The Accordion in Frida the Opera

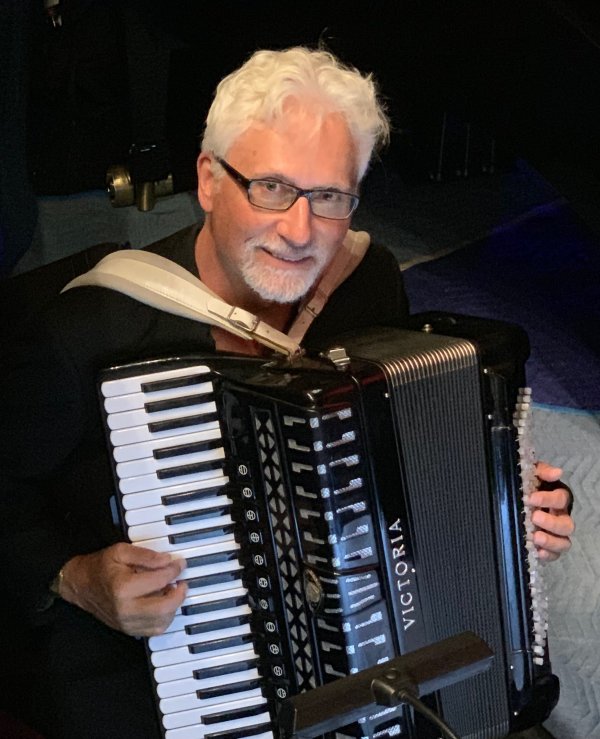

Henry in the pit for Frida the opera. Photo by Suzana Beites.

October 5, 9, 11 and 13, 2019: Henry performed on accordion for four performances of Frida by Robert Xavier Rodríguez with the Atlanta Opera. Music rehearsals with the Atlanta Opera Orchestra, under the directon of Maestro Jorge Parodi, began on September 24th. USA Today noted, “[Frida is] an exciting, long overdue musical biography. Raw, wonderfully dangerous theater.”

The Atlanta Opera’s website explained, “[Frida is] a fantastical theater piece combining pantomime, puppetry, movement, and vocal performers, Frida enlists mariachi instruments to heat up this blend of tango, zarzuela, ragtime, 1930s jazz, and vaudeville. The story conjures a vivid portrait of the courageous revolutionary and magical realist Frida Kahlo as she struggles with her torrid marriage to Mexican muralist Diego Rivera.”

Henry spoke about the accordion in Frida:

“When I received the August 15th email message from the Associate Conductor and Chorus Master of the Atlanta Opera (Rolando Salazar) asking if I’d be interested and available to play the accordion part in Robert Xavier Rodríguez’s opera Frida, I was, naturally, interested, but was I available? ‘Perhaps,’ I replied. I thought I might be able to get permission from House of Prayer Lutheran Church to take off three consecutive weeks as organist. But finding a substitute organist to take over for me for six Sunday services and three Wednesday choir rehearsals? That would not be easy. In addition, I’d have to find a substitute chess teacher to take over seven Chess4Kidz classes at HomeSchool Murrieta. But fate was with me, and I got the permission, the substitute organist and the chess teacher. Now I could play with the Atlanta Opera Orchestra in their run of Frida!

“However, that was only the beginning of the story. Soon after arriving in Atlanta, I discovered that the accordion part was not easy to learn. For starters: it was 169 pages of music, and the accordion hardly shut up during the entire full-length two-act opera. Later, Maestro Jorge Parodi told me, ‘Frida is [practically] an accordion concerto. The accordion is THAT IMPORTANT in the orchestration.’ While most of the part was not technically difficult, there were many, many sections which demanded the most-efficient fingering and a good deal of practice.

“After a few rehearsals I discovered that my challenges had just begun. The most difficult aspect of the accordion part was the hundreds of fermatas and tempo changes. The accordion part was so prominent that I had to understand and know the entire score. Many hours were spent in rehearsal with the orchestra, in private practice myself, and about eight hours in four extra sessions with only Maestro Jorge Parodi and myself, in which he would play piano with his left hand, conduct with his right, and I would play the accordion part. These sessions were very important for me to perfect my part, and for this especially, I am extremely grateful to Maestro Parodi.

“This was the most difficult piece I had ever played. In an August 3rd Facebook post, I explained: I thought learning 169 pages of Robert Xavier Rodríguez’s music from his opera Frida would get easier the more I practiced, or rehearsed with the orchestra, or met privately with the maestro (we met together thrice already, and I have a fourth appointment for tomorrow). Today was our dress rehearsal and I AM EXHAUSTED!

“I’ve never pumped those bellows as much as I have during these last ten days in Atlanta. The left side of my body is aching. And today the maestro told me, ‘The accordion needs to be louder!’ That means I’ve got to pump harder than ever.* I’ve played dozens of concerts with symphony orchestras during the last 25 years, and this is the most challenging gig of all. Even more exhausting than David Del Tredici’s Final Alice—(he wrote a MONSTER accordion part), which I played with the Pittsburgh, Cleveland and Detroit Symphony Orchestras. Or Astor Piazzolla’s Concerto por Bandoneon, or Tres Tangos, or Adios Nonino, which I played with orchestras in Virginia, Pennsylvania, Iowa, Illinois and Indiana, and Fairbanks, Alaska, to name a few.

“Part of the challenge is that there are hundreds of fermatas and almost as many tempo changes, accelerandos, etc. so I have to watch the conductor constantly, and that means a considerable portion of this music MUST be memorized. What was I thinking when I accepted the Atlanta Opera’s offer to play accordion for Frida? No rest for the wicked, I guess. Oh, I’m not complaining. Actually, I ENJOY the challenge. This gig is making me stretch my borders, and it challenges my musical skills (and my physical and mental endurance). And it’s SO WONDERFUL to play with such fine symphony musicians, and great opera singers, and work under the direction of such a great conductor as Jorge Parodi. I’m sure everything will be fantastic on opening night. I can hardly wait!’”

Henry later explained, “Suddenly, it seemed, during the afternoon preceding opening night, everything fell into place. My dogged determination to master the accordion part and understand the intricacies and complexities of the opera had succeeded. It was like a revelation to me. Of course, from the beginning I understood this would happen; I just didn’t think it would take so much time and practice and entail so much hard work. On opening night, I was extremely happy with the Frida performances. Everything worked out well, and the composer, Robert Xavier Rodríguez, who attended the opening, told Maestro Parodi that he really enjoyed hearing his opera performed by the Atlanta Opera. The result was certainly worth the great effort.”

In addition, Suzana Beites, a fellow accordionist and educator who performs regularly with two ensembles—the Accordion Pops Orchestra based in New Jersey (billed as “the largest professional accordion orchestra of its kind on the East Coast”), and the Hudson Valley Accordion Ensemble based in Upstate New York—flew from New Jersey to Atlanta to attend the opening night performance and noted, “Henry is diligent and professional. He was spot on!”

* I discovered a solution to our accordion volume problem. When the pit was assembled, the powers-that-be decided that the piano was too loud, and so they had stage hands install thick cloth mats under the piano and alongside the pit wall to soak up the sound. Unfortunately, the accordion was sitting right on that mat and the mat stretched along the pit wall on the accordion’s right side. In essence, the sound of the accordion was getting sucked up by the thick cloth mats! I spoke to Maestro Parodi about this. He agreed with my assessment, and he ordered that the mats under and alongside the accordion be removed. The next time we performed (opening night), the accordion was noticeably louder and more clear.

Reviews of Frida were written by Stephanie Adrian of ARTS ATL, and Mark Gresham of EarRelevant. In addition, OPERAWIRE featured Frida as one of the top five operas in North America to see this weekend. Daniel Weisman in SCHOMOPERA, praised the conductor and orchestra by noting, “The sensistive undertones of conductor Jorge Parodi’s chamber orchestra.”

The Plot

ACT I

Scene 1—The Street outside the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria, Mexico City, 1923. Three Calaveras, death figures from Mexican folklore, introduce the scene. Schoolgirls enter. They are accosted by the unruly male gang of Cachuchas, led by the young Frida Kahlo and her boyfriend, Alejandro. Frida’s sister, Cristina, upbraids Frida for her boyish behavior. The Cachuchas chase off the schoolgirls, and Frida watches as a Mother whose child has died begs a Petate (straw mat) Vendor for a mat to bury her son. Frida is moved by the poverty she sees. She then witnesses a celebration of the Zapatista movement and takes heart in the promise of the revolution.

Scene 2—Frida’s Room, Coyoacan. Frida tells Cristina of her expectations of life upon coming of age.

Scene 3—The Bus Crash, Mexico City. Frida and Alejandro kiss and board a bus. The bus crashes, and the scene is enacted by the Calaveras to the tune of a corrida. Frida is severely injured, but she resolves to live and to begin her life as a painter.

Scene 4—Diego’s Mural at the Preparatoria/Wedding. As Diego Rivera paints, his wife, Lupe Marin, poses. Frida and Cristina enter, and Frida presents her portfolio to introduce herself to Diego. Diego is fascinated by Frida. He leaves Lupe to ask Frida’s father, Guillermo, for Frida’s hand in marriage. At the wedding ceremony, Lupe dramatically appears and makes a futile attempt to win Diego back.

Scene 5—Diego’s Studio. Frida critiques Diego’s work as he paints a portrait of Emiliano Zapata. They are interrupted by revolutionaries, communists, businessmen and government bureaucrats. All denounce Diego and tell him his career as an artist is finished in Mexico. He fires his pistol at them, and the Riveras resolve to try their luck in the USA.

Scene 6—New York City. Frida and Diego attend a dinner party hosted by the Fords and the Rockefellers. Diego enjoys the adulation, and Rockefeller commissions a mural. Frida ridicules the rich in “Gringolandia” and gives a spirited interview to a group of reporters.

Scene 7—The RCA Building, Rockefeller Center, New York. In a split scene, Diego works on his commission, Man at the Crossroads, while Frida paints. She is in despair at being unable to bear a child. Rockefeller berates Diego for displaying his communist sympathies by including Vladimir Lenin in the painting. The mural is destroyed, and Frida miscarries. She persuades Diego to return to Mexico.

ACT II

Scene 1—San Angel, Mexico. At home in adjacent blue and pink houses, Frida expresses her joy at being home in Mexico. Diego is miserable. Frida chooses to ignore the parade of women through Diego’s house, but she is horrified to discover her sister, Cristina, among them.

Scene 2—San Angel, Mexico. The communist Leon Trotsky and his wife, Natalia, join the Riveras in Mexico. Diego and Natalia confront Frida and Trotsky over their mutual affection. Cristina expresses her guilt for betraying Frida. Frida and Diego come to the realization that their differences cannot be reconciled.

Scene 3—Frida’s Bath. Frida retreats to the seclusion of her bath and the comfort of a female lover.

Scene 4—An Art Gallery/New York Apartment of Nicholas Murray, Photographer/Back in Mexico. Diego meets with the American actor Edward G. Robinson and sells him some of Frida’s work. Diego then urges Frida to pursue her own career, without him. Frida models for her lover, and talk to him as he photographs her. Frida and Diego decide to divorce.

Scene 5—Frida Imagination. Haunted by her physical and emotional pain, Frida joins the Calaveras in depicting imagery from her paintings The Broken Column, The Little Deer and Self Portrait With Monkeys.

Scene 6—Finale—Frida’s Hospital Bed. In a delirium, Frida relives episodes of her life, including the assassination of Trotsky, of which she and Diego were accused. Diego returns and sings to entertain her, finishing with a proposal to marry her again. She agrees, saying he must realize that she is now her own creation, independent of him. The Calaveras and the entire cast join her, singing and dancing in a joyful celebration, and she departs with a cry of “Viva, la vida, alegría, and Diego.”

Notes by the Composer

As noted at the website of Robert Xavier Rodríguez:

Rodríguez describes Frida as being “in the Gershwin, Sondheim, Kurt Weill tradition of dissolving the barriers and extending the common ground between opera and musical theater.” In keeping with the Mexican setting of Frida, he has created a unique musical idiom. The score calls for mariachi-style orchestration (with prominent parts for accordion, guitar, violin and trumpet), in which authentic Mexican folk songs and dances are interwoven with the composer’s own “imaginary folk music,” tangos and colorations of zarzuela, ragtime, vaudeville and 1930’s jazz—all fused with Rodríguez’ characteristic “richly lyrical atonality” (Musical America) in a style “Romantically dramatic” (The Washington Post) and full of “the composer’s all-encompassing sense of humor” (The Los Angeles Times).

Among the “stolen” musical fragments developed in Frida (like Stravinsky, Rodríguez says “I never borrow; I steal.”) are such strange musical bedfellows as two traditional Mexican piíata songs (“Horo y fuego” and “Al quebrar la piíata”), two narrative ballads (“La Maguinita” and “Jesusita”), the Communist anthem (“L’Internationale”), Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony, and Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde. And “Spanish speakers might also listen for the rhythm of a familiar Mexican curse growling in the trombone as Lupe (Diego’s former wife) insults Frida and Diego at their wedding.”

The orchestra continues its ironic commentary throughout the work. Two examples: as Frida and Diego quarrel about their mutual infidelities, the brass offer a snarling version of the tender Act I love music, “Niía de mi corazon” (Child of my heart); and as Frida’s death figures (calaveras) recreate her self-portrait, as the wounded “Little Deer,” in an affecting ballet sequence, Frida is stabbed, both physically (by the arrow) and musically (by piercing orchestral repetitions of Diego’s demand for a divorce, “You don’t need me anymore”).

Deeper musical characterization is achieved through the extensive use of vocal ensembles. Rodríguez says, “You learn much more about people by watching them not alone, but in conflict with others. Frida and Diego have two powerful love scenes, one at the beginning and one at the end, with one fight after another in between. It’s that fascinating and unpredictable through-line of their relationship that drives the action.” The demanding role of Frida requires not only extensive monologues, both spoken and sung, but also duets, trios, quartets, a quintet, sextet and several larger ensembles, working up to an intricate nine-part “layer-cake samba finale.” In a musical metaphor for Frida’s unique persona, her vocal line is scored with its own characteristic rhythms: often in three-quarter time while the orchestra or the rest of the cast is in duple meter. As Rodríguez observes, ”Frida sings as she lived—against the tide from the very first note.”

Photos

Have accordion, will travel! Checking in at the San Diego airport (September 23, 2019).

Henry and saxophone/clarinet player John Warren at the first orchestra rehearsal of Frida at the Atlanta Opera rehearsal hall (September 24, 2019).

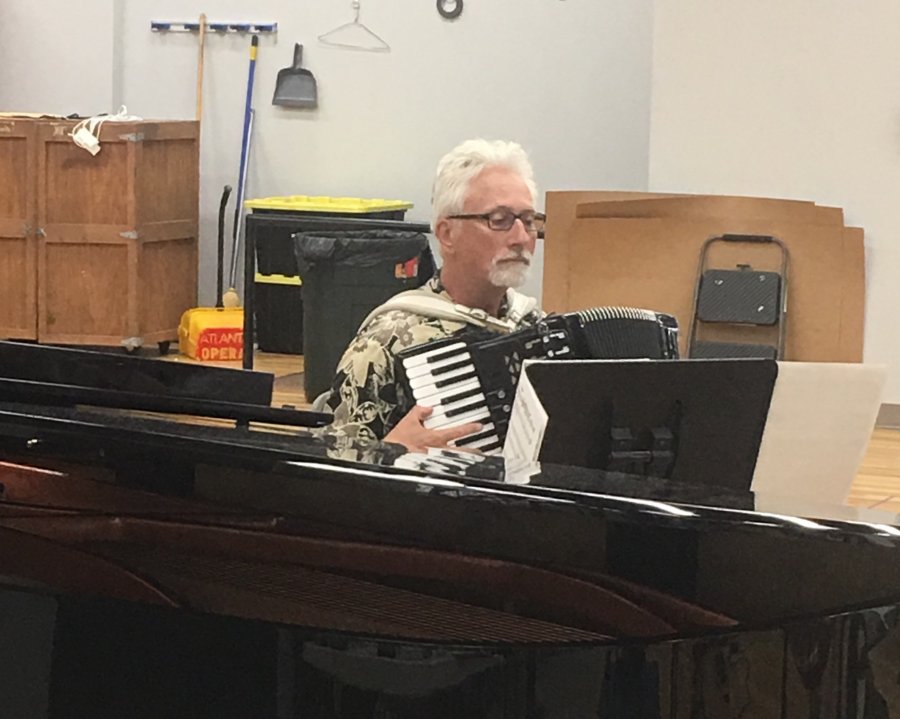

In rehearsal at the Atlanta Opera rehearsal hall (September 24, 2019).

Musicians in rehearsal at the Atlanta Opera rehearsal hall (September 24, 2019).

Musicians in rehearsal at the Atlanta Opera rehearsal hall (September 24, 2019).

Maestro Jorge Parodi and Henry examine the score in a practice room at the Atlanta Opera rehearsal hall (September 25, 2019).

Maestro Jorge Parodi and Henry at the Atlanta Opera rehearsal hall (October 4, 2019).

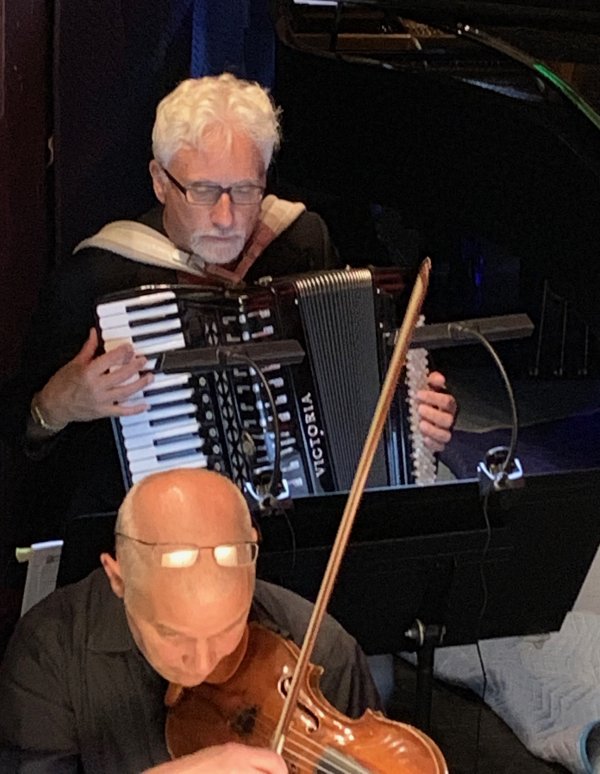

Henry and Atlanta Opera Orchestra Concertmaster/first violinist Peter Ciaschini warming up in the pit on opening night (October 5, 2019).

Maestro Jorge Parodi and John Warren in the pit on opening night (October 5, 2019).

Pianist Paul Schwartz, Henry, violinist Peter Ciachini, violist William Johnston, and cellist Charae Krueger warming up in the pit on opening night (October 5, 2019).

Mezzo-soprano Catalina Cuervo played Frida Kahlo. Known as the “Fiery Soprano,” Colombian born Catalina Cuervo holds the distinction of having performed the most productions of Piazzolla’s Maria de Buenos Aires in the world in the history of the opera.

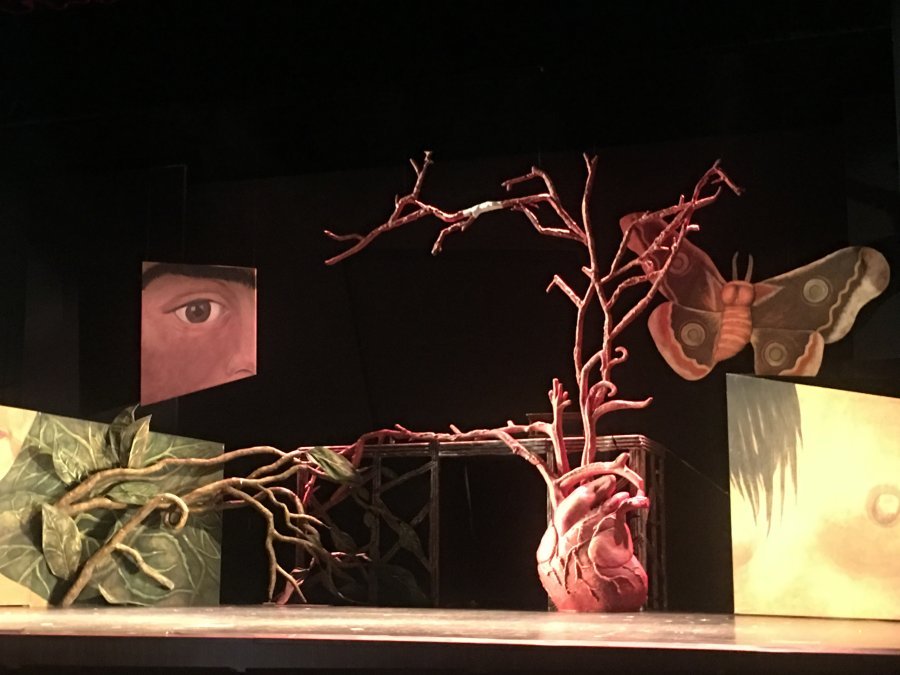

The set.

The wedding reception scene.

Opening night. I heard the performance was sold out. Later, I found that the last show was also sold out. (October 5, 2019).

Bows. Maestro Jorge Parodi acknowledges the Atlanta Opera Orchestra in the pit. (October 5, 2019).

Bows. (October 5, 2019).

At the cast party: Maestro Jorge Parodi, mezzo-soprano Catalina Cuervo, and Henry.

At the cast party: Accordionist Suzana Beites (who flew in from New Jersey to see the show), mezzo-soprano Catalina Cuervo, and Henry.

At the cast party: Mark McConnell, Personel Manager and principal trombonist for the Atlanta Opera, Mark’s wife Margie, Henry and Suzana Beites.

At the cast party: Maestro Jorge Parodi and Henry in discussion.