The Guru, Mayavadins, and Women

Tracing the Origins of Selected Polemical Statements in the Work of A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami

Ekkehard Lorenz

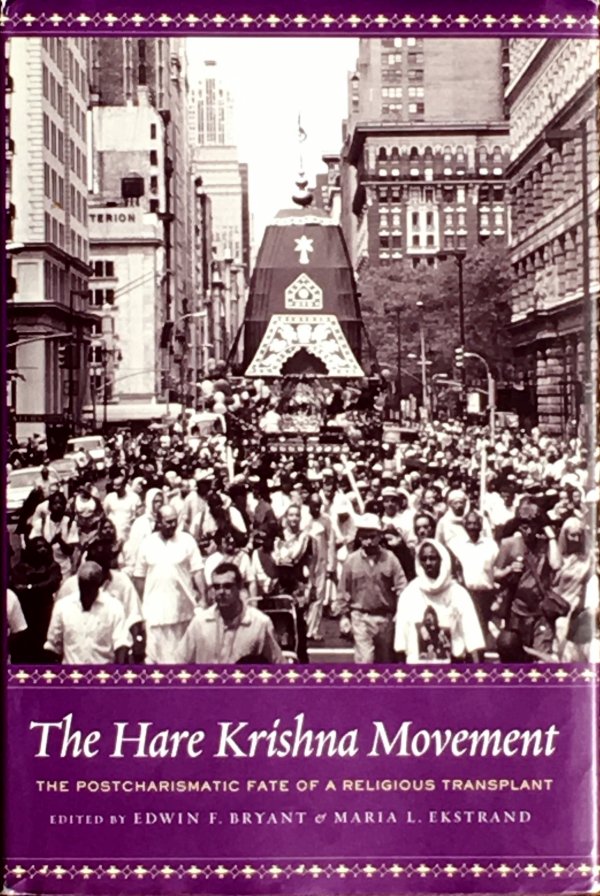

A chapter from:

The Hare Krishna Movement—The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant

Edited by Edwin F. Bryant and Maria L. Ekstrand

Columbia University Press (2004)

In 1965, Bhaktivedanta Swami, a retired pharmaceutical manufacturer from Calcutta, moved to New York where he founded the International Society for Krishna Consciousness. In the following years he published his English translations of and commentaries on the Bhagavad Gita and the Bhagavat Purana. By paraphrasing the words of and repeatedly referring to the earlier Gaudiya Vaishnava writers in his books and lectures, he popularized these authors—perhaps for the first time—among a large English speaking audience outside of India. While these earlier commentators, in their writing, remained strictly within the boundaries of scriptural context, often limiting their notes to clarifications of syntax, grammar, and word meanings, with occasional quotes from other scriptures, Bhaktivedanta Swami added his own urgent and personal message. The contemporary world economy, politics, social development, education, and racial and gender issues are not uncommon topics in his commentaries. And while the works of his predecessor commentators had always remained reading matter for an elite minority, he wanted his books to be translated into all the languages of the world and distributed profusely.

Bhaktivedanta Swami’s work is neither text-critical nor systematic. He basically drew from whatever sources happened to be easily available to him at the time. For his English translations of his Bhagavat Gita As It Is,1 he relied to a large extent on Dr. Radhakrishnan’s English Gita translation.2 His English translation of the Bhagavat Purana is based on a number of different sources. In his translation of the third book,3 for example, there are a large number of stanzas that agree verbatim with C. L. Goswami and and M. A. Sastri’s earlier English translation of the text.4 While Bhaktivedanta Swami continued to use their work when he translated the fourth book,5 he no longer copied any of their translations verbatim. From the twenty-eighth chapter of book 4 to the thirteenth chapter of book 10,6 his work is clearly based on the Gaudiya Math Bengali edition of Bhagavat Purana.7 Many of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s translations in this part of his work are not rendered directly from the original Sanskrit, but from this Bengali translation.8 His books, however, nowhere state the actual sources on which they are based.

Many explanations in Bhaktivedanta Swami’s commentary on the Bhagavat Purana can be traced directly to the traditional Gaudiya Sanskrit commentaries that he used. It appears that in order to formulate his own commentary on a given stanza of the Bhagavat Purana, he would first glance at the notes of two or three of the earlier commentators, paraphrase fragments of their glosses, and then add his own elaborations.9 He called his commentaries “Bhaktivedanta Purports” and often suggested that they had not been written by himself, but that God, Krishna, had revealed them to him.10 For the Bhagavat Purana alone, he produced 5,800 purports averaging 250 words in length.11

Not everything in the purports builds from the previous commentaries. There are many passages wherein Bhaktivedanta Swami clearly presents his own views—for example, when he dismisses the reports of the Moon landing in 1969,12 debates scientific theories like Darwin’s theory of evolution,13 or condemns contemporary culture and morals when discussing the miniskirt fashion.14 While it is easy to identify these statements as the author’s own opinions, Bhaktivedanta Swami’s purports also contain a range of statements that sound as if they were the conclusions of the earlier commentators, but turn out to be his personal contributions when one compares them to all the commentaries that he possibly could have used.

To explore this aspect of Bhaktivedanta’s commentaries, a list of about 150 frequently recurring keywords in the Bhaktivedanta purports (such as varna, brahmana, “scholars,” “women,” “Mayavadis,” etc.) was drawn up. Then, purport after purport was analyzed to see how many, and which, of those keywords corresponded to words in the traditional commentaries on the same stanzas. This procedure was repeated with all the purports to the Bhagavat Gita and 664 purports to the Bhagavat Purana,15 with a view to eliminating those keywords that were common to both the purports and the traditional commentaries. As a result, a shorter list emerged of just those keywords that rarely or never had synonymous or equivalent expressions in any of the corresponding earlier commentaries. These fall into three distinct categories: statements about the position of the guru or spiritual master, statements about impersonalists or Mayavadins, and statements about women and sex.

THE POSITION OF THE GURU

Much of what Bhaktivedanta Swami writes about the guru repeats traditional Hindu views and is based on well-known Upanishadic statements that he either quotes or paraphrases: yasya deve para-bhaktih (Shvetasvatara 6.23), tad-vijnanartham sa gurum evabhigacchet (Mundaka 1.2.12), and acharyavan purusho veda (Chandogya 6.14.2). While the earlier commentaries occasionally quote these aphorisms, Bhaktivedanta Swami employs them significantly more often, especially to underline the absolute position, superhuman qualities, and overall importance of the guru. The three above-mentioned passages, for example, appear 53 times in his purports, but only 12 of these occurrences have corresponding passages in earlier commentaries.

In the purports of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s Bhagavat Gita alone, there are 138 statements about the spiritual master, but only in 24 of the cases did an earlier commentator refer to an equivalent word or concept.16 In his purports to the second book of the Bhagavat Purana,17 Bhaktivedanta Swami makes 141 statements about the position and importance of the guru, but only 7 of those statements can be linked to the commentaries on which his work is based.18 The topic is clearly important to him. If the data from the Gita and the second book are representative, perhaps 89 percent of what he writes about the spiritual master’s position and qualifications is not based on statements that earlier commentators made in the same context.

Given this unprecedented emphasis, it seems useful to consider how Bhaktivedanta Swami understood the role of the guru. He especially emphasizes how a person without a guru cannot know God:

Only Lord Krishna, or His bona fide representative the spiritual master, can release the conditioned soul.19

For one who does not take personal training under the guidance of a bona fide spiritual master, it is impossible to even begin to understand Krishna.20

Unless one is in touch with a realized spiritual master, he cannot actually realize the real nature of self.21

Time and again, Bhaktivedanta Swami also insists that the spiritual master be bona fide:

A bona fide spiritual master does not mention anything not mentioned in the authorized scriptures.22

A bona fide spiritual master is he who has received the mercy of his guru, who in turn is bona fide because he has received the mercy of his guru.23

I am successful in my teaching work because I have not deviated one inch from my Spiritual Master’s instruction.24

Moreover, he frequently states that, to be bona fide, the guru must be situated in the disciplic succession (guru parampara). In the introduction to his Bhagavat Gita, in his purports, and in letters to his disciples, he lists the names of the gurus in the disciplic succession, beginning with Krishna and ending with himself.

Elsewhere, Bhaktivedanta Swami repeatedly speaks about the guru’s role as an educator; hence the name gurukula (house of the guru), which he gave to a network of boarding schools he created for ISKCON children.

Everyone, and especially the Brahmin and Ksatriya, was trained in the transcendental art under the care of the spiritual master far away from home, in the status of brahmacharya.25

Children at the age of five are sent to the guru-kula, or the place of the spiritual master, and the master trains the young boys in the strict discipline of becoming brahmacharis.26

As soon as the children are a little grown up, they are sent to our Gurukula school in Dallas, Texas, where they are trained to become fully Krishna conscious devotees.27

Bhaktivedanta Swami also envisions the guru’s role as family instructor:

Any member of the family who is above twelve years of age should be initiated by a bona fide spiritual master, and all the members of the household should be engaged in the daily service of the Lord, beginning from morning (4 a.m.) till night (10 p.m.).28

Perhaps the most important mission of the guru—judging by the extent Bhaktivedanta Swami dwells on this topic—is to teach men about women and sex:29

During the first stage of life, up to twenty-five years of age, a man may be trained as a brahmacari under the guidance of a bona fide spiritual master just to understand that woman is the real binding force in material existence.30

His interpretation of Bhagavat Purana 7.12.1 illustrates that according to him, the guru exerts complete control of his married male disciple’s sexual activities:

If the spiritual master’s orders allow a grihastha to engage in sex life at a particular time, then the grihastha may do so; otherwise, if the spiritual master orders against it, the grihastha should abstain. The grihastha must obtain permission from the spiritual master to observe the ritualistic ceremony of garbhadhana-samskara. Then he may approach his wife to beget children, otherwise not. A Brahmin generally remains a brahmacari throughout his entire life, but although some Brahmins become grihasthas and indulge in sex life, they do so under the complete control of the spiritual master.31

None of the earlier commentators32 has explained that Bhagavat Purana passage in this way. In fact, both Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati and Ganga-sahaya took the word “guru” in this verse to mean family elders, who advise the newly-married boy about the proper time for begetting offspring.

Lecturing about the same topic before disciples in Bombay in 1976, Bhaktivedanta Swami claimed that Viraraghava Acharya, a fourteenth century Bhagavat commentator, had expressed equally strong views regarding gurus, sex and householders:

If a married man stick to one wife, and before sex, if he takes permission from his spiritual master, then he is brahmacari. Not whimsically. When the spiritual master orders him that “Now you can beget a child,” then he is brahmacari. Srila Viraraghava Acharya, he has described in his comment that there are two kinds of brahmacari. One brahmacari is naisthika-brahmacari; he doesn’t marry. And another brahmacari . . . [a]lthough he marries, he is fully under the control of the spiritual master, even for sex. He is also brahmacari.33

However, the Sanskrit commentary Bhaktivedanta Swami refers to does not state that a married man remains fully under control of the spiritual master. That commentary just names the two classes of celibate students, and explains that before one becomes a householder, anchorite, sannyasin, or even a life-long celibate, one is known as upakurvanaka, a celibate who still has an option to marry.34

From these and other statements that Bhaktivedanta Swami makes about the guru, it appears that he envisions the master as an all-knowing, all-competent spiritual autocrat: a person without whose mercy the devotee is doomed, who is beyond criticism, and who exercises total control over the lives of his disciples. Bhaktivedanta Swami’s statements about the position of the spiritual master take on special relevance since, in matters of epistemological conflict, his views are deemed ultimate, even over scripture, the traditional source of highest authority (see Conrad Joseph’s essay in this volume).

MAYAVADINS

Another topic that received extensive coverage in Bhaktivedanta Swami’s writings is what he calls “impersonalism” or “Mayavada philosophy.” It is, however, not so much the philosophy he discusses but rather its proponents, the Mayavadins, or “impersonalists,” as he calls them. He frequently describes them as foolish, less intelligent, or ignorant:

The self-centered impersonalists, by their gross ignorance, accept the Lord as one of them.35

The foolish impersonalists still maintain that the Lord is formless.36

The less intelligent impersonalists cannot see the Supreme.37

In his purports to the Bhagavat Purana, Bhaktivedanta Swami makes more than 600 statements about Mayavadins and impersonalists. None of the 402 statements that are found in the second, third and fourth books alone (which were examined for this essay), nor any of the 85 statements he makes about impersonalists and Mayavadins in his Bhagavat Gita, can be traced back to the earlier commenters in the tradition.

While none of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s statements about impersonalists in the above-mentioned sources can be traced to the sources he worked from, it can be shown that many of these statements were his passionate responses to expressions he found in the English source material on which his translations were based. For example, in his purport to Bhagavat Gita 8.3, he states:

Impersonalist commentators on the Bhagavad-gita unreasonably assume that Brahman takes the form of jiva in the material world, and to substantiate this they refer to Chapter Fifteen, verse 7 of the Gita.38

It was Dr. Radhakrishnan who, in his edition (1948) of the Gita, commented: “svabhava: Brahman assumes the form of jiva, Chapter 15, 7).”39

Another example of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s dialogue with modern English commentaries is in his purport to Bhagavat Gita 9.11:

Some of those who deride Krishna and who are infected with the Mayavadi philosophy quote the following verse from the Shrimad-Bhagavatam (3.29.21) to prove that Krishna is just an ordinary man.40

Again it is Radhakrishnan who wrote, commenting on the same passage from the Gita:

In the Bhagavat, III, 29, 21, the Lord is presented as saying, “I am present in all beings as their soul but ignoring My presence, the mortal makes a display of image worship.”41

Thus Bhaktivedanta Swami’s unnamed Mayavadin turns out to be Dr. Radhakrishnan.

It is not that Bhaktivedanta Swami was interested in Radhakrishnan’s work or philosophy, but he apparently considered Radhakrishnan’s English Gita a useful help in his own translation work. This is documented in the following passage from Hayagriva Dasa’s work, The Hare Krishna Explosion:42

Swamiji finally tires of my consulting him about Bhagavad-gita verses. “Just copy the verses from some other translation,” he tells me, discarding the whole matter with a wave of his hand. “The verses aren’t important. There are so many translations, more or less accurate, and the Sanskrit is always there. It’s my purports that are important. Concentrate on the purports. There are so many nonsense purports like Radhakrishnan’s and Gandhi’s, and Nikhilananda’s. What is lacking is these Vaishnava purports in the preaching line of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. That is what is lacking in English. That is what is lacking in the world.”

“I can’t just copy others,” I say.

“There is no harm.”

“But that’s plagiarism.̵

“How’s that? They are Krishna’s words. Krishna’s words are clear, like the sun. Just these rascal commentators have diverted the meaning by saying ‘Not to Krishna.’ So my purports are saying ‘To Krishna.’ That is the only difference.”

The translations of many stanzas of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s first edition of his Bhagavat Gita seem to have been adapted from Radhakrishnan’s translation. When Bhaktivedanta Swami, in his translating work, came across passages in that book that didn’t fit his own views, he produced vigorous attacks on “certain Mayavadins,” who always remained unnamed.

A similar pattern can be found in the third and fourth books of the Bhagavat Purana. The English translations of many stanzas in Bhaktivedanta Swami’s third book agree verbatim with the corresponding stanzas in the English Gita-Press edition by C. L. Goswami and M. A. Sastri. In a letter to a disciple, dated 21 December 1967, Bhaktivedanta Swami wrote:

Please send me the third canto English translation of the Shrimad-Bhagavatam done by the Gita Press. You got these copies from the Gita Press for reference. I want the third canto, please send as soon as possible.43

When one compares the English translations of the stanzas in chapters 14 to 31 in Bhaktivedanta Swami’s third book to those of the Gita Press English edition,44 one finds not only stanzas which have been copied verbatim but also a substantial number of stanzas that have been modified only slightly. Original translations are rare. By conservative estimation, up to 50 percent of the English translations in Bhaktivedanta Swami’s rendition of the third book were actually copied from the Gita Press edition. Considering the following excerpt from a letter that Bhaktivedanta Swami wrote to a disciple, one wonders why he chose to copy so much of the Gita Press translation, if he thought that it was so “full of Mayavada philosophy”:

Gita Press is full of Mayavada philosophy which says Krishna has no form but He assumes a form for facility of devotional service. This is nonsense. I am just trying to wipe out this Mayavada philosophy and you may not therefore order for any more copy of the English Bhagavatam published by the Gita Press. The one which you have got may be kept only for reference on having an understanding of the Mayavada Philosophy which is very dangerous for ordinary persons.45

Incidentally, the purports to the third book contain more criticism of Mayavadins than any other part of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s Bhagavat Purana. Apparently he reacted to Sastri and Goswami’s interpretations of certain key terms. For example, in his purport to Bhagavat Purana 3.29.33, he writes:

Sometimes Mayavadi philosophers, due to a poor fund of knowledge, define the word sama-darshanat to mean that a devotee should see himself as one with the Supreme Personality of Godhead. This is foolishness.46

Sastri and Goswami had indeed translated sama-darshanat (in Bhagavat Purana 3.29.33) as: “thus sees no difference between himself and Me.”47

Anti-Mayavadin rhetoric in the purports to the fourth book of the Bhagavat Purana can also be accurately traced back to Sastri and Goswami’s interpretation of certain keywords that caused Bhaktivedanta Swami to strongly disagree. For example, in his purport to 4.22.25, he notes:

The word brahmani used in this verse is commented upon by the impersonalists or professional reciters of Bhagavatam, who are mainly advocates of the caste system by demoniac birthright. They say that brahmani means the impersonal Brahman.48

Here, too, Sastri and Goswami had rendered brahmani as “the attributeless Brahma.”49 The same authors (i.e., Radhakrishnan, Sastri and Goswami) of whose translations Bhaktivedanta Swami had availed himself became the targets of his numerous polemical remarks regarding their understanding of spirituality.

The large number of statements about Mayavadins that are found in the Bhaktivedanta purports to the Gita and the Bhagavat Purana, and the type and quality of these statements, have no precedent in the works of the earlier Gaudiya commentators.50 There is, however, a certain tradition of dispute and debate with Mayavadins that can be seen in the Chaitanya Charitamrita, a chiefly Bengali hagiography of Chaitanya written by Krishnadas Kaviraja in 1615. Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati, Bhaktivedanta Swami’s guru, had written a Bengali commentary, the Anubhashya, on Krishnadas’s work, in which he does elaborate on Mayavadins and impersonalists, Buddhists, Tattvavadins, sahajiyas, and other groups that were considered deviant or inimical to Gaudiya Vaishnavism, but these are topics that Krishnadas himself develops in his book. In his commentary on the Bhagavat Purana, however, the same Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati rarely mentions Mayavadins. Following the earlier tradition, he keeps closely to the subject of the text under discussion.

Gaudiya Vaishnavas consider that the nucleus of the entire Bhagavata and its philosophy is found in four stanzas (chatuh shloki) in the second book of the Bhagavat Purana.51 With reference to these four important verses, Bhaktivedanta Swami writes:

The impersonal explanation of those four verses in the Second Canto is nullified herewith. Sridhara Svami also explains in this connection that the same concise form of the Bhagavatam concerned the pastimes of Lord Krishna and was never meant for impersonal indulgence.52

Here Bhaktivedanta claims that the famous fourteenth-century author Shridhara Swamin wrote in his Bhavartha-dipika commentary to Bhagavat Purana 3.4.13 that the chatuh shloka were “never meant for impersonal indulgence.” In other words, he claims that Shridhara had formulated attacks against Mayavadins that were just as polemical as his own. In fact, Shridhara Swamin did not write this.53 Never, in his entire commentary on the Bhagavat Purana, does Shridhara Swami mention “impersonal indulgence” or Mayavadins, not to speak of condemning the latter.

While it might be argued that this is an isolated example, it has far-reaching implications. One wonders why Bhaktivedanta Swami went so far as to tell his readers that Shridhara Swamin condemns impersonalist philosophy, when the fact is not only that Shridhara did not do this, but it is he, out of all the Bhagavata commentators, of whom it may be said that he had impersonalist leanings.54 Could it be that Bhaktivedanta Swami was seeking to invest his statements with the authority of Shridhara Swamin, who is widely respected as the foremost Bhagavata commentator? This question is especially difficult to answer because Bhaktivedanta Swami never worked with competent Sanskrit editors, and it is hard to determine to what degree he was aware of such misrepresentations. What is known is that he repeatedly criticized or dismissed many of his disciples who gradually achieved a certain level of proficiency in Sanskrit.55 Since anti-Mayavadi polemics are highly conspicuous in ISKCON discourses (see also K. P. Sinha, A Critique of A. C. Bhaktivedanta [Calcutta, 1997]), a thorough investigation into what caused Bhaktivedanta Swami to formulate so many aggressive attacks on this group might help create a better understanding of his teachings and his movement.

WOMEN AND SEX

There is, within the Hare Krishna movement, a general awareness that Bhaktivedanta Swami made a large number of controversial statements about women. Some were written statements in his commentaries on the canonical Vaishnava scriptures, others were spoken statements in his lectures and conversations. While there is a general feeling that Bhaktivedanta Swami did not always mention pleasant things about women, an accurate assessment of how much of what he said was favorable and how much was unfavorable has never been presented.

A quantitative and qualitative analysis of all statements regarding women that Bhaktivedanta Swami made in his purports to the Bhagavad Gita and in his purports to five chosen books56 of the Bhagavat Purana is presented below. Each of his 510 statements has been assigned to one of the following six categories:

1. Statements about women’s sexuality and men’s views of women as sex objects or sexually agitating objects that need to be avoided, e.g.: “women are always dressed in an overly attractive fashion to victimize the minds of men.”57

2. Statements about women’s qualities, e.g.: “It may be clearly said that the understanding of a woman is always inferior to the understanding of a man.”58

3. Statements about women as belonging to a certain class or social group, e.g.: “Women, Shudras and even birds and other lower living entities can be elevated to the Achyuta-gotra.”59

4. Statements about restrictions governing women, e.g.: “The woman must remain at home.”60

5. General statements where “woman” simply means a person of the female gender, with no description or value judgment: “All over the world there are millions and billions of men and women.”61

6. Other types of statements: “A barren woman cannot understand the grief of a mother.”62

The analysis further ascertained whether any of the earlier commentators mentioned anything about women within the same scriptural context.

Eighty percent of all statements that Bhaktivedanta Swami makes about women in the six works investigated are negative statements, in the sense that they involve restrictions, list bad qualities, group women in socially inferior classes, or treat them as sex objects that have to be avoided. The figure of 80 percent is constituted as follows:

56% of all statements concern women as sex objects

8% are statements about women’s class, status, or position

9% are restrictions that state that women should not be given any freedom

7% are statements about women having bad qualities

While “qualities” statements actually comprise 15 percent of the total, with half of them referring to “good” qualities, these are only mentioned in connection with specific women who are prominent figures in Hindu mythology: Kunti, Draupadi, Gandhari, and Sati. “Women in general,” in other words, present-day living women, are only mentioned as having bad qualities.

For the Bhagavad Gita there are 7 out of 39 statements about women that can be related to the earlier commentaries; for the first book of the Bhagavata Purana, 12 out of 117 can be so related; for the second book, 4 out of 37; and for the eighth book, 16 out of 52. This means that 80 percent of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s statements about women, in the purports to these four titles, are his own contributions that do not represent statements that earlier commentators made in the same context. Reasonably similar results can be expected for the titles that were not included in this study.

While Bhaktivedanta Swami often made generalizing statements regarding Mayavadins,63 he issued even more such broad generalizations about women:

Generally all women desire material enjoyment.64

Women in general should not be trusted.65

Women are generally not very intelligent.66

It appears that woman is a stumbling block for self-realization.67

Other statements that are not supported by the earlier commentators are Bhaktivedanta Swami’s views on rape:

Although rape is not legally allowed, it is a fact that a woman likes a man who is very expert at rape.68

When a husbandless woman is attacked by an aggressive man, she takes his action to be mercy.69

Generally when a woman is attacked by a man—whether her husband or some other man—she enjoys the attack, being too lusty.70

While sexuality is a topic that mainly comes up when Bhaktivedanta Swami focuses on women, he comments not only on their sexual morals but also on those of the Mayavadins:

The answer anticipates the abominable acts of the Mayavadi impersonalists who place themselves in the position of Krishna and enjoy the company of young girls and women.71

In general, he depicts both groups as less intelligent, inferior, sexually incontinent, and downright dangerous.

In conclusion, then, since the historical and prolonged abuse of women in ISKCON has by now been acknowledged even by the most conservative elements in the movement, a more systematic analysis of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s statements about women and sex might be worthwhile, leading to a deeper and better understanding of the problem. ISKCON’s polemical dismissal of other Hindu groups perceived to espouse “Mayavadin philosophy” (which includes almost every other Hindu group established in the West) is also an inherent part of ISKCON’s self-definition and ethos that few would deny.72 As Bhaktivedanta Swami was the founder of ISKCON, his derogations of Mayavadins and women and sex, coupled with his exaltations of the spiritual master, are not irrelevant to the attitudes demonstrated by his disciples. Since his statements in these areas have no parallel in the writings of his predecessor commentators, one is therefore led to search for links in his personal experiences. However, this research, and the question of how his views influenced his followers, falls under the academic rubrics of sociology or psychology of religion, rather than that of traditional Sanskrit commentarial exegesis.

Bhaktivedanta Swami’s statements in the three areas treated here, namely the guru’s position, Mayavadins, and women and sex, are bound to leave a certain impression on his readers. If the frequency of a particular type of statement exceeds a certain magnitude, then the context in which each particular statement appears loses relevance. What remains is the overall impression created by the sheer number of repetitions. In this particular case, that impression might very well be: the spiritual master is good, beyond sexuality, and superior to all; Mayavadins are dangerous and bad; women and sex are dangerous and bad. Within the Hare Krishna movement, Bhaktivedanta Swami’s purports are considered as good as, and in case of conflict, superior to, scripture. History shows that the general mass of his followers indeed imbibed and lived by these ideas he conveyed.

END NOTES

1. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Bhagavad-Gita As It Is, 2nd ed. (Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1980).

2. S. Radhakrishnan, The Bhagavadgita: With an Introductory Essay, Sanskrit Text, English Translation and Notes (1948: reprint, Delhi: HarperCollins Publishers India, 1993).

3. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad-Bhagavatam: Third Canto, 2 vols. (Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1987).

4. C. L. Goswami and M. A. Sastri, ed. and trans., Bhagavata Purana. SrimadBhagavata Purana, 2 vols. Gorakhpur: Gita Press, 1971). (Gita Press had published this translation in multiple volumes already before 1967.)

5. See my discussion of his “polemic” against Sastri and Goswami below (section on Mayavadins), referenced by notes 48 and 49.

6. From book 4, chapter 28 of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s translation of the Bhagavata Purana up to chapter 13 of book 10 (a total of 125 chapters), the breaking up of the sloka-padas of the original Sanskrit text into numbered stanzas shows 100 percent agreement with the Gaudiya Math edition (see next note). The same errors (Sanskrit spelling errors, misplaced paragraphs, etc.) that occur in the Gaudiya Math edition are also found in Bhaktivedanta Swami’s text.

7. Srimad-Bhagavatam, Srimad-Gaudiya-bhashyopetam, 2nd edition, 12 vols. (Mayapur: Sri Chaitanya Math, 1962-69).

8. Explanatory notes that occur in the Gaudiya Math Bengali translation in parentheses often appear without parentheses in Bhaktivedanta Swami’s English translations (as if they were part of the original Sanskrit text). Bhaktivedanta Swami’s translation of Bhagavata Purana 5.25.3, for example, contains such as passage: “He is always in the transcendental position, but because He is worshiped by Lord Siva, the deity of tama-guna or darkness, He is sometimes called tamasi” A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad-Bhagavatam: Fifth Canto [Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1987], 872). The note in the Bengali edition reads: “ei murti vastutah visuddha-sattva-ay, tamogunavatara rudrera antare thakiya samhara-karyadi karena baliya ai murtike tamo-mayi bala haiyache” (Srimad-Bhagavatam, pancama-skandha-matram [Mayapur: Sri Chaitanya Math, 1969], 1802).

9. “No, no. I am taking help from all these Gosvamis and giving a summary.” Interview with Professors O’Connel, Motilal, and Shivarama, June 18, 1976, Toronto, The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, Sandy Ridge, NC: Bhaktivedanta Archives, 1995, record 499981.

10. “Sometimes I become surprised how I have written this. Although I am the writer, still sometimes I am surprised how these things have come. Such vivid description. Where is such literature throughout the whole world? It is all Krishna’s mercy. Every line is perfect.” The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, Talk about Varnashrama, S.B. 2.1.1-5, June 28, 1977, Vrindavana, record 561940.

“I have tried to explain what is there in the Bhagavatam, expand it. That is not my explanation, that is Krishna’s explanation. I cannot explain now. That moment I could explain. That means Krishna’s . . . I can understand that. That the description is very nicely given. Although it is my writing, but I know it is not my writing. It is Krishna’s writing.” The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, Room conversation, September 4, 1976, Vrindavana, record 523163.

11. Bhaktivedanta Swami translated and commented up to chapter 13 of the tenth book of the Bhagavata Purana. The remaining 5,311 stanzas have been translated by his disciples, who also produced commentaries on 2,991 of these stanzas, trying to emulate, as far as possible, the style and spirit of their guru.

12. “Recently they have said that they have gone to the moon but did not find any living entities there. But Srimad-Bhagavatam and the other Vedic literatures do not agree with this foolish conception.” Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam: Seventh Canto (Los Angeles, Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1987), 804.

13. “Darwin’s theory stating that no human being existed from the beginning but that humans evolved after many, many years is simply a nonsensical theory.” Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam: Fourth Canto, 2:658.

14. “Kasyapa Muni advised his wife not to go out onto the street unless she was well decorated and well dressed. He did not encourage the miniskirts that have now become fashionable.” Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam, Sixth Canto, 832.

15. Purports from all ten books of the Bhagavata Purana have been analyzed. The number of each book from the Bhagavata Purana (from book 1 to book 10) is: 66, 121, 198, 130, 17, 9, 67, 29, 12, 15. These are all the purports where any given keyword turned up, with the exception of several cases where the purport contains a keyword but says nothing specific about it.

16. For his own commentaries on the Gita, Bhaktivedanta Swami had mainly relied on Baladeva Vidya-Bhusana, a Vaishnava writer from Orissa, who lived during the first half of the eighteenth century. His Sanskrit commentary on the Bhagavad Gita, the Gita Vibhushana-Bhashya, is the source of 22 guru statements in the Bhagavad Gita. Two statements can be traced to Vishvanatha Chakravartin, the seventeenth century Vaishnava author of Sarartha-varshini-tika. Both commentaries have been published in Baba Krishnadasa, ed., Srimadbhagavatgita (Mathura: Vik. Sam.), 2023.

17. The second book of the Bhagavata Purana is the shortest (391 numbered stanzas). Yet, in the 356 purports in which Bhaktivedanta Swami commented in this book, there occur more statements about the position and importance of the guru than in his purports in any other book. Like the Gita, this is one of the first books he wrote after coming to the West.

18. The following eighteen commentaries on the Bhagavata Purana were available to Bhaktivedanta Swami:

19. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Bhagavad-Gita As It Is, 7.14 purport, 383.

20. Ibid., 11.54 purport, 603.

21. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam, Second Canto, 2.3.1 purport, 136.

22. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam, Fourth Canto, 4.16.1 purport, 1:714.

23. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam, Eighth Canto, 8.16.24 purport, 556.

24. Letter to Brhaspati, Delhi, 17 November, 1971, the Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, record 594392.

25. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam, Second Canto, 2.2.30 purport, 116.

26. Bhaktivedanta, Bhagavad-Gita As It Is, 6.13-14 purport, 322.

27. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, The Nectar of Instruction (Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1975), 7.

28. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam, Second Canto, 2.3.22 purport, 170.

29. Women and sex are prominent topics in Bhaktivedanta Swami’s purports, lectures and conversations. No fewer than 50 passages in his purports mention that a guru must teach about these topics. Sex is mentioned in more than 300 purports; it appears more than 1,200 times in lectures and more than 1,000 times in conversations.

30. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam, Second Canto, 2.7.6 purport, 369.

31. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam, Second Canto, 7.12.1 purport, 690.

32. Here and in all other places where the expression “none of the earlier commentators” is used, it refers to the eighteen commentaries listed above.

33. Lecture Srimad-Bhagavatam 7.12.1, Bombay, 12 April 1976, The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, record 364741.

34. “tatra garhasthyadivan naishthikam apy aupakurvana-purvakam eveti darshayitum tavad aupakurvana-brahmacharya-dharmma uchyante” (Bhagavata-chandrika, 7.12.1), Shrimad-Bhagavata-mahapuranam: saptamam skandham, ed. Krishnasankarah Sastri Sola: Sri Bhagavata-Vidyapithah, 1968, 441.

35. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam, Second Canto, 2.5.24 purport, 266.

36. Bhaktivedanta, Bhagavad-Gita As It Is, 7.24 purport, 402.

37. Ibid., 7.25 purport, 404.

38. Ibid., 8.3 purport, 417.

39. Radhakrishnan, The Bhagavadgita, 227.

40. Bhaktivedanta, Bhagavad-Gita As It Is, 9.11 purport, 469.

41. Radhakrishnan, The Bhagavadgita, 243.

42. Hayagriva Dasa, The Hare Krishna Explosion: The Birth of Krishna Consciousness in America 1966-1969 (New Vrindaban, W. Va.: 1985), 210-11.

43. Letter to Rayarama, San Francisco, 21 December 1967, The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, record 580956.

44. The third book comprises 1,411 stanzas and these 18 chapters comprise 804 stanzas.

45. Letter to Rayarama, San Francisco, 7 March 1967, The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, record 580012.

46. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam: Third Canto, 3.29.33 purport 655.

47. Goswami and Sastri, ed. and trans., Bhagavata Purana. SrimadBhagavata Purana, 1:270.

48. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam: Fourth Canto, 4.22.25 purport, 177.

49. Goswami and Sastri, ed. and trans., Bhagavata Purana. SrimadBhagavata Purana, 1:389.

50. Sometimes Madhva, the founder of the Dvaita school, is counted as a Gaudiya Vaishnava. While it is true that Madhva often attacked the Advaita doctrine in his commentaries on the Gita and the Bhagavata Purana, his attacks are far less frequent than and also rather different from Bhaktivedanta Swami’s. In his entire Bhagavata-tatparya-nirnaya (Madhva’s commentary on the Bhagavata Purana), for example, Madhva mentions the Advaita doctrine not more than 30 times explicitly; and on twenty occasions he mentions that those who hold Advaitin views will go to hell. None of these passages is elaborate.

51. Depending on the edition, these stanzas may be BhP 2.9.33-36 (aham evasam . . . to . . . sarvatra sarvada).

52. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam: Third Canto, 3.4.13 purport, 148.

53. Cf. Srimad-bhagavata Shridhari Tika (Varanasi 1988) (reprint of the earlier Nirnaya Sagara Press, Bombay edition); Commenting on the words manmahimavabhasam, Shridhara explained, lila‘vabhasyate yena tat, “that by which my pastimes are illuminated” (195).

54. Commenting on the words tad-brahma-darshanam in BhP 1.3.33, Shridhara wrote: tada jivo brahmaiva bhavatity arthah; katham bhutam; darshanam jnanaika-svarupam. Ibid., 47.

55. “I am practically seeing that as soon as they begin to learn a little Sanskrit immediately they feel that they have become more than their guru and then the policy is kill guru and be killed himself.” ; Letter to Dixit, Vrindaban, 18 September 1976, The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, record 608866.

56. The highest frequency of women- and sex-related statements in Bhaktivedanta Swami’s Bhagavata Purana occurs in his purports to the fourth book. However, in order to sample statements from a larger variety of contexts and to cover a broader interval of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s creative period, books 1, 2, 3, 7 and 8 have been included in this analysis. The first book was written between 1959 and 1964 in India, before Bhaktivedanta Swami came to New York; the manuscripts for books 2 and 3 were produced sometime between 1967 and 1969; book 7 was completed in May 1976, and book 8 in September of the same year. These books thus span Bhaktivedanta’s preaching career and are representative of his views on this matter over the last two decades of his life.

57. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam: First Canto, 1.17.24 purport, 971.

58. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam: Sixth Canto, 6.17.34-35 purport, 786.

59. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam: Seventh Canto, 7.7.54 purport, 407.

60. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam: Third Canto, 3.24.40 purport, 350.

61. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam: Second Canto, 2.3.1 purport, 135.

62. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam: First Canto, 1.7.49 purport, 392.

63. “Generally the impersonalists or monists are influenced by the modes of passion and ignorance.” Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam: Second Canto, 2.1.20 purport, 36.

64. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam: Third Canto, 3.23.54 purport, 299.

65. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam: Eighth Canto, 8.9.9 purport, 330.

66. Bhaktivedanta, Bhagavad-Gita As It Is, 1.40 purport, 67.

67. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam: Second Canto, 2.7.6 purport, 370.

68. Bhaktivedanta, Srimad-Bhagavatam: Fourth Canto, 4.25.41 purport, 478.

69. Ibid., 4.25.42 purport, 479.

70. Ibid., 4.26.26 purport, 542.

71. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Krishna, The Supreme Personality of Godhead: A Summary of Srila Vyasadeva’s Srimad-Bhagavatam, Tenth Canto, rev. ed. (Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1996), 1:315.

72. For recent efforts to redress such tendencies, see Shaunaka Rishi’s position paper, mentioned in Mukunda Goswami and Anuttama’s essay, as ISKCON’s first official statement concerning its relationship with people of other faiths.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

EKKEHARD LORENZ is a student of Indology with focus on medieval and ancient Sanskrit at the Institute for Oriental Languages at the University of Stockholm, Sweden. He was an editorial advisor at ISKCON’s North European Bhaktivedanta Book Trust (BBT), specializing in assisting BBT translators in understanding Bhaktivedanta Swami’s English translations of original Sanskrit texts.

To read Ekkehard Lorenz’s other chapter in The Hare Krishna Movement—The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant, go to Race, Monarchy, and Gender: Bhaktivedanta Swami’s Social Experiment.

UPDATE

Ekkehard Lorenz, Ekanath das, I knew him well, He was a brahmachari living in the temple for around 15 years, then he decided to become scholar, studied Sanskrit, and then followed the oh-so-predictable path of finding faults in guru and param-guru and the books, lost faith, backstabbed them, left the movement and became atheist.

Before being a scholar he was building free energy machines, and it is said he was even trying to build an UFO (but I never saw that).

He thought the homopolar generator, that he found in some underground crackpot magazine, would give more output than you put in, and built one, with big ferrite ceramic magnets. He rotated it at high speed, measured the voltage at the periphery of the copper disc, and thought he had found his free energy source. Jaya. Then the ceramic magnets exploded out of the centrifugal force, turned his hand into a bloody mess, ripped off some fingers, and that was the end to his free energy invention.

He did not read books of science, maybe thinking scientists were demons, or something, I don't know. But if he had, he might have found Faraday's wheel, one of the first electrical machines ever invented.

After that he gave up free energy, and soon he became Sanskrit philosophy scholar instead. That made me very confused—he who was not really into studying books before acting is now the great scholar? The free energy and UFO (?) workshop was very, very secret, and all traces of it was destroyed.

The time in the temple in Sweden was wild and crazy. Not in the child raping way, but in all the crazy things going on there.

Yes he was a disciple of Harikesa, godbrother to me. Harikesa believed that there would be a world war, in 1984, or thereabouts, and everything would turn back to medieval time, so devotees needed free energy to continue book production. He had his own esoteric theory where this free energy come from.

There was also a theory that oil companies intentionally made car engines inefficient to sell more gas, so Ekanath also experimented to build a carburetor so that cars could go ten times the distance on the same amount of fuel. He also experimented with a free energy heating system (based on the water hammer principle, that was supposedly magic) for the farm temple house, that was supposed to give more energy out than you put in. He travelled around the world to all free energy enthusiasts to see how they made it.

Much later he told me that they all were crackpots, and no one had a working system. After ISKCON Ekanath studied and got a degree in Indian philosophy. That is probably when he wrote the scolarly-like articles about Prabhupada and ISKCON and other related things. After that he worked on a computer server center, maintaining computer servers I guess.

Now I think he is retired. In Sweden when you get 65, you stop work and live on state pension. What he does more than that, I don't know.

His wife, a former devotee from East Europe, got a degree in psychology, and works with children, and appears to be a lecturer and an author in the field.

Karolina Prisni Lindqvist

Kramfors, Sweden

Facebook post

March 21, 2025