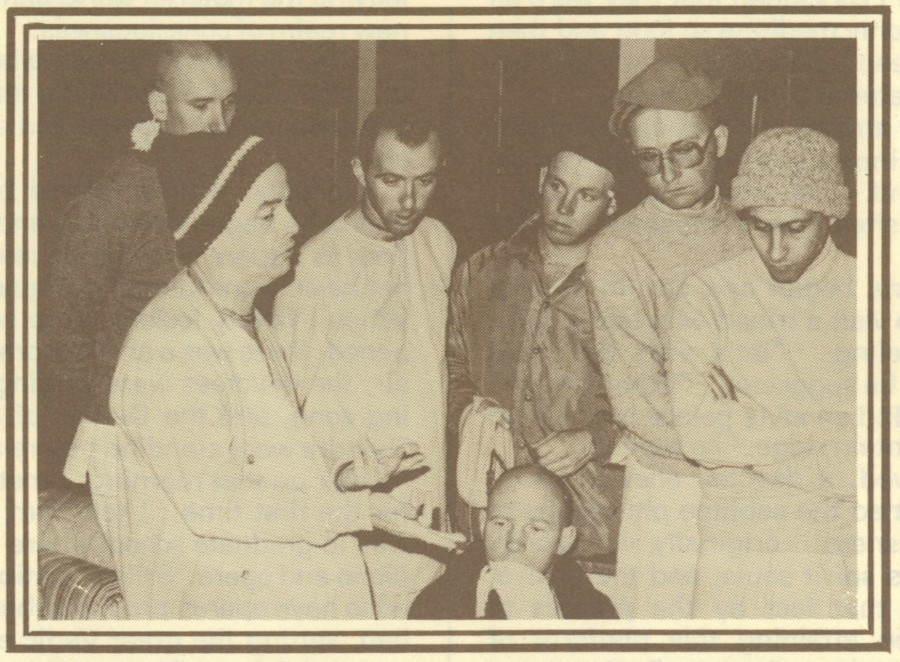

This photo appeared also in my Brijabasi Spirit article. It was taken during a darshan at Bhaktipada's house, right across from Prabhupada’s Palace. We see Bhaktipada, with outstretched hands wearing stocking cap with stripe. Others in the picture are, from left to right: (1) Sudhanu (George Weisner), a New Vrindaban manager, (2) Rishi Kumar (Gary Williams), a construction worker, (3) my godbrother and sankirtan picking partner Dasarath (David Van Pelt), (4) the author, with stocking cap laying on top of my head, and (4) Radhanath dasa Brahmachari. The sankirtan leader, Dharmatma (Dennis Gorrick), humbly sits on the floor at Bhaktipada’s feet.

Endnotes by the Author

1. “I hadn’t reckoned on the power of the pure devotee of God!” Most of us at New Vrindaban at the time, and throughout most of ISKCON, believed that Kirtanananda Swami Bhaktipada was indeed a pure devotee of Krishna: a self-realized bhakti yogi who had transcended the material modes of nature. Even His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, the Founder/Acharya of ISKCON, said so.

2. “I never did make it to Texas.” I never made it to Texas for music studies. I did, however, travel to Texas several times in my sankirtan van while on the pick, collecting money for New Vrindaban. Sixteen years later, in 1994, after I left New Vrindaban, I resumed my graduate studies in music, at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. I received a Master of Music degree, majoring in composition, in 1997.

3. “In college, I discovered [classical] music.” Actually I had discovered classical music in high school.

4. “I was miserable. No matter how long and hard I practiced the piano, I could never perform a piece as well as I wanted to—it would always fall below my standard of perfection.” Although I did not mention this in the article, I had also several failed romances in college, which caused me emotional distress and caused me to doubt myself. This self-doubt contributed to my falling-head-over-heals for a charismatic leader, a father figure, who promised relief from my doubt and suffering. I was going through a very insecure stage in my life at the time, and was ripe for being sucked into a charismatic cult.

5. In 1975, I was initiated into Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s Transcendental Meditation. I paid a fee of $35 and received my mantra, a two syllable word (i-mah), which I assumed was a Sanskrit mantra to help me achieve enlightenment. I liked meditating silently for twenty minutes twice a day. I thought it was a good thing. But when I visited the Maharishi University in Fairfield, Iowa, in July 1978, I was not impressed. I don’t remember studying E. S. T. ever.

6. “After a while I concluded that they were all useless. You can only meditate so long and then either you fall asleep, or else you get up and begin performing material activities again.” This is something I didn’t learn until after moving to New Vrindaban.

7. In the article I incorrectly wrote “August,” but the month was probably late June or early July.

8. My friend was Kenneth Rozyahegyi, one of my chess-playing buddies at Saint Peter’s High School in New Brunswick, New Jersey. He got a summer job teaching art in Wheeling, West Virginia. You can see a photo of us playing chess at my article titled Boys Will Be Boys.

9. Actually, I discovered later that New Vrindaban is nowhere near the Appalachian Mountains. It lies within the Allegheny Plateau, an ancient plateau dissected with deep ravines due to millions of years of stream erosion.

10. This was Jalakolahali dasa (George Meyers). Later I worked under his direction while gold leafing the exterior of Prabhupada’s Palace-under-construction.

11. “simply singing, dancing and feasting.” This is an over-simplification. Propaganda. If you hear this from a devotee, don’t believe it.

12. I didn’t know it, but only the guests got good food. It’s one way they try to hook you. At new Vrindaban, the residents ate simply. Rice and oatwater without ghee, butter or oil for breakfast. I considered it prison rations. Only one day a week, at the Sunday feast, New Vrindaban inmates could get tasty and rich food. Once a week. We lived for Sunday.

13. Yes, I fell for the propaganda. Since then, we have seen that ISKCON itself and the other Hare Krishna splinter sects, are full of conflict and strife.

14. I bought the Gita from Syamakunda dasa (Steven Silberman), who wore very thick eyeglasses. He approached me with a Gita in his hand and asked for a donation. I gave him a ten dollar bill. He was shocked. He later told me he expected me to give him two dollars. I took the book to New Jersey, and read a little bit. I found the translations interesting, especially in the second chapter, but I thought the purports were rather disjointed; jumping from topic to topic. But I did chant Hare Krishna while back in New Jersey, and I thought it was a good thing.

15. Actually Krishna didn’t arrange; I arranged to stop at New Vrindaban and stay for two or three days to more thoroughly check out the scene. I planned on staying for a while. However, as noted in the article, my short stay turned into a long 15-16 years.

16. Halva is a dessert common in Northern India and Pakistan, a delicacy made by combining wheat farina with milk, sugar, clarified butter, cardamom, saffron, and nuts such as almonds and pistachios. Often raisins or dates are added.

17. There is more to this story than I revealed in the Brijabasi Spirit article. As mentioned earlier, I planned to spend the night at New Vrindaban and stay a few days. However, while driving west on Interstate 70 in Wheeling, as the exit approached, I heard a voice in my head warn me, “If you turn off the freeway here, you will never get back on again.”

Whoa! Actually, I didn’t hear a voice in my head; but a thought entered in my mind, like an omen. I wondered, “Maybe I should just keep going on the freeway into Ohio and find another place to spend the night.” As the exit came closer and closer, I was unsure what to do. Finally, at the last second, I remembered how hungry I was and how delicious was the New Vrindaban prasadam, so I hit the brakes and spun my steering wheel to turn off onto the Wheeling exit. The prophecy which appeared in my mind, in retrospect, was quite accurate.

18. Twelve years later, my musical titled Journey To The City of God for singers, actors, dancers and chamber music ensemble was performed in the New Vrindaban temple during an interfaith conference. Curiously, my first musical was not based on the Ramayana nor Srimad-bhagavatam, but on Bhaktipada’s recently-published book, Devotee’s Journey to the City of God, which was based not on Vedic literature, but on Christian literature: John Bunyan’s 1678 classic allegory Pilgrim’s Progress.

To learn more about Journey To The City of God, and to listen to three different recordings of the musical, go to Journey To The City of God.

19. Today I know that Bhaktipada and the zonal acharya for Texas, Tamal Krishna Goswami, were in competition with each other. Bhaktipada would not be happy if I joined ISKCON in Tamal Krishna’s zone and took initiation from him.

20. Here, Bhaktipada paraphrased the words of Jesus Christ as quoted by the Evangelist Mark: “For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?” (Mark 8:36)

The article gives the impression that Kirtanananda Maharaja convinced me to move to New Vrindaban immediately, but that is incorrect. After he paraphrased Jesus, I felt that he had defeated me. At that time, I decided that I would simply delay my graduate school studies for a semester. I would stay at New Vrindaban for about four or five months to study Bhakti Yoga. If, by January 1979, I was not totally enamored with life at New Vrindaban, I would exit and resume my studies. As it turned out, around October or November, I had a conversion experience, and decided to stay at New Vrindaban indefinitely.

21. Today I do not agree with these arguments.

22. Please do not think I am inimical to Bhakti Yoga. I think Bhakti Yoga is a great discipline. I still follow many of its precepts, and I still chant Hare Krishna. I just don’t like the exaggerated hype I got at New Vrindaban and in ISKCON, not to mention abuses and cheating by the leaders.

Henry Doktorski

March 28, 2025

| Back to: Gold, Guns and God |