Race, Monarchy, and Gender

Bhaktivedanta Swami’s Social Experiment

Ekkehard Lorenz

A chapter from:

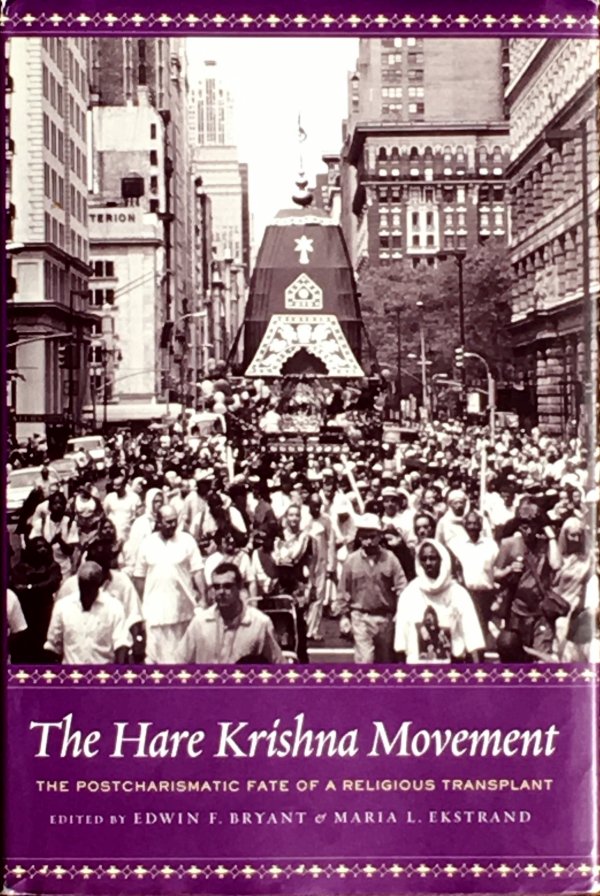

The Hare Krishna Movement—The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant

Edited by Edwin F. Bryant and Maria L. Ekstrand

Columbia University Press (2004)

An Internet search for the string “varnashram dharma” produces more than 450 matches. Today, 50 years after Bhaktivedanta Swami mentioned varnashram for the first time in a public speech, members of the Hare Krishna movement continue to cherish his vision of a perfect society. The majority of matches refer to the sites of organizations that profess allegiance to the teachings of Bhaktivedanta Swami. One such organization, the Bhaktivedanta Archives, introduces their latest book, Speaking About Varnashram, and states:

Criticizing a modern society based on industrialism, materialism, and a callous disregard for the workers who support it, Srila Prabhupada calls for a spiritualized social structure. Citing Bhagavad-gita, he advocates varnashram dharma, a social institution in which people gain spiritual satisfaction and spiritual advancement by doing their daily work as an offering to God.1

Another Web site dedicated to the propagation of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s teachings mentions how varnashram dharma can bring about peace and happiness:

There is a natural system of social organization which can bring about a peaceful society where everyone is happy. This system is described in the timeless Vedic literature of India and it is called Varnashram dharma.2

Apart from mainstream ISKCON, organizations such as the General Headquarters, the Florida Vedic College, and the Bhaktivedanta College all offer extensive varnashram study materials compiled from the teachings of Bhaktivedanta Swami. The Florida Vedic College offers a degree “Master of Arts in Vedic Philosophy,” which includes graduate-level studies of varnashram dharma,3 while the Bhaktivedanta College offers credits for its courses in varnashram dharma and “Applied Varnashram Studies.”4

While there is no consensus within present-day ISKCON regarding what exactly varnashram dharma is, many trust that introducing varnashram principles would improve the health of the movement. The General Headquarters,5 for example, argues that Bhaktivedanta Swami’s mission can only be accomplished by means of vigorous propagation of his varnashram teachings. They especially call for strict implementation of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s teachings regarding women, family, and sexuality in a future Vedic society.6 Many faculty members of the above-mentioned Bhaktivedanta College are also leading members of the General Headquarters. Others, less radical, believe that most of the problems plaguing today’s ISKCON can be traced to its members’ failure to apply varnashram dharma principles in their own lives. While they do not promote the reintroduction of varnashram dharma for the entire world, they call to attention Bhaktivedanta Swami’s instructions to organize ISKCON itself as a varnashram dharma society, so that it might serve as an attractive model. In a recent paper discussing difficulties in the implementation of varnashram dharma in ISKCON, William H. Deadwyler, a leading member of ISKCON’s Governing Body Commission (GBC), states that the foremost problem he and his colleagues are facing is that ISKCON “Has no brain.”7 Like the General Headquarters and the Bhaktivedanta College, he too perceives the solution as an increased and systematic study of the books and teachings of Bhaktivedanta Swami.8

Before exploring in detail what Bhaktivedanta Swami had to say about varnashram dharma, it might be in order to quote a general definition. A. K. Majumdar defines varnashram dharma as: “rules of conduct enjoined on a man because he belongs to a particular caste and also to a particular stage of life, such as, ‘a Brahmin brahmacharin should carry a staff of palasha tree.’”9 What exactly did Bhaktivedanta Swami teach about varnasrama dharma, that up to this day many of his followers believe that its principles can turn the world—or at least ISKCON communities—into a better place?

THE LOWEST OF MANKIND

The earliest available reference to varnashram dharma occurs in a speech, “Solution of Present Crisis by Bhagwat Geeta,” delivered by Bhaktivedanta Swami in Madras in 1950, fifteen years before he founded his ISKCON movement in the West.10 Listing the causes of what he refers to as a crisis, he mentions among other things, “No training of human civilization. Varnashram Dharma.”11 Bhaktivedanta Swami’s idea of such training was first concretely outlined in a series of articles, “The Lowest of Mankind,” “Purity of Conduct,” and “Standard Morality.” Published in Delhi between 1956 and 1958, they appeared in Back to Godhead, his bimonthly magazine that he called “an instrument for training the mind and educating humanity to rise up to Divinity in the plane of the spirit soul.”12

In “The Lowest of Mankind” he declares that 99.9 percent of all humans are morally despicable (Sanskrit: naradhama), because they do not follow the regulations of varnashram dharma:

It is the duty of the guardians of children to revive the divine consciousness dormant in them. The ten processes of reformatory ceremonies as enjoined in the Manu-Smriti, which is the guide to religious principles, are meant for reviving God consciousness in the system of Varna Ashram. Nothing is strictly followed now in any part of the world and therefore 99.9 percent populations are Naradhama.13

Referring to the garbhadhan samskara, which he considers to be the most essential of the aforementioned ten ceremonies, he argues in “Purity of Conduct” that Hinduism lost its special significance since varnashram dharma is no longer followed:

The Garbhadhan Samskara is also a checking method for restricting bastard children. We do not wish to go into the details of the Garbhadhan Samskara or any other such reformatory processes but if need be we can definitely prove that since we have stopped observing these reformatory processes—the whole Hindu society has lost its special significance in the matter of social and religious dealings.14

And in “Standard Morality” he states that the varnashram system “is schemed for fulfilling the mission of human life by suitable division of departmental activities”15—a reference to varnas.

ISKCON SHALL SAVE THE WORLD

After 1965, when the International Society for Krishna Consciousness was founded, the need to reintroduce varnashram dharma worldwide became a central and recurring theme in Bhaktivedanta Swami’s books and talks:

The Krishna consciousness movement, however, is being propagated all over the world to reestablish the varnashram-dharma system and thus save human society from gliding down to hellish life.16

In order to rectify this world situation, all people should be trained in Krishna consciousness and act in accordance with the varnashram system.17

The Krishna consciousness movement is therefore very much eager to reintroduce the varnashram system into human society so that those who are bewildered or less intelligent will be able to take guidance from qualified Brahmins.18

Bhaktivedanta Swami apparently believed that all problems would be solved, the world situation would be rectified, and humanity would be saved from hellish life if only people could be made to accept guidance from his ISKCON Brahmins. Declaring that “without varnashram-dharma, materialist activities constitute animal life,”19 he repeatedly identifies varna sankara, mixed-caste people—or “unwanted population,” as he would also call them—as a key factor contributing to contemporary world problems.

Varna-sankara. There is no varnashram, therefore all the children, they are varna-sankara. And as soon as there is varna-sankara population, the world becomes hell. Therefore we are trying to check—“No illicit sex”—to stop this varna-sankara.20

There are so many talks about to keep the varnashram intact for peaceful condition of the society, and the modern problem, the overpopulation. . . . So there is no question of overpopulation. The question is varnas-sankara. Varna-sankara, that is the problem.21

But though he often declared that his movement was meant to reestablish varnashram dharma, Bhaktivedanta Swami occasionally admitted that it was no longer possible to do so: “Nobody can revive now the lost system of varnashram dharma to its original position for so many reasons.”22 “Nor is it now possible to reestablish the institutional function in the present context of social, political and economic revolution.”23

THE PROGRESSIVE MARCH OF THE CIVILIZATION OF THE ARYANS

The Sanskrit word aryah is not uncommon in the stanzas of the Bhagavata Purana. It is mainly used in the sense of “noble” or “respectable,” but never as a racial designation. Bhaktipada Swami, however, speaks extensively about “the Aryans”—at least twenty-five of his purports and over a hundred lectures and conversations contain lengthy elaborations on the topic. He places all those whom he calls “non-Aryan” in a category similar to his “unwanted population,” thus dividing humans into two groups: a large group of varna sankara and non-Aryans on one side, and a small group of Aryans, i.e., those who follow varnashram, on the other: “Those who traditionally follow these principles are called Aryans, or progressive human beings.”24 “The Vedic way of life,” he writes, “is the progressive march of the civilization of the Aryans.”25 “In the history of the human race, the Aryan family is considered to be the most elevated community in the world.”26

Most of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s statements define “Aryan” in social, religious, and cultural terms. However, in more than one fifth of his statements he clearly describes or defines them in racial terms:

The Aryan family is distributed all over the world and is known as Indo-Aryan.27

The Aryans are white. But here, this side, due to climatic influence, they are a little tan. Indians are tan but they are not black. But Aryans are all white. And the non-Aryans, they are called black. Yes.28

Dravidian culture. Dravida. They are non-Aryans. Just like these Africans, they are not Aryans . . . Shudras, black. So if a Brahmin becomes black, then he’s not accepted as Brahmin.29

On other occasions Bhaktivedanta Swami presents a mixture of both racial and sociocultural views regarding Aryans, such as when he appealed to his young western audiences:

So we all belong to the Aryan family. Historical reference is there, Indo-European family. So Aryan stock was on the central Asia. Some of them migrated to India. Some of them migrated to Europe. And from Europe you have come. So we belong to the Aryan family, but we have lost our knowledge. So we have become non-Aryan practically.30

You French people, you are also Aryan family, but the culture is lost now. So this Krishna consciousness movement is actually reviving the original Aryan culture. Bharata. We are all inhabitants of Bharatavarsha, but as we lost our culture, it became divided.31

So on the whole, the conclusion is that the Aryans spread in Europe also, and the Americans, they also spread from Europe. So the intelligent class of human being, they belong to the Aryans, Aryan family. Just like Hitler claimed that he belonged to the Aryan family. Of course, they belonged to the Aryan families.32

SCIENTIFIC ARYANS

Bhaktivedanta Swami used the expressions “Vedic civilization,” “Aryan civilization,” and “varnashram-dharma” as practically synonymous,33 and said that the purpose of his movement was “to make the people Aryan.”34 On numerous occasions he stated that his message was aimed at the intelligentsia:

This movement is meant for intelligent class of men, those who have reason and logic to understand things in a civilized way, and who are open-hearted to receive things as they are.35

It is not that everyone will be able to understand this philosophy. Still if some intelligent section of the human society understands it, there will be tremendous change in the atmosphere.36

It is not a sentimental movement. It is meant for the learned scholars and highly situated person.37

Intelligent class of men will take this sankirtana movement for his spiritual elevation of life. It is a fact, it is scientific, it is authorized.38

That varnashram dharma was something ancient and scientific turns out to be also the opinion of Kedarnath Datta Bhaktivinoda (father of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s guru), who, almost one hundred years earlier, had introduced the term vaijnanika varnashram. In Hindu Encounter with Modernity, Shukavak N. Dasa writes: “The system of varnas and ashrams that Bhaktivinoda refers to is not the traditional caste system of his time. In his opinion the existing caste system was only a remnant of the ancient and scientific vaijnanika-varnashram system.”39 Bhaktivinoda’s son Bimal Prasad, who later founded a Vaishnava organization in India and became known as Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati, or Siddhanta Saraswati, explained his movement, the Gaudiya Math, in the following manner:

This institution has undertaken the task of re-establishing the system of daiva-varnashram for reinstating such persons in the proper functioning of true Brahmins as have forgotten the principle of the dharma of jivas as servitors to Vishnavas [sic] and have been consequently running after the function of Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, etc.40

Countless statements in the books, lectures, and conversations of Bhaktivedanta Swami—himself a disciple of Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati—suggest that he shared the views of his direct predecessors. He too believed that in bygone ages a divine and scientific social system had existed in India, and like Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati, he too founded a movement whose express mission it was to reestablish what he often referred to as the “perfectional form of human civilization,” varnashram dharma.

VARNASHRAM IN THE BHAKTIVEDANTA PURPORTS

Unlike the earlier Bhagavata commentators, who hardly ever, and if at all, then only briefly, mention varnashram in their glosses, Bhaktivedanta Swami gives this topic great attention. Of the 113 purports in which he discusses it in his Srimad Bhagavatam, only 13 coincide with occasions where earlier commentators interpret certain words and referring to varnashram.41 Most of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s purports that discuss varnashram appear in a context where the topic had not been mentioned either in the text of the Bhagavata Purana itself or in any of the commentaries that he is known to have used.42

There are also cases in which Bhaktivedanta Swami backs his varnashram elaborations with references to earlier commentators that factually find no support in their original glosses. Here is just one example: “According to Viraraghava Acharya, such protection means organizing the citizens into the specific divisions of the four varnas and four ashrams. It is very difficult to rule citizens in a kingdom without organizing this varnashram-dharma.”43 Viraraghava, however, does not mention varnashram dharma in his commentary to this particular verse or in his commentaries to the directly preceding or following verses.44

In Bhaktivedanta Swami’s written commentaries, the Bhaktivedanta purports, to the Bhagavad Gita, the Bhagavata Purana, and the Chaitanya Charitamrita, there are all together three hundred explicit statements about varnashram dharma. These can be divided into five groups, namely statements about the status, purpose, restrictions, structure, and history of varnashram dharma.

The largest group, comprising 35 percent of all statements, concerns the status of varnashram dharma. Typical expressions in this category state that varnashram dharma is:

The perfectional form of human civilization.45

The beginning of human civilization.46

The natural system for civilized life.47

The beginning of actual human life.48

The beginning of the distinction between human life and animal life.49

The most scientific culture.50

A religion.51

Bhaktivedanta Swami’s statements about the purpose of varnashram dharma form the second-largest group with 32 percent. Statements typical for this category express that its purpose is:

To protect women from being misled into adultery.52

To train the followers to adopt the vow of celibacy.53

To train everyone so that the money is spent only for good causes.54

To turn a crude man into a pure devotee of the Lord.55

To prevent human society from being hellish.56

To make sure that the good population would prevail.57

To uplift all to the highest platform of spiritual realization.58

To satisfy the Supreme Lord.59

The third category, with 16 percent of all statements, deals with rules and restrictions imposed by varnashram dharma:

One has to retire from family life in middle age.60

Small boys after five years of age are sent to become brahmachari at the guru’s ashram.61

The varnashram-dharma scheme forbids or restricts association with women.62

A human being is expected to follow the rules and regulations of varna and ashram.63

The fourth category (14 percent) deals with the structure of, and people in, varnashram dharma:

The scientific system of varnashram-dharma divides the human life into four divisions of occupation and four orders of life.64

The irresponsible life of sense enjoyment was unknown to the children of the followers of the varnashram system.65

The fifth category, with only 3 percent of all statements, treats varnashram dharma from a historical perspective:

Indian civilization on the basis of the four varnas and ashrams deteriorated because of her dependency on foreigners, of those who did not follow the civilization of varnashram. Thus the varnashram system has now been degraded into the caste system.66

“WE ARE TRYING TO TRAIN SOME BRAHMINS TO GUIDE HUMAN SOCIETY”

In all of his books as well as throughout his lectures and conversations, Bhaktivedanta Swami shared his vision of establishing varnashram dharma worldwide. He was convinced that it was a practical sociopolitical structure that modern governments could implement, and that his movement would facilitate this by creating qualified Brahmins through some sort of suitable training or education:

At present this Krishna consciousness movement is training Brahmins. If the administrators take our advice and conduct the state in a Krishna conscious way, there will be an ideal society throughout the world.67

We are therefore creating Brahmins. We are not creating Shudras. Shudras are already there.68

They have no brain how to make the society peaceful and prosperous. They are Shudras. They have no intelligence. There is necessity of creating Brahmins and Vaishnava. This movement is meant for that purpose.69

We train them in austerities and penances and recognize them as Brahmins by awarding them sacred threads.70

There is a great need of Brahmins. Therefore, in the Krishna consciousness movement, we are trying to train some Brahmins to guide human society. Because at present there is a scarcity of Brahmins, the brain of human society is lost.71

While Bhaktivedanta Swami repeatedly spoke or wrote about training that would produce Brahmins, he delivered only very few concrete instructions about what exactly such training should consist of. When asked by a disciple how a Brahmin should be trained, he replied:

He must be truthful, he must control the senses, control the mind. . . . He must be tolerant. He should not be agitated in trifle matters. . . . He must by always clean. Three times he must take bath at least. All the clothing, all, everything is clean. This is brahminical training. And then he must know all what is what, knowledge, and practical application, and firm faith in Krishna. This is Brahmin.72

On another occasion he wrote to a disciple in India about his vision of a varnashram college. He thought that in such a college he could produce certified Brahmins who would then receive degrees from a local university. But in this letter too, there are no details about the training itself, only a list of desired end results:

As desired by you, I can immediately take up the task of opening a center there and to open a varna-asram college there affiliated by the university. In this college we shall train up pure Brahmins, (qualified Brahmins), Kshatriyas and Vaishyas. That is the injunction of Bhagavad-gita. . . . This system should be introduced. They must sit for proper examination after being trained. So, if we start a varna-asram college in terms of Bhagavat-gita instructions and approved by Shrimad-bhagavatam, why the university will not give degree to a qualified person as approved Brahmin.73

“KSHATRIYAS, THEY HAVE TO LEARN HOW TO KILL”

The above letter shows that Bhaktivedanta Swami not only wanted a Brahmin training but also had plans for kshatriya and vaishya training. Training Brahmins appears to have occupied the highest rank on his priority scale, but training kshatriyas was definitely important to him. However, the type of kshatriyas that he most often talked about were kings and rulers rather than common soldiers or administrators:

A Kshatriya should not be a coward, and he should not be nonviolent; to rule over the country he has to act violently.74

When asked by a disciple how the kshatriya training in the planned varnashram college was to be organized, he replied:

Just like material subject matter, Kshatriya, or the Brahmins, Kshatriya, as they are described in the Bhagavad Gita, what are the symptoms of Brahmin, what is the symptoms of Kshatriya. The Kshatriyas should be taught how to fight also. There will be military training. There will be training how to kill.75

Kshatriya students in the ISKCON varnashram college were to practice killing:

Just like Kshatriyas, they have to learn how to kill. So practically, they should go to the forest and kill some animal. And if he likes, he can eat also.76

There is no single instance where Bhaktivedanta Swami speaks about kshatriya training without mentioning killing. While he might not have considered it to be the most important aspect of that education, he does stress this aspect:

You can kill one boar. Some disturbing elements, you can kill. You can kill some tiger. Like that. Learn to kill. No nonviolence. Learn to kill. Here also, as soon as you’ll find, the Kshatriya, a thief, a rogue, unwanted element in the society, kill him. That’s all. Finish. Kill him. Bas. Finished.77

It is not that because the Kshatriyas were killing by bows and arrows formerly, you have to continue that. That is another foolishness. If you have got . . . If you can kill easily by guns, take that gun.78

All the royal princes were trained up how to kill.79

The killing is there, but the Brahmin is not going to kill personally. . . . Only the Kshatriyas. The Kshatriyas should be so trained up.80

A Kshatriya, he is expert in the military science, how to kill. So the killing art is there. You cannot make it null and void by advocating nonviolence. No. That is required. Violence is also a part of the society.81

“MONARCHY I HAVE SAID, BECAUSE THE POPULATION ARE ASSES”

Bhaktivedanta Swami often spoke about the ideal monarch: “So the kings were very severe to punish unwanted social elements,” and from his many outspoken statements against democracy it appears that he envisioned a return to monarchy:

Nowadays it is constitutional, democratic government. The king has no power. But this is not good for the people. The democracy is a farce. At least, I do not like it.83

The so-called democracy under party politics is nonsense. Monarchy . . . I have said. That day I was in remarking that “This democracy is the government of the asses,” because the population are asses and they vote another ass to be head of the government.84

On some occasions Bhaktivedanta Swami would denounce democracy as “demoncracy” or “demon-crazy.” Referring to Indira and Rajiv Gandhi, he asks “She and her son are the destiny of India? A woman and a debauch? They can do whatever they like. It’s a farce condition. That so-called democracy is nonsense demoncracy.”85 Two months later he asserts that democracy had not yet arrived in India:

This democracy is a demon-crazy. It has no value. It is simply waste of time and effort and no feeling, demon-crazy. I do not know who introduced this. In India still there is no demon-crazy. Indian king always. Everyone is taking part in politics. What is this nonsense? It is meant for the Kshatriyas. They can fight and defend.86

In a lecture in London in 1973, Bhaktivedanta Swami told his audience that his movement could help turn the British monarchy into some sort of Krishna conscious rule:

So again the monarchs, where there is monarchy, little, at least show of monarchy, just like here in England there is, actually if the monarch becomes Krishna conscious, actually becomes representative of Krishna, then the whole face of the kingdom will change. That is required. Our Krishna consciousness movement is for that purpose. We don’t very much like this so-called democracy.87

In numerous purports in his Shrimad Bhagavatam he describes the advantages a varnashram-based monarchy would have over democratic governments:

Monarchy is better than democracy because if the monarchy is very strong the regulative principles within the kingdom are upheld very nicely.88

In such dealings, a responsible monarchy is better than a so-called democratic government in which no one is responsible to mitigate the grievances of the citizens, who are unable to personally meet the supreme executive head. In a responsible monarchy the citizens had no grievances against the government, and even if they did, they could approach the king directly for immediate satisfaction.89

When monarchy ruled throughout the world, the monarch was actually directed by a board of Brahmins and saintly persons.90

The modern democratic system cannot be exalted in this way because the leaders elected strive only for power and have no sense of responsibility. In a monarchy, a king with a prestigious position follows the great deeds of his forefathers.91

Gradually the democratic government is becoming unfit for the needs of the people, and therefore some parties are trying to elect a dictator. A dictatorship is the same as a monarchy, but without a trained leader. Actually people will be happy when a trained leader, whether a monarch or a dictator, takes control of the government and rules the people according to the standard regulations of the authorized scriptures.92

Statements like the last one, in which Bhaktivedanta Swami declares that he favors even dictatorship above democracy, are by no means rare:

So monarchy or dictatorship is welcome. Now the Communists, they want dictatorship. That is welcome, provided that particular dictator is trained like Maharaja Yudhisthira.93

I like this position, dictatorship. Personally I like this.94

Bhaktivedanta Swami's appreciation for dictatorship is further underlined by his generally approving remarks about Hitler. While he often mentions Hitler to give an example of materialistic scheming, he nevertheless calls him a hero and a gentleman:

Why should our temples support or denounce Hitler. If somebody says something in this connection it must simply be some sentiment. We have nothing to do with politics.95

So these English people, they were very expert in making propaganda. They killed Hitler by propaganda. I don’t think Hitler was so bad man.96

Hitler knew it [the atom bomb] . . . everything, but he did not like to do it. . . . He was gentleman. But these people are not gentlemen. He knew it perfectly well. He said that “I can smash the whole world, but I do not use that weapon.” The Germans already discovered. But out of humanity they did not use it.97

Sometimes he becomes a great hero—just like Hiranyakashipu and Kamsa or, in the modern age, Napoleon or Hitler. The activities of such men are certainly very great, but as soon as their bodies are finished, everything else is finished.98

Therefore Hitler killed these Jews. There were financing against Germany. Otherwise he had no enmity with the Jews. . . . And they were supplying. They want interest money—“Never mind against our country.” Therefore Hitler decided, “Kill all the Jews.”99

VAISHYAS

Bhaktivedanta Swami did not have much to say about vaishyas, or the mercantile class, as he would often call them. “Vaishyas should be trained how to give protection to the cows, how to till the field and grow food,” was his standard comment regarding their place in a varnashram society.100 When asked how vaishyas should be trained in his varnashram college and whether they should learn how to do business, he replied:

We are not going to open mills and factories and . . . No. We are not going to do that. That is Shudra business. The real business is that you produce enough food grains, as much as possible, and you eat and distribute. That’s all. This is business. He does not require any so high technical education. Anyone can till the ground and grow food.101

Two years later, in a conversation with Indian politicians, he restates his opinion that vaishyas do not require education:

So therefore I say that there must be educational institution for training Brahmin, Kshatriya especially. And Vaishyas, they do not require any academical area. . . . They can learn simply by associating with another Vaishya.102

When talking about vaishyas, Bhaktivedanta Swami often brought up the following rule, apparently designed by him: “Kshatriyas and Vaishyas are therefore especially advised to give in charity at least fifty percent of their accumulated wealth.”103 This 50-percent charity tax might have been an early attempt to inspire followers not living in the temple to financially support his movement:104

The householder should earn money by business or by profession and spend at least fifty percent of his income to spread Krishna consciousness; twenty-five percent he can spend for his family, and twenty-five percent he should save to meet emergencies.105

Grihasthas, those who are in householder life outside, are expected to contribute fifty-percent of their income for our society, keep twenty-five percent for family, and keep twenty-five percent for personal emergencies.106

The system did not become the norm in ISKCON during Bhaktivedanta Swami’s time, probably because most members preferred to remain in the temples, even after getting married, rather than practice “householder life outside.” And after his death, when many moved out of the American temples, the 50-percent rule was practically never followed.

SHUDRAS

Regarding the question whether shudras should be counted among the Aryans, Bhaktivedanta Swami made conflicting statements: “Shudras means non-Aryan. And Aryans, they are divided into three higher castes.”107 “Aryans are divided into four castes.”108 His remarks regarding training for shudras are also contradictory. When asked what kind of training they should receive in his varnashram college, he replied:

“Do this.” That’s all. Yes. That is also training, to become obedient. Because people are not obedient. . . . So obedience also require training. If you have no intelligence, if you cannot do anything independently, just be obedient to the other, higher three classes. That is Shudra. . . . Little arts and crafts can be trained up to the Shudras.109

On a different occasion, however, he asserts that shudras do not require any training at all:

Shudras does not require any training. Shudra means no training. Ordinary worker class. Otherwise other three, especially two, namely the Brahmins and Kshatriyas, they require very magnificent training.110

On the whole, Bhaktivedanta Swami’s attitude toward shudras appears to be rather negative. While he depicts the other three varnas in positive or at least neutral terms, his description of shudras sounds harsh, spiteful, and condescending. Most of his remarks begin with the “Shudra(s) means,” typically followed by:

ordinary people; the laborer class; once-born; the lowest class of men; non-Aryan; worker; the black man; he must find out a master; one who has no education; almost animal; without any culture; fourth-class men; ordinary worker; dog; no intelligence, little better than animals; they do not know what is the aim of life, just like animal; just like a dog; he becomes disturbed; one who is dependent on others; they are ignorant rascals; unclean; equal to the animal; no training; fools, rascals.111

It is hard not to perceive racist undertones in many of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s statements about shudras. According to his understanding, people of black or dark skin color, as well as native Americans, are shudras, third-class, degraded, and less intelligent:

Shudras have no brain. In America also, the whole America once belonged to the Red Indians. Why they could not improve? The land was there. Why these foreigners, the Europeans, came and improved? So Shudras cannot do this. They cannot make any correction.112

A first-class Rolls Royce car, and who is sitting there? A third-class negro. This is going on. You’ll find these things in Europe and America. This is going on. A first-class car and a third-class negro. That’s all.113

But his bodily feature, he was a black man. The black man means Shudra. The Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya, they were not black. But the Shudras were black.114

In the last statement Bhaktivedanta Swami is commenting on the passage “nrpa-linga-dharam shudram,” from Bhagavata Purana 1.16.4. The verse mentions the evil spirit Kali, describing him as “a shudra having royal insignia.” Neither the verse nor any of the earlier commentators mention that this personality should have been black. It looks like Bhaktivedanta Swami considered having black skin color and being evil to be closely related features. He certainly considered black people to be ugly: “Such action of the cupid is going on even on the negroes and beastly societies who are all ugly looking in the estimation of the civilized nations.”115

In February 1977, less than a year before his death, Bhaktivedanta Swami expressed regret about the fact that America had abolished slavery. In a room conversation, which later received the title “Varnashram System Must Be Introduced,” he referred to African Americans as follows:

Shudra is to be controlled only. They are never given to be freedom [sic!]. Just like in America. The blacks were slaves. They were under control. And since you have given them equal rights they are disturbing, most disturbing, always creating a fearful situation, uncultured and drunkards. What training they have got? They have got equal right? That is best, to keep them under control as slaves but give them sufficient food, sufficient cloth, not more than that. Then they will be satisfied.116

It was probably not at all unusual for Bhaktivedanta Swami to reason in these ways, for, as he had once told his disciples: “So the Kiratas, they were always slaves of the Aryans. The Aryan people used to keep slaves, but they were treating slaves very nicely.”117 And that the Kiratas were Africans he had explained many times: “Kirata means the black, the Africans.”118

One wonders how Bhaktivedanta Swami, who repeatedly identified “the intelligent class of men” as the main target of his preaching, could present to them his program of turning back the clock by several centuries of human social thought and still expect it to be favorably received. Although he had often stressed that his message was meant for “the intelligent class of men,” he had just as often declared that the entire world population were shudras: “At the present moment, they are Shudras or less than Shudras. They are not human beings. The whole population of the world.”119

Bhaktivedanta also thought that he and his movement could take over some government and rule some part of the word: “However, in Kali-yuga, democratic government can be captured by Krishna conscious people. If this can be done, the general populace can be made very happy.”120 One other occasions he urged his followers not to take his message lightly. He promised doom and gloom to those who failed to accept and follow his instructions: “Don’t think that Krishna consciousness is a joke, is a jugglery. It is the only remedy if you want to save yourself. Otherwise, you are doomed. Don’t take it, I mean to say, as a joke. It is a fact.”121 He thought that his varnashram college could save the word, and that even the shudras would come to like it:

Unless they take to Krishna consciousness, they’ll not be saved. The varnashram college has to be established immediately. Everywhere, wherever we have got our center, a varnashram college should be established to train four divisions: one class, Brahmin; one class, Kshatriya; one class, Vaishya; and one class, Shudra. But everyone will be elevated to the spiritual platform by the spiritual activities which we have prescribed. There is no inconvenience, even for the Shudras.122

ASHRAM

In the classical varnashram system there are four ashrams, stages of life: brahmacharin, grihastha, vanaprastha, and sannyasa (celibate student, married householder, celibate recluse, and celibate mendicant). In Bhaktivedanta Swami’s vision of establishing varnashram dharma worldwide, there was also a plan for what might be called “ashram training.” However, throughout his books and lectures he focuses only on training for the first ashram: celibate student. While he does speak about grihasthas, he does not mention anywhere that they would require some sort of training, and the vanaprastha topic is virtually absent. The sannyasa ashram could in a way be seen as an extension of the celibate student status, but if one considers how freely Bhaktivedanta Swami turned his young male disciples without much preparation into fully ordained sannyasins, it seems that even sannyasa training was not much of a priority for him.

In contrast, there is an abundance of references to training young boys to become exemplary—lifelong, if possible—celibates. One thing that most of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s statements regarding brahmachari training have in common is the emphasis on the need to start it as early as possible. He typically mentions five years of age as being the “Vedic standard,” and consequently urges his disciples to send their children to his ISKCON gurukula schools at this age at the latest:

Children at the age of five are sent to the guru-kula, or the place of the spiritual master, and the master trains the young boys in the strict discipline of becoming brahmacharis.123

In the system of varnashram-dharma, which is the beginning of actual human life, small boys after five years of age are sent to become brahmachari at the guru’s ashram.124

The Krishna consciousness movement encourages marriage not for the satisfaction of the genitals but for the begetting of Krishna conscious children. As soon as the children are a little grown up, they are sent to our Gurukula school in Dallas, Texas, where they are trained to become fully Krishna conscious devotees. Many such Krishna conscious children are required, and one who is capable of bringing forth Krishna conscious offspring is allowed to utilize his genitals.125

Encouraging one of his disciples to send her son to the school in Dallas, he wrote:

Recently I have visited our Gurukula school in Dallas, and I was quite satisfied how the boys and girls are being trained up to be ideal Vaishnavas. This training from an early age is important, and I also was fortunate to receive such training when I was a child.126

The above statement by Bhaktivedanta Swami, however, should not be misunderstood to mean that he too was sent away from home to a distant gurukula at the age of five. He attended a regular, secular day school in Calcutta. Still, he was convinced that it was beneficial for the children of his disciples to be separated early from their parents.

That is a good proposal, that parents should not accompany their children. Actually that is the gurukula system. The children should take complete protection of the Spiritual master, and serve him and learn from nicely. Just see how nicely your brahmacharis are working. They will go out in early morning and beg all day on the order of the guru. At night they will come home with a little rice and sleep without cover on the floor. And they think this work is very pleasant. If they are not spoiled by an artificial standard of sense gratification at an early age, children will turn out very nicely as sober citizens, because they have learned the real meaning of life. If they are trained to accept that austerity is very enjoyable then they will not be spoiled. So you organize everything in such a way that way can deliver these souls back to Krishna—this is our real work.127

Bhaktivedanta Swami never missed an opportunity to canvass for the Dallas gurukula. He taught that “real affection” for one’s child means to send the child away from the parents to his Bhaktivedanta gurukula, if possible already at the age of four:

Rather, all of our children should go to Dallas when they are four and begin their training program there. In Dallas, they have full facility approved by me, I have personally seen that they are doing very nicely there. . . . But our affection is not simply sentimental, we offer our children the highest opportunity to become trained up in Krishna consciousness very early so as to assure their success in this life to go back to Godhead for sure. That is real affection, to make sure my child gets back to Godhead.128

Now we have gone to Dallas where I am visiting in the Gurukula school. It is very first class school and church and I think it is better than Los Angeles Temple. We have got very many children here and I am teaching the way how to give them instruction in Krishna consciousness. It is the first class place to send your son when he is old enough to come here.129

In this letter Bhaktivedanta Swami writes that he is personally teaching “the way how to instruct the children.” He was apparently concerned to win the trust of the parents, and to assure them that things were conducted in responsible ways and under his supervision. Typical instructions regarding child education that he often gave to parents, teachers, and leaders are:

Therefore our young men must be trained at the earliest age to not be attached to so many things like the home, family, friendship, society, and nation. To train the innocent boy to be a sense gratifier at the early age when the child is actually happy in any circumstance is the greatest violence.130

You should give all freedom to your child for five years, and then, next ten years, you should be very strict, very strict, so that the child may be very much afraid.131

Unfortunately, this training is lacking all over the world. It is necessary for the leaders of the Krishna consciousness movement to start educational institutions in different parts of the world to train children, starting at the age of five years.132

Every mother, like Suniti, must take care of her son and train him to become a brahmachari from the age of five years and to undergo austerities and penances for spiritual realization.133

As education begins at the age of five years, similarly, Krishna consciousness, or Bhagavata-dharma, should be taught to the children as soon as the child is five years old.134

But in spite of all these detailed instructions, it appears that something went wrong in the Dallas gurukula and sometime in 1976 it was threatened with closure. Bhaktivedanta Swami’s effort to save the project by appealing to the parents not to withdraw their children from the school shows how important ashram training was to him. In a circular dated 4 March 1976, he wrote to the parents:

My Dear parent,

Please accept my blessings. There has been a serious mistake. I do not wish that Gurukula should be closed down in Dallas. So you kindly arrange to send your child back to Gurukula.135

Bhaktivedanta Swami was in fact quite adamant when it came to the question of child education. When one of his disciples, herself a gurukula teacher, reminded him that he had once said that “some parents can keep their children with them and teach themselves,”136 he rebuked her:

You follow that, brahmachari gurukula, that I’ve already explained. That should be done. Don’t bring any new thing, imported ideas. That will not be helpful. It will be encumbrance. “My experiment with truth”—Gandhi’s movement. Truth is truth. “Experiment” means you do not know what is truth. It is a way of life, everything is stated there, try to train them. Simple thing.137

When he says: “You follow that, brahmachari gurukula,” Bhaktivedanta Swami refers to a passage from Bhagavat Purana 7.32.1 (“brahmachari gurukule”), wherein it is stated that a celibate student should live at the guru’s ashram. He insisted that his instructions, based on his understanding of certain scriptural passages, had to be followed with absolute obedience. He thus disliked the idea that children should stay with or be taught by their parents. In fact, he regarded separation from the parents to be a vital aspect of the child’s spiritual education. That boys should be separated from their parents at the age of five was rule based on Bhaktivedanta Swami’s interpretation of Bhagavata Purana 7.6.1: “kaumara acharet prajno,” “the wise should begin worship in childhood,” a passage he quoted over a hundred times in his books and lectures. The personality who speaks this passage is the child saint Prahlada, who, along with the child saint Dhruva, became the emblem of childhood bhakti success in Bhaktivedanta Swami’s preaching.

Bhaktivedanta Swami was so convinced of the superiority of his gurukula schooling system that he instructed one of his leading disciples to organize the schools in such a way that even non-ISKCON members would want to send there children there:

They should be given only what they will eat, so that nothing is left over, and while bathing they can wash their own cloth. Your country, America, will become so much degraded that they will appreciate if we are revolutionary clean. Our revolutionary medicine will be experimented on these children, and it will be seen in America to be the cure. So make your program in this way, and encourage nondevotees or outsiders to enroll their children with us for some minimum fee, and you will do the greatest service to your country and its citizens by introducing this.138

Now I am concerned that the Gurukula experiment should come out nicely. These children are the future hope of our Society, so it is a very important matter how we are training them in Krishna consciousness from the very childhood.139

In the above-quoted passages Bhaktivedanta Swami refers to his instructions regarding child education as “revolutionary medicine.” He speaks about “the Gurukula experiment,” and orders his disciples test his “medicine” on their children. Many years later ISKCON leaders were forced to acknowledge that the outcome of his “experiment” was radically different than expected.

Most of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s statements about child education leave no doubt that he was mainly thinking about how to train boys. As far as girls were concerned, he appears rather reserved:

Girls should be completely separated from the very beginning. They are very dangerous . . . No girls. . . . They should be taught how to sweep, how to stitch . . . clean, cook, to be faithful to the husband. They should be taught how to become obedient to the husband. Little education, they can. . . . They should be stopped, this practice of prostitution. This is a very bad system in Europe and America. The boys and girls, they are educated—coeducation. From the very beginning of their life they become prostitutes. And they encourage.140

When asked whether his varnashram college would be open for women also, he replied:

For men. Women should automatically learn how to cook, how to cleanse home. . . . Varnashram college especially meant for the Brahmin, Kshatriya and Vaishya. Those who are not fit for education, they are Shudras. That’s all. Or those who are reluctant to take education—Shudra means. That’s all. They should assist the higher class.141

WOMEN’S ROLE IN THE ISKCON VARNASHRAM MODEL

While Bhaktivedanta Swami was known to have been kind and accommodating in dealings with his women disciples, most of what he wrote about women in his books, lectures, and conversations appears rather negative. (For a detailed analysis of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s statements about women, see E. Lorenz, “The Guru, Mayavadins, and Women: Tracing the Origins of Selected Polemical Statements in the Work of A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami,” in this volume.) Just like with shudras, he does not have much good to say about women:

Women are generally not very intelligent.142

Women in general should not be trusted.143

Generally when a woman is attacked by a man—whether her husband or some other man—she enjoys the attack, being too lusty.144

It may be clearly said that the understanding of a woman is always inferior to the understanding of a man.145

One gets the impression he saw women primarily as wombs, used by the Aryans for the purpose of perpetuating a race of saintly heroes. “The whole purpose of this system is to create good population,”146 writes Bhaktivedanta Swami about varnashram dharma. “According to Vedic rites, the breeding of child is very nicely enunciated. That is called garbhadhan-samskara.”147 When Bhaktivedanta Swami speaks about women in the context of varnashram, he inevitably brings up the topics of bad population, adulteration, prostitution, varna sankara, women’s lesser intelligence, and the lifelong control of women by men.

Women cannot properly utilize freedom, and it is better for them to remain dependent. A woman cannot be happy if she is independent. That is a fact. In Western countries we have seen many women very unhappy simply for the sake of independence. That independence is not recommended by the Vedic civilization or by the varnashram-dharma.148

And Shudras, they are not taken into account. In the similarly, woman class, they are taken as Shudra, Shudra. . . . Woman class are taken less intelligent, they should be given protection, but they cannot be elevated.149

If women become prostitute, then the population is varna-sankara. And varna-sankara means unwanted children. They become practically nuisance in the society. . . . If varna-sankara population is increased, then the whole society becomes a hell. That’s a fact.150

What Bhaktivedanta Swami might have had in mind when he used the word “prostitute” can perhaps be guessed from his statements about the former Indian prime minster, Indira Gandhi:

Prabhupada: And Indira was doing that. Indira and company. . . . She is a prostitute; her son is a gunda. . . .

Tamala Krishna: She seems to have been one of the worst leaders so far.

Prabhupada: She is not leader, she is a prostitute. Woman given freedom means prostitute. Free woman means prostitute. What is this prostitute? She has no fixed-up husband. And free woman means this, daily, new friend.151

His greatest concern seems to be how to avoid varna sankara. Again and again this topic comes up when women are mentioned in the varnashram context:

When women become polluted, no fixed-up husband—that is pollution for woman, no chaste, no chastity—then this varna-sankara will come out. And when the world is overpopulated by varna-sankara, it will become a burden. Therefore it so became, atheist, varna-sankara, demons.152

If the woman becomes widow, then there will be varna-sankara population. Varna-sankara population means a population who cannot say who is his father. That is varna-sankara. Or which caste does he belong, what is his father, what is his family. No, nothing, no information. That is called varna-sankara.153

The last statement speaks for itself; a widowed woman is “by default” a prostitute. The less intelligent women are so prone to degradation that unless they are kept under the tight control of men, they are sure to become pregnant, and the result will be the dreaded varna sankara. Bhaktivedanta Swami therefore advises his disciples: “And being the weaker sex, women require to have a husband who is strong in Krishna consciousness so that they may take advantage and make progress by sticking tightly to his feet.”154

IMPLEMENTATION OF VARNASHRAM IN ISKCON

Bhaktivedanta Swami’s declaration that his writings were “meant for bringing about a revolution in the impious life of a misdirected civilization” appears in the preface to each published volume of his commentaries to the Bhagavata Purana.155 What sort of impression did his teachings about varnashram dharma leave in the minds of his disciples? Did they try to implement his varnashram instructions?

One ISKCON project in which some—perhaps the most far-reaching—of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s varnashram instructions came to be implemented was the Bhaktivedanta gurukula in Dallas. Jeff Hickey, former Jagadish Das, who had been appointed by Bhaktivedanta Swami as his “education minister” and was in charge of the entire ISKCON gurukula education, recently appeared on a TV show and commented on his involvement:

Jeff Hickey: I really believed that I was doing the best for my children. I thought that this was a divine system that would give them the best training for the future that they were going to meet.

John Quinones: You were looking out for your child’s best interest?

Jeff Hickey: I thought so.

John Quinones (VO): Jeff was 19 when he became a Hare Krishna devotee in 1968. He followed the teachings of this man, the guru who brought the movement to America. Swami Prabhupada, who died in 1977, is still the most revered man in the religion. The swami put Jeff in charge of the Dallas school, then appointed him to be his minister of education, even though Jeff admits he had absolutely no experience in the field. It was Jeff who kept the children away from their parents. Now, he regrets following the Swami’s orders.

Jeff Hickey: It is my opinion that he didn’t know what he was doing, and that he—he made a huge mistake by separating the children from their parents and—and really, like, crushing their emotional lives.156

Another, rather brief project was the attempt to run a varnashram college in New Vrindavan, West Virginia. Many of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s statements quoted in the present paper are taken from a morning walk conversation recorded in Vrindavan, India, in March 1974. It was after this morning walk that the idea of a varnashram college began to circulate, and sometime in April the first varnashram college was started. Hiranyagarbha Das, who had been appointed “headmaster” of the varnashram college, remembers his involvement in the project:

The experiment was short-lived. We lasted only 8 months or so. In December, I took the boys on a book distribution trip to Buffalo and Toronto, and then returned to Dallas, where I unilaterally put an end to the experiment. I can’t remember any real repercussions from that.157

When asked whether ISKCON members in those days showed any awareness of how violent some of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s instructions regarding Kshatriya training actually were, Das replies:

Not really. Even so, in New Vrindavan, while I was there, Kirtanananda brought in some ex-military devotees who spent a bit of time setting up a Kshatriya group in the community. The mood was pretty militaristic at the time. I read somewhere that K. deliberately exploited (and maybe even fabricated) an incident in which some rough types attacked the temple in order to build up this kind of fortress mentality. It infected the Varnashram College to some degree also. We had some military type disciple—marching to the Hare Krishna mantra, etc. Eventually, we see where all this led to in New Vrindavan.158

Regarding how a person’s varna was to be determined in varnashram college, Bhaktivedanta Swami had once said that this “will be tested by the teachers, what for he is fit. He will be test [sic] by the guru.”159 When asked whether any such testing was actually practiced in the varnashram college, Das explained:

As I said above, this was not really touched upon, because Prabhupada confused the issue by assuming that everyone who came to the temple was automatically a Vaishnava and beyond being even a Brahmin, and therefore able to do any kind of work “to teach and set example.” So, stupidly, everyone in the movement was simply dumped onto the sankirtana [canvassing] party to collect [money], without consideration for his or her individual character or propensities.160

In 1981, four years after Bhaktivedanta Swami’s death, two of his leading disciples, Robert Campagnola and Jay A. Matsya,161 coauthored Varnashram Manifesto for Social Sanity,162 a volume dedicated to Bhaktivedanta Swami, “the real father of the modern varnashram system.”163 The book was controversial. Some felt that it was overly fanatical and could lead to public relations problems for ISKCON—which it actually later did: the anticult movement and the Orthodox Church in Russia used passages from the book to prove that ISKCON was driving a dangerous political agenda and could be potentially harmful to society. A detailed study of the 215-page text, however, reveals that Matsya and Campagnola faithfully repeat Bhaktivedanta Swami’s teachings on varnashram dharma:164

In the present period of the earth’s history, the books of His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada are the absolute foundation upon which all individual and collective spiritual progress depends. Since the departure of His Divine Grace from this mortal world, his disciples have inherited the task of expanding the original Vedic knowledge for the benefit of materially attached humanity. No one can become full spiritually enlightened without the help of transcendental literature written by Shrila Prabhupada and his authorized disciples. Nor can anyone completely change human society for the permanent good without these books’ clear and powerful guidance.165

While William H. Deadwyler finds the Varnashram Manifesto to be “spectacularly unpersuasive,”166 it cannot be denied that Matsya and Campagnola’s views on child education completely agree with Bhaktivedanta Swami’s teachings:

From the early years of life, children should hear correct knowledge of the material and spiritual realities. They should learn to understand the difference between matter and spirit, and the predominance of spirituality over material ignorance. By chanting songs and mantras that glorify the Supreme Lord, they should put this knowledge into action and thus purify their consciousness. The self-centeredness and selfishness of childhood are a form of material contamination. Young children desire to be the controllers and enjoyers of their little world. Expert at manipulating their parents by crying and smiling, young children have complete opportunity to maintain the illusions that they are their material bodies and the whole world is subject to their beck and call. Such illusions must be dealt with as soon as the child’s cognitive powers develop. Behind the carefreeness and glee of childhood lurk dormant, strong material desires. Although young children are sometimes believed to be “innocent and pure,” there is no question of actual innocence or purity; there is only the question of time. Because young children’s bodies and sensual powers have not fully developed and matured, they do not yet have the ability to manifest their inherent material desires. But as soon as the biological light turns green, they begin to contemplate and execute their formerly dormant desires for sense gratification. Hence, in a varnashram society, when children reach the age of five, the Brahmins will begin to train them in the correct understanding of the purpose of human life. When from an early age children develop the crucial qualities needed to conquer over material desires that will later arise to disturb them, then society is spared from many social problems.167

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Bhaktivedanta Swami left no doubt in his writings that he wanted his movement to save the world by establishing varnashram dharma:

So we shall have a unique position all over the world provided we stick to the principles, namely unflinching faith in Spiritual Master and Krishna, chanting not less than 16 rounds regularly and following the regulative principles. Then our men will conquer all over the world.168

Given the hurts that ISKCON members have inflicted on one another in their endeavor to please their guru, it can hardly be seen as unfortunate that they ultimately failed to fulfill his dream of taking over the world. While Bhaktivedanta Swami did not leave concrete instructions on how to go from modern democracy to a varnashram-based monarchy, he hoped to convince the intellectual elite of the world with the help of a perfect educational model: his Bhaktivedanta gurukula. There he wanted to create perfect Vaishnava Brahmins, children of exemplary character, who, by dint of their spiritual purity, would be able “to ignite the sacrificial fire without matches, solely by chanting mantras.”169 Other papers in this volume have discussed the results of this gurukula educational experiment.

ISKCON is presently trying to come to grips with its past. There have been official statements acknowledging that abuse of children in the Bhaktivedanta gurukula was a fact, and that it is regretted. There have also been official GBC resolutions regarding the treatment of women. Here too, regret for past abuses has been expressed. Efforts are under way to create an ISKCON that is not friendly and accommodating toward sannyasins and celibate males only, but also to families, women, and children. However, in the society’s attempts to examine its past and to understand what went wrong and why, very little progress has been made in identifying the underlying causes. The consensus seems to be that the movement was too liberal in its enrollment procedures, and that for this reason “bad elements” managed to enter, even into the leading echelons. Another popular explanation is that the members failed to correctly understand and execute Bhaktivedanta Swami’s perfect instructions.

It is a theological dogma in the movement that Bhaktivedanta Swami is a pure representative of God, incapable of error, all-knowing, and absolutely good. Since Bhaktivedanta Swami taught that criticism of a pure devotee was the most serious and devastating impediment to spiritual progress,170 a question that ISKCON leaders presently do not dare to consider is to what degree his teachings contribute to past abuses. It is no secret that many ISKCON leaders knew about the abuse, for example, of women and children, but often did not perceive this as in any way contrary to Bhaktivedanta Swami’s teachings. It used to be standard to first of all examine whether a current practice was justifiable in the light of Bhaktivedanta Swami’s teachings; it was—and still is—always secondary to ask whether any such practice agrees with commonly accepted ethical or social norms.

END NOTES

1. http://www.prabhupada.com/publishing.html

2. http://krishna.org/ctfote/varnash.html

3. http://www.floridavediccollege.edu/masters.htm

4. SS: Vedic Social Science, SS201: Varnashram Dharma—Vaisnava Social Responsibility. 3 Credits. Prescribed social duties in light of Vaisnavism; SS202: Applied Varnashram Dharma Studies—6 Credits. Prerequisite SS201. A study of Varnashrama by studying the lives of famous Vedic personalities and how they integrated Varnashrama Dharma into the fabric of their lives. http://bhaktivednta-college.org/index.htm

5. The General Headquarters homepage: http://www.ghq.org/index.html

6. “It is ISKCON’s responsibility to revive Vedic culture. Feminism—the ideology of female occupational equal rights is diametrically opposed to the principles of prescribed duties. There a feminist Vaisnava is an oxymoron.” “Vaisnavism and Social Responsibility,” http://ghq.org/download/.

7. Ravindra Svarupa Dasa (William H. Deadwyler), “ISKCON and Varnashrama-Dharma: A Mission Unfulfilled,” ISKCON Communications Journal 7 (1) (June 1999): 41.

8. “You will recall that Prabhupada originally thought that ISKCON would perform the brahminical function for the rest of society—‘I have come to give you a brain.’ Prabhupada based this effort on books. By books he could transmit the Vedic heritage, and through books he could instruct and train large numbers of followers, who, by studying his writings systematically and practicing their teachings, could advance to the mode of goodness and beyond.” Ibid.

9. A. K. Majumdar, Concise History of Ancient India: Vol. 3, Hinduism: Society, Religion & Philosophy (Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1983), 1.

10. Lecture at Sri Goudiya Math, Royapettah, Madras, 10 September 1950, The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM: Pre-1965 Writings (Sandy Ridge, NC: Bhaktivedanta Archives, 1995), record 13681-13749.

11. Ibid., record 13722.

12. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Back to Godhead 1944-1960 The Pioneer Years: A Collection of Back to Godhead Magazines Published between 1944 and 1960 (Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1994), 75, BTG vol. 3 part 1, 1 March 1956.

13. Ibid., record 13722.

14. Ibid., 114, BTG vol. 3 part 7, 5 June 1956.

15. Ibid., 155, BTG vol. 3 part 14, 20 November 1958.

16. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Fifth Canto (Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1987), 5.19.19 purport, p. 713.

17. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Fourth Canto (Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1987), 4.14.20 purport, p. 671.

18. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Tenth Canto (Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1987), 10.8.6 purport, p. 336

19. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Seventh Canto (Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1987), 7.15.36 purport, p. 859.

20. Room conversation with Sanskrit professor, other guests, and disciples, 12 February 1975, Mexico, The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM (Sandy Ridge, NC: Bhaktivedanta Archives 1995) record 444187.

21. Ibid., Lecture at World Health Organization, Geneva, 6 June 1974, record 379897.

22. Essays: Perfection at Home—A Novel Contribution to the Fallen Humanity, The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM: Pre-1965 Writings, record 14311.

23. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Second Canto (Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1987) 2.4.18 purport, p. 216.

24. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Third Canto (Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1987), 3.12.35 purport, 1:524.

25. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: First Canto (Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1987), 1.18.45 purport, p. 1049.

26. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Fourth Canto (Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1987), 4.20.26 purport, 2:39.

27. Ibid.

28. Lecture: Srimad-Bhagavatam 6.1.6 Bombay, 6 November 1970, The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, 1995, record 356922.

29. Ibid., Room Conversation, 2 August 1976, Paris, record 514967.

30. Ibid., Lecture: Bhagavad-gita 10.4-5, New York, 4 January 1967, record 33580.

31. Ibid., Lecture: Srimad-Bhagavatam 2.1.5, Paris, 13 June 1974, record 349711.

32. Ibid., Lecture: Bhagavad-gita 9.3, Melbourne, 21 April 1976, record 334397.

33. Ibid., Lecture at World Health Organization, Geneva, 6 June 1974, record 379907: “So really, Indian Civilization or Aryan civilization, Vedic civilization, means varnashrama-dharma.”

34. Ibid., Press Conference, Mauritius, 2 October 1975, record 469812.

35. Ibid., Letter to: Kirtanananda, Montreal, 30 June 1968, record 582228.

36. Ibid., Letter to: Bali-mardana, Nairobi, 9 October 1971, record 594201.

37. Ibid., Lecture: Sri Chaitanya-Charitamrita, Madhya-lila 20.100-108, Bombay, 9 November 1975, record 368302.

38. Ibid., Lecture: Bhagavad-gita 2.18, Hyderabad, 23 November 1972, record 323377.

39. Shukavak N. Dasa, Hindu Encounter with Modernity: Kedarnath Datta Bhaktivinoda Vaishnava Theologian (Los Angeles: Sri, 1999), 212.

40. Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati, Shri Chaitanya’s Teachings, part 1 (Madras: Sree Gaudiya Math, 1975), 312.

41. Viraraghava Acharya, for example, commenting on the word lokanam, explains that it refers to the followers of Varnashrama dharma: “lokanam varnashrama-vatam.” Shridhara Svami, commenting on the word setavah, explains that it refers to the boundaries of varnashram dharma: “setavo varnashrama-dharma-maryadah.” Srimad Bhagavata Sridhari Tika (1988: reprint, Bombay: Nirnaya Sagar Press, 1950), 7.8.48, p. 689: “setavo varnashram-dharma-maryadah.”

42. In only 29 out of 113 purports that mention varnashram, Bhaktivedanta Swami comments on Bhagavat Purana passages that contain obvious keywords like varna, ashram, or dharma.

43. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Fourth Canto, 4.29.81 purport, 2:791.

44. Krsnasankara Sastri, ed., Srimad-bhagavata-mahapuranam caturtha skandhah (Sola: Sri Bhagavata-Vidyapitah, 1966), 4.29.81 srimad viraraghavavyakhya, p. 762. What Viraraghava actually wrote is, “tatah prachinabarhih praja-shristau tad-rakshane cha sva-putran anujnapya svayam taps chartum kapilashramam agat.” “Having instructed his sons about increasing and protecting the subjects, Prachinabarhi went to Kapilashram to perform austerities.”

45. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Seventh Canto, 7.3.24 purport, p. 152.

46. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Bhagavad-Gita As It Is (Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1989) 2.31 purport, p. 117.

47. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: First Canto, 1.2.13 purport, p. 108.

48. Ibid., 1.5.24 purport, p. 272.

49. Ibid., 1.16.31 purport, p. 935.

50. Ibid., 1.8.5 purport, p. 403.

51. Ibid., 1.13.24 purport, p. 739.

52. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Bhagavad-Gita As It Is, 1.40 purport, p. 67.

53. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Second Canto, 2.6.20 purport, p. 313.

54. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Fourth Canto, 4.16.10 purport, 1:725.

55. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: First Canto, 1.2.2 purport, p. 89.

56. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Tenth Canto, 10.8.6 purport, p. 436.

57. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Bhagavad-Gita As It Is, 1.40 purport, p. 66.

58. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Third Canto, 3.22.4 purport, 2:206.

59. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Fourth Canto, 4.20.28 purport, 2:44.

60. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Fifth Canto, 5.13.8 purport, p. 438.

61. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: First Canto, 1.5.24 purport, p. 272.

62. Ibid., 1.11.36 purport, p. 641.

63. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Sixth Canto, 6.3.13 purport, p. 154.

64. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: First Canto, 1.15.39 purport, p. 880.

65. Ibid., 1.5.24 purport, p. 272.

66. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Third Canto, 3.21.52 purport, vol. 2, p. 198.

67. The Journey of Self-Discovery 7.1, The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, record 316824.

68. Ibid., Lecture: Srimad Bhagavatam 2.3.1, Los Angeles, 19 May 1972, record 349873.

69. Ibid, Initiation Lecture Excerpt, London, 7 September 1971, record 374193.

70. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Sixth Canto, 6.5.39 purport, p. 310.

71. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Ninth Canto, 9.2.23-24 purport, p. 48.

72. Morning Walk, “Varnashrama College,” Vrindavan, 14 March 1974, The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, record 426878.

73. Ibid., Letter to: Prabhakar, Honolulu, 31 May 1975, record 604402.

74. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Fourth Canto, 4.12.10 purport, 1:555.

75. Morning Walk, “Varnashrama College,” Vrindavan, 14 March 1974, The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, record 426806.

76. Ibid., record 426856.

77. Ibid., record 426912.

78. Ibid., record 426916.

79. Ibid., Lecture: Bhagavad-gita 1.28-29, London, 22 July 1973, record 321203.

80. Ibid., Lecture: Bhagavad-gita 2.36-37, London, 4 September 1973, record 324206.

81. Ibid., Lecture: Srimad-Bhagavatam 1.7.28-29, Vrindavan, 25 September 1976, record 344572.

82. Ibid., Lecture: Srimad-Bhagavatam 2.3.17, Los Angeles, 12 July 1969, record 350225.

83. Ibid., Lecture: Bhagavad-gita 1.28.29, London, 22 July 1973, record 321203.

84. Ibid., Room Conversation, Indore, 13 December 1970, record 396710.

85. Ibid., Morning Conversation, Bombay, 11 April 1977, record 552458.

86. Ibid., Morning Conversation, Vrindavan, 23 June 1977, recording 561228.

87. Ibid., Lecture: Bhagavad-gita 1.31, London, 24 July 1973, record 321250.

88. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Fourth Canto, 4.13.19-20 purport, p. 626.

89. Ibid., 4.21.6 purport, 2:63.

90. Ibid., 4.22.45 purport, 2:212.

91. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Sixth Canto, 6.4.11 purport, p. 200.

92. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Ninth Canto, 9.13.12 purport, p. 425.

93. Lecture: Bhagavad-gita 1.4, London, 10 July 1973, The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, Sandy Ridge 1995, record 320926.

94. Ibid., Room Conversation, Bombay, 21 August 1975, record 467143.

95. Ibid., Letter to: Dr. Wolf, Honolulu, 20 May 1976, record 607891.

96. Ibid., Room Conversation, Toronto, 17 June 1976, record 499762.

97. Ibid., Morning Walk, Bombay, 20 November 1975, records 476348-476350.

98. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Fourth Canto, 4.25.10 purport, p. 435.

99. Conversation During Massage, Bhubaneswar, 23 January 1977, The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, records 540250-540252.

100. Ibid., Morning Walk, “Varnashrama College,” Vrindavan, 14 March 1974, record 426808.

101. Ibid., record 521531.

102. Ibid., Conversation with Seven Ministers of Andhra Pradesh, Hyderabad, 22 August 1976, record 521531.

103. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Fourth Canto, 4.12.10 purport, 1:555.

104. Bhaktivedanta Swami never referred to his followers and supporters as a “congregation”: “we are not a church. It is true that our congregation is not increasing, simply the inmates are becoming more numerous. We should be classified as a residential temple. . . . We simply have a bigger family therefore our temple is bigger.” Letter to: Karandhara, Auckland, 21 February 1973, The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, record 598178.

105. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Third Canto, 3.21.31 purport, 2:178.

106. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, The Science of Self-Realization (Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1978), ch. 6, 205.

107. Lecture Excerpt, Montreal, 27 July 1968, The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, record 375748.

108. Ibid., Lecture, Seattle, 7 October 1968, record 376098.

109. Ibid., Morning Walk, “Varnashrama College,” Vrindavan, 14 March 1974, records 426818-426828.

110. Ibid., Lecture: Srimad-Bhagavatam 3.1.10, Dallas, 21 May 1973, record 351445.

111. All statements compiled from public lectures given by Bhaktivedanta Swami between 1966 and 1976: The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, records 325375, 321872, 324287, 373118, 373748, 376098, 348074, 321762, 346644, 364869, 373118, 341145, 321762, 349874, 342416, 352085, 327836, 343560, 343561, 345037, 440043, 359218, 451445, 359947.

112. Ibid., Discussions with Shyamasundara Das: John Dewey, record 383864.

113. Ibid., Room Conversation, Mauritius, 5 October 1975, record 470657.

114. Ibid., Lecture: Srimad-Bhagavatam 1.16.4, Los Angeles, 1 January 1974, record 348074.

115. Ibid., Srimad-Bhagavatam: Second Part (From Seventh Chapter and half to Twelfth Chapter of the First Canto, Delhi 1964), Pre-1965 Writings of Srila Prabhupada, 1.11.36 purport, record 5739. Bhaktivedanta Swami’s editorial team later edited the reference to “negroes” out of this passage. In the 1987 Bhaktivedanta Book Trust edition it reads: “Cupid’s provocations are going on, even among beastly societies who are all ugly-looking in the estimation of the civilized nations” (p. 642).

116. Ibid., Room Conversation, “Varnashrama System Must Be Introduced,” Mayapura, 14 February 1977, The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, record 543832.

117. Ibid., Morning Walk at Villa Borghese, Rome, 26 May 1974, record 435756.

118. Ibid., Lecture: Srimad-Bhagavatam 1.16.8, Los Angeles, 5 January 1974, record 435176.

119. Ibid., Morning Walk, “Varnashrama College,” Vrindavan, 14 March 1974, record 426904.

120. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Fourth Canto, 4.16.4 purport, 1:718

121. Srimad-Bhagavatam 1.7.25, Vrindavan, 22 September 1976, The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, record 344514.

122. Ibid., Morning Walk, Vrindavan, 12 March 1974, record 426651.

123. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Bhagavad-Gita As It Is, 6.13-14 purport, p. 322.

124. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: First Canto, 1.5.24 purport, p. 272.

125. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, The Nectar of Instruction (Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1975), purport, p. 7.

126. Letter to: Tulsi, Mayapur, 12 October 1974, The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, record 602204.

127. Ibid., Letter to: Satsvarupa, Delhi, 25 November 1971, record 594508.

128. Ibid., Letter to: Satyabhama, Hyderabad, 23 March 1973, records 598314-598315.

129. Ibid., Letter to: Krishna Das, Dallas, 9 September 1972, record 597098.

130. Ibid., Letter to: Jayatirtha, 76-01-20, record 606815.

131. Ibid., Lecture: Srimad-Bhagavatam 7.6.1, San Francisco, 6 March 1967, record 361415.

132. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, Srimad Bhagavatam: Fourth Canto, 4.12.23 purport, 1:573.

133. Ibid., 4.12.34 purport, p. 587.

134. Lecture: London, 12 July 1972, The Bhaktivedanta VedaBase CD-ROM, record 379028.

135. Ibid., Letter to: Parent, Mayapur, 4 March 1976, records 607395-607396.

136. Ibid., Room Conversation, Paris, 31 July 1976, record 514761.

137. Ibid., record 514762.