Ideational Music: Gaur Aroti and Prayers to Lord Nrsimhadeva

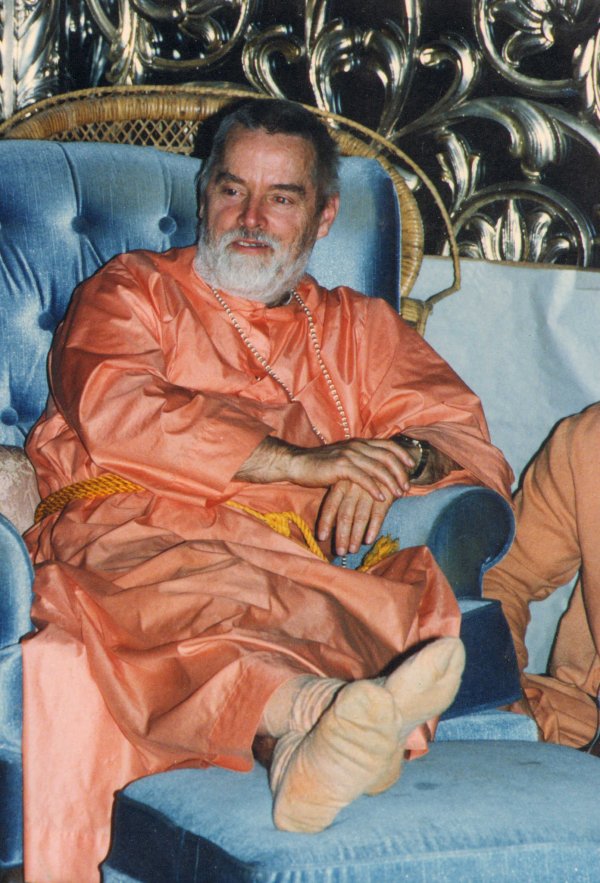

Bhaktipada relaxes and gives darshan to his disciples and followers in the temple room at his house following the evening service.

Ideational Music: from Gold, Guns and God, Vol. 8:

IN 1991, BHAKTIPADA HAD A NEW VISION for the music at New Vrindaban; a type of music he called “Ideational.” His inspiration for the New Vrindaban City of God was that everything should remind one of Krishna, or God. The architecture should be in the mode of goodness and should have a simple but beautiful classical style. The robes of the residents should also be in goodness and reflect simplicity and austerity of dress. The food, of course, should also be in goodness: pure vegetarian Krishna prasadam, and the music should be ideational: completely free from the degrading modes of passion and ignorance.

Three cyclical ages of humankind

During the autumn of 1991, Bhaktipada read a book by the Russian sociologist Pitirim A. Sorokin (1889-1968), The Crisis of Our Age, which postulated that human history was caught in a titanic cycle of alternating materialistic and spiritual cultures, each collapsing and being replaced by the other over the span of many centuries. Sorokin defined three cyclical ages of mankind: (1) Ideational, (2) Idealistic and (3) Sensate.

According to Sorokin, the Ideational Age last appeared during the Middle Ages and was exemplified by Western medieval culture, as its major principle or value was God. Its architecture and sculpture were the “Bible in stone.” Its literature, again, was religious. Its painting articulated the same Bible in line and color. Its philosophy, almost identical with religion and theology, was centered around God. Its ethics and law were but an elaboration of the absolute commandments of Christian ethics. Its political organization was predominantly theocratic and based upon God and religion. Its family, as a sacred religious union, was indissoluble and articulated the same fundamental value. Even its economic organization was controlled by a religion prohibiting many forms of economic relationships. And its music was almost exclusively religious: Gregorian chants such as Alleluia, Gloria, Kyrie Eleison, Credo, Agnus Dei, Mass, Requiem, etc.

Sorokin claimed that at the end of the twelfth century, there emerged the germ of a new—and profoundly different—major principle: that the true reality and value is sensory. Only what we see, hear, smell, touch and otherwise perceive through our sense organs is real and has value. Beyond such a sensory reality, either there is nothing, or, if there is something, we cannot sense it; therefore it is equivalent to the non-real and the non-existent and as such, may be neglected. Sorokin called this the Sensate Age, which eventually, by the end of the twentieth century, effectively and efficiently supplanted and destroyed the former Ideational Age, relegating it to a mere vestige of its former power and influence.

During the Sensate Age, architecture and sculpture is predominantly secular. Its literature, again, is secular. Its painting, philosophy and theology is centered around man, not God. Its ethics and law are separated from God and religion. Family relationships are considered temporary and divorce is common. And its music extols the pleasures of the senses. From the hit songs of the late-nineteenth century such as My Wild Irish Rose and When You Were Sweet Sixteen, to the hit songs a hundred years later such as Erotica by Madonna and Bitch by Eminem, mention of God (or virtuous qualities like renunciation or self-control) became conspicuously absent.

Sorokin described the Idealistic Age as the time between the Ideational and Sensate ages, which lasted approximately eight centuries, from the twelfth to the twentieth centuries. Its major premise is that the true reality is partly supersensory and partly sensory; it embraces the supersensory aspect, plus the rational and the sensory aspects of human understanding.

Sorokin described an Ideational Age which, in some ways, seemed to correspond to the mode of goodness. The Idealistic and Sensate Ages seemed to correspond to the modes of passion and ignorance. Bhaktipada said he wanted to root out all sources of passion and ignorance in New Vrindaban and replace them with goodness. In 1987, television and radio—due to materialistic programming—had already been officially banned by Bhaktipada’s proclamation. (Actually television and radio had never been permitted in the community, but it had to be officially banned, as some householders began to acquire television sets during the mid-1980s.)

Bhaktipada had asked devotees to give up driving their cars in the community and ride bicycles or horses instead. He purchased a horse-drawn buggy in which he rode around the community. He also recommended that his disciples eat a salt-free diet based on pureed raw vegetables. Bhaktipada claimed, “Your diet should consist of at least one half raw foods, because cooking kills the food. No hot, spicy foods—they agitate. A little salt, but not too much.”

And Bhaktipada wanted the New Vrindaban residents to listen to sattvic music which would not agitate the senses; music which would calm the mind and passions; ideational music like Gregorian chant.

Bhaktipada speaks to disciples, followers and guests in the temple room at his house following the evening service.

Ideational music choir commissioned

Hrishikesh dasa explained:

On Bhaktipada’s order, I organized a choir to sing ideational music, numbering about 20 voices, which included interfaith members like Ariel. I then set the Gaura Aroti Prayers to a chant of my own composition and began training the choir to sing it for the evening services at the temple. The chant was not meter-less, as in Gregorian chant, but the tempo was extremely slow and in a minor key. When the prayers were finished, the devotees chanted Hare Krishna to the melody: a plaintive call to the Supreme, a lament of the soul crying out to Krishna for shelter. It was a very sad tune, but I am well acquainted with sad tunes.

For example, fourteen years earlier, in September/October 1978, I served at Prabhupada’s Palace-under-construction by gold-leafing the capitals on the square marble-covered columns in the kirtan hall. Most of the time I had a partner, such as Jalakolahali or Jagat Pate, but sometimes I worked alone for hours a day. At the time, I suffered greatly, as I sorely missed my old life of music studies, my family and friends, and going out with attractive young women. I often wondered why I chose to stay at New Vrindaban instead of continuing my graduate music studies at North Texas State University. Deep down, I understood there was value in studying bhakti yoga under the tutelage of Kirtanananda Maharaja, but the emotional pain of withdrawal from the objects of my affection was at times unbearable.

I remember one particularly miserable day when my depression was unusually unendurable. While standing on a ladder and applying gold leaf to the capitals, my emotional angst became so intense that my heart felt vacant of meaning and full of sadness. In this profound depressed state of consciousness, I sought solace by chanting the Hare Krishna maha-mantra with all my heart and soul in a loud voice to the tune of Jaya Radha Madhava, which is the song which is sung each morning prior to Srimad-bhagavatam class. It’s a plaintive, mournful tune, full of deep emotion and longing. When I worked alone that day in the kirtan hall and sang that tune with all my heart, tears came to my eyes, so empty was my heart, so wretched was my anguish.

In 1992, I felt my new ideational tune for the evening aroti was in a similar spirit as the Jaya Radha Madhava tune: in the mood of a suffering soul crying out to Krishna for help. Some Brijabasis said my tune sounded like a dirge. It made them depressed. But that was the point of my tune. It was meant to evoke that feeling of sadness in the listener.

My tune was meant to mirror Lord Chaitanya’s own heartache and grief, “O Govinda! In separation from you, a moment feels like twelve years or more. Tears flow from my eyes like torrents of rain, and my heart is vacant due to your absence. O my Lord, out of kindness you enable me to easily approach you by your holy names, but I am so unfortunate that I have no attraction for them.” Great music, poetry and art doesn’t always have to express a joyful and happy mood. Like Lord Chaitanya’s Siksastaka Prayers, great music, poetry and art can also express intense pain.

Our New Vrindaban choir premiered my ideational chant at the February 16, 1992 Interfaith Conference and also performed it during evening arotis at Bhaktipada’s house and at the temple. The Covenant Church gospel choir from Pittsburgh also performed at that conference, with much swaying to and fro, hand clapping and foot stomping. Not surprisingly, they were the big hit of the festival. One New Vrindaban resident said, “When the Covenant gospel choir performed I remembered how we used to dance and clap when we sang the traditional kirtan in Bengali and Sanskrit. It made me miss the old-time kirtans.” (Gopalasyapriya devi dasi)

For the record: these two photos taken at Bhaktipada’s house are from 1991, before he was convicted in the March 1991 racketeering trial. This recording was made at Bhaktipada’s house in 1992, when he was under house arrest in Warwood, a neighborhood of Wheeling, West Virginia. Even in Bhaktipada’s absence, we still used to celebrate the evening aroti at his house.

Two Recordings of Ideational Music at New Vrindaban

(1) To listen to the first performance of the Ideational Choir at the February 1992 Interfaith Festival at New Vrindaban (February 16, 1992), followed by the performance of the Covenant Church of Pittsburgh Gospel Choir, go to YouTube.

(2) To listen to an evening aroti at Bhaktipada’s house (Spring or Summer 1992) featuring the Ideational Gaur Aroti and Prayers to Lord Nrisimhadeva, go to YouTube.

Musicians and singers on the recording at Bhaktipada’s house:

Accordion: Hrishikesh

Bass Accordion: Dutiful Rama

Cantor: Brihan Naradiya Purana devi dasi

Invocations: English lyrics by Umapati Swami, music by Hrishikesh dasa

All glories to you, Bhaktipada

Lord Krishna's servant dear.

You worship at his feet and spread

His message far and near.

O servitor of Prabhupada,

You've founded in the West

A city where Lord Krishna's love

And pastimes manifest.

All glories to you, Prabhupada,

Lord Krishna's servant dear.

You worship at his feet and spread

His message far and near.

O Saraswati Deva,

You've spread the Holy Name

And saved the Western countries from

Impersonalist shame.

The Aroti of Sri Gaur Hari: English lyrics by Umapati Swami, music by Hrishikesh dasa

(1) All joys, all glories ever more!

How beautiful the holy sight—

The aroti of Sri Gaur Hari,

In New Vrindaban’s hills tonight.

(2) Above Gauranga’s lotus head,

Srivasa holds an umbrella high.

Gadadhar’s on the Lord’s left side,

While Sri Advaita stands nearby.

(3) The Lord sits on a jeweled throne

With Nityananda on his right.

The demigods with Lord Brahma

Perform the aroti through the night.

(4) They cool the Lord with cham’ra fans—

Sri Narahari and his friends,

Sanjay, Mukunda, Vasu Ghosh

Lead songs of joy that never ends.

(5) Guitar and organ, bells and drums

Create a sweet melodious sound,

Enchanting all the universe,

Attracting minds for worlds around.

(6) And Lord Chaitanya’s shining face

Defeats the moon a million fold.

The forest garlands round his neck

Reflects the hue of molten gold.

(7) Narada, Suka, Siva too

Have lost their speech in ecstasy.

And Srila Bhaktipada is here

For aroti to Sri Gaur Hari.

Prayers to Lord Nrsimhadeva: English translation by Umapati Swami, music by Hrishikesh dasa.

All glories to Nrsimhadeva,

Prahlad finds joy in you alone.

You killed Hiranyakasipu,

Your nails, like chisels, cutting stone.

(1) Nrsimhadeva is everywhere,

Within the heart and outside too.

O source of all, O great refuge,

Let me surrender unto you.

(2) The beauty of your lotus hands,

Each wondrous nail sharp as a sword.

The wasp Hiranyakasipu

Was ripped apart by these, my Lord.

(3) O Keshava, O Lord Hari,

All glories to this form sublime.

Half man, half lion, God of all,

You rule the worlds through endless time.

| Back to: Gold, Guns and God, Vol. 8 |